| Why On Earth Do They Call

It Throwing?

An investigation into the origin of words, by Dennis Krueger

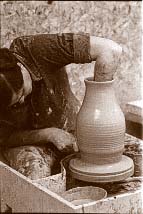

Images courtesy Edouard Bastarache.

When

a person changes professions one carries the knowledge and experience

of the profession left behind into the new profession. In my case

the old profession was German language and literature; the new one,

pottery. I knew that language, like any other attribute of man,

is in a constant state of flux. Anyone who tries to read Chaucer,

or even Shakespeare, in its original form can see the enormous changes

that have occurred in English just since the Middle Ages. I knew

that language has a history just as political events or personalities

do, and I knew that most European languages can be traced back to

Indo-European roots that actually predate writing. When

a person changes professions one carries the knowledge and experience

of the profession left behind into the new profession. In my case

the old profession was German language and literature; the new one,

pottery. I knew that language, like any other attribute of man,

is in a constant state of flux. Anyone who tries to read Chaucer,

or even Shakespeare, in its original form can see the enormous changes

that have occurred in English just since the Middle Ages. I knew

that language has a history just as political events or personalities

do, and I knew that most European languages can be traced back to

Indo-European roots that actually predate writing.

When I first began making pots, I was naturally curious about the

new words I was learning - words which didn't seem to make much

sense. Until then, I had thought grog was a rum drink, slip was

something 'twixt the cup and the lip, and I wondered why on earth

wheel work was called throwing. Since I had the skills in etymology

to answer these questions myself, I eventually got around to doing

just that.

One

of my initial discoveries was of great personal interest. In graduate

school, I had been told by one of my professors that Krueger means

country innkeeper. Krug (not Stein) is the German word for beer

mug and a Krueger is the man who serves beer mugs. This is indeed

one definition. The other is that a Krueger is the man who makes

beer mugs: Krueger means potter. No wonder I had such an affinity

for clay! When I finally explored a larger number of potter's words,

some patterns began to emerge. Within the flux of language some

areas change rapidly and some resist change. Much of the specialized

vocabulary of pottery has resisted change for the simple reason

that the activities and objects described have changed so little

over the centuries. One

of my initial discoveries was of great personal interest. In graduate

school, I had been told by one of my professors that Krueger means

country innkeeper. Krug (not Stein) is the German word for beer

mug and a Krueger is the man who serves beer mugs. This is indeed

one definition. The other is that a Krueger is the man who makes

beer mugs: Krueger means potter. No wonder I had such an affinity

for clay! When I finally explored a larger number of potter's words,

some patterns began to emerge. Within the flux of language some

areas change rapidly and some resist change. Much of the specialized

vocabulary of pottery has resisted change for the simple reason

that the activities and objects described have changed so little

over the centuries.

I shall begin with the words that appear in Old English (500-1050

A.D.), although many have even older roots.

Clay appears in Old English as claeg and means exactly the same

thing it does today. To find the root for clay, we have to go back

to the Indo-European root *glei- meaning to glue, paste, stick together.

To

throw. Potters at Marshall Pottery in Texas describe their work

at the potters wheel as turning. They understand only the modern

meaning of to throw and do not use it to describe their work. However,

the Old English word thrawan from which to throw comes, means to

twist or turn. Going back even farther, the Indo-European root *ter-

means to rub, rub by twisting, twist, turn. The German word drehen,

a direct relative of to throw, means turn and is used in German

for throwing. Because the activity of forming pots on the wheel

has not changed since Old English times, the word throw has retained

its original meaning in the language of pottery but has developed

a completely different meaning in everyday usage. Those who say

they throw pots are using the historically correct term. Those who

say they turn pots are using more current language. Both are saying

the same thing. To

throw. Potters at Marshall Pottery in Texas describe their work

at the potters wheel as turning. They understand only the modern

meaning of to throw and do not use it to describe their work. However,

the Old English word thrawan from which to throw comes, means to

twist or turn. Going back even farther, the Indo-European root *ter-

means to rub, rub by twisting, twist, turn. The German word drehen,

a direct relative of to throw, means turn and is used in German

for throwing. Because the activity of forming pots on the wheel

has not changed since Old English times, the word throw has retained

its original meaning in the language of pottery but has developed

a completely different meaning in everyday usage. Those who say

they throw pots are using the historically correct term. Those who

say they turn pots are using more current language. Both are saying

the same thing.

Glaze and glass come from the same root - the Old English root

glaer, meaning amber. Amber, as everyone knows, is a "pale

yellow, sometimes reddish or brownish, fossil resin of vegetable

origin, translucent, brittle." (The Random House Dictionary

of the English Language, 1967). For the English-speaking world,

glass - and with it glaze - must have come into use at a time when

amber was a commonly recognized substance. Since amber was a substance

much like glass in appearance, the word for amber - glaer - was

transferred to the new substance.

Kiln derives from the Latin word culina, meaning kitchen or cookstove.

Culina was introduced to England by the Romans in the first and

second centuries A.D., managed to survive the Anglo-Saxon invasion

of the fifth and sixth centuries, and showed up in the Old English

forms cylene or cyline, meaning large oven. Culina has retained

this specialized meaning ever since, and nowhere is it used to denote

kitchen. Its cousin, culinary, is of much more recent origin. Its

first written appearance was in 1638, and its closeness to the classical

Latin form indicates that it was reintroduced to English by sixteenth

century humanists.

Slip

has a history like that of to throw. It derives from the Old English

word slype, a relative of slop, and its original meaning is liquid

mud. Common usage retains a hint of this meaning in the verb to

slip, and in the common adjective slippery. As a noun, however,

slip means liquid mud only to potters and ceramists. Everyday language

has completely lost the meaning of slip as it is used in pottery. Slip

has a history like that of to throw. It derives from the Old English

word slype, a relative of slop, and its original meaning is liquid

mud. Common usage retains a hint of this meaning in the verb to

slip, and in the common adjective slippery. As a noun, however,

slip means liquid mud only to potters and ceramists. Everyday language

has completely lost the meaning of slip as it is used in pottery.

Pot, potter, pottery. These words do not show up in England until

late Old English or early Middle English (1050-1450). There are

forms of the word pot in Old Frisian, Middle Dutch, Middle Low German,

Old Norse, Swedish, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. However, no

forms exist in Old High German or Middle High German. This suggests

that the word pot comes from some vulgar Latin derivative of the

classical Latin verb potare, to drink. Medieval Latin uses pottus

for drinking cup; classical Latin uses potorium for drinking cup;

and classical Greek uses poterion for drinking cup. The Oxford English

Dictionary, however, disputes this etymology and claims that the

origin of pot is unknown. Since the former explanation is better

than no explanation, I shall opt for it. Pot comes eventually from

the Latin word for drinking cup. It seems likely that the words

pot and potter were introduced to England at the time of the Norman

conquest (1066). Pottery seems to be a much later addition to English

than pot or potter. Apparently it was adopted from the French poterie

in the fifteenth century. By the way, the -er of potter means one

who makes, and the -ery means the place where.

Since

pot, potter, and pottery come into English relatively late, it is

logical to assume that they displaced another set of words prior

to their arrival. After casting about for a number of possibilities,

I hit upon crock, crocker, and crockery, and decided to see how

old they are. Crock goes back to Old English crocc - crocca meaning

earthenware pot or pitcher - and is related to Icelandic krukka,

Danish krukke, Swedish kruka, Old High German krog or kruog, Middle

High German kruoc, and German krug! The ultimate origin of crock

is unknown. There is a written record of the word crock, dating

from about 1000 A.D. Crocker is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary

as "potter." The earliest written record of crocker occurs

around 1315. The existence of Crocker today as a surname is strong

evidence that it is quite old. Crockery is defined by the Oxford

English Dictionary as "crocks, or earthenware vessels, collectively

earthenware, especially domestic utensils of earthenware."

Its earliest written appearance was in 1755. This suggests to me

that until the arrival of the Normans in 1066, crock and crocker

were the common Anglo-Saxon terms for pot and potter which were

pushed aside by the new terms imported by the French-speaking Normans

in 1066, but which lived on with a specialized meaning. Crockery,

however, seems to be a much later coinage, probably formed by analogy

to other nouns ending in -ery. Crockery did not come into common

use until the eighteenth century. Since

pot, potter, and pottery come into English relatively late, it is

logical to assume that they displaced another set of words prior

to their arrival. After casting about for a number of possibilities,

I hit upon crock, crocker, and crockery, and decided to see how

old they are. Crock goes back to Old English crocc - crocca meaning

earthenware pot or pitcher - and is related to Icelandic krukka,

Danish krukke, Swedish kruka, Old High German krog or kruog, Middle

High German kruoc, and German krug! The ultimate origin of crock

is unknown. There is a written record of the word crock, dating

from about 1000 A.D. Crocker is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary

as "potter." The earliest written record of crocker occurs

around 1315. The existence of Crocker today as a surname is strong

evidence that it is quite old. Crockery is defined by the Oxford

English Dictionary as "crocks, or earthenware vessels, collectively

earthenware, especially domestic utensils of earthenware."

Its earliest written appearance was in 1755. This suggests to me

that until the arrival of the Normans in 1066, crock and crocker

were the common Anglo-Saxon terms for pot and potter which were

pushed aside by the new terms imported by the French-speaking Normans

in 1066, but which lived on with a specialized meaning. Crockery,

however, seems to be a much later coinage, probably formed by analogy

to other nouns ending in -ery. Crockery did not come into common

use until the eighteenth century.

Four words whose origins are unknown, but which are probably quite

old, are to wedge, bat, grog, and saggar. Their monosyllabic forms

would seem to indicate Anglo-Saxon roots, but no evidence exists

to prove that one way or the other. Even the Oxford English Dictionary

sheds no light on their derivation.

To wedge. The Oxford English Dictionary contains the following

under to wedge:

wedge,

v. in 7 wage (of obscure origin; the modern form is probably less

correct than the earlier wage but cf wedge Sb 4). Trans. to cut

(wet clay) into masses and work them by kneading and throwing down,

in order to expel air bubbles. 1686 Plot. Staffordish. 123 (Potter's

clay) is brought to the waging board, where it is slit into flat,

thin pieces . . . This being done, they wage it, i.e., knead or

mould it like bread. wedge,

v. in 7 wage (of obscure origin; the modern form is probably less

correct than the earlier wage but cf wedge Sb 4). Trans. to cut

(wet clay) into masses and work them by kneading and throwing down,

in order to expel air bubbles. 1686 Plot. Staffordish. 123 (Potter's

clay) is brought to the waging board, where it is slit into flat,

thin pieces . . . This being done, they wage it, i.e., knead or

mould it like bread.

The latter part of this entry contains the date, 1686, of the oldest

written record of the word. I suspect that the word is much older

and that if it is related to wage, it may simply mean something

like make, as in the expression "to wage war," but that

is just speculation on my part.

Bat. On bat there is even less information than on wedge. The Oxford

English Dictionary defines bat as a "lump, a piece of certain

substances" and calls its origin obscure.

Grog. As used by potters, grog must be a figment of our imaginations

because it is not listed in any of the major dictionaries I consulted.

(It is found in An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics.) The Oxford

English Dictionary lists only the meaning for the rum drink. Perhaps

if potters who read this would send sharp letters of protest to

the editors of Random House, Oxford English, and other dictionaries,

this deplorable situation could be corrected.

Saggar. Saggar seems to be a corruption of safeguard.

Many

words are derived from the names of the places they are found, or

from the way they are made or used. Ball clay is a type of clay

found in Dorset and Devon in England, so named because the clay

was cut into balls weighing about thirty pounds. Bentonite is named

after Fort Benton, Montana, where it was first mined. China is named

after the country of its origin. Kaolin is of Chinese origin and

derives from kao ling, meaning high hill - the place it was first

found. Faience, the tin-glazed earthenware, was made at Faenza,

Italy, in the sixteenth century. maiolica is named after the island

of Majorca (formerly maiolica), which was a transfer point for work

produced in Valencia, Spain, and exported to Italy. Mishima may

derive from the radiating character of certain almanacs made at

Mishima, Japan, or it may have been acquired by association with

the island of Mishima where the ware was transshipped from Korea.

Potash - potassium carbonate - was originally produced by burning

wood in a pot. The Dutch coined the term potasch in 1598, and it

entered English in 1648. Raku means enjoyment, and the ware takes

its name from a seal engraved with this word, which was used to

mark early pieces. It is also the name of a series of potters -

Raku I-XIV. Many

words are derived from the names of the places they are found, or

from the way they are made or used. Ball clay is a type of clay

found in Dorset and Devon in England, so named because the clay

was cut into balls weighing about thirty pounds. Bentonite is named

after Fort Benton, Montana, where it was first mined. China is named

after the country of its origin. Kaolin is of Chinese origin and

derives from kao ling, meaning high hill - the place it was first

found. Faience, the tin-glazed earthenware, was made at Faenza,

Italy, in the sixteenth century. maiolica is named after the island

of Majorca (formerly maiolica), which was a transfer point for work

produced in Valencia, Spain, and exported to Italy. Mishima may

derive from the radiating character of certain almanacs made at

Mishima, Japan, or it may have been acquired by association with

the island of Mishima where the ware was transshipped from Korea.

Potash - potassium carbonate - was originally produced by burning

wood in a pot. The Dutch coined the term potasch in 1598, and it

entered English in 1648. Raku means enjoyment, and the ware takes

its name from a seal engraved with this word, which was used to

mark early pieces. It is also the name of a series of potters -

Raku I-XIV.

The derivations of some words that came into the language in the

Middle English period (1050-1450), or later, are quite amusing.

Porcelain. Chinese porcelain was reputedly first introduced to

Europe by Marco Polo via Italy. The Italians therefore had the privilege

of giving it a European name (although some say it was the Portuguese

who named it). They called it porcellana. In French it became porcelaine.

The English took it over from the French and dropped the final -e.

The Italians probably kept the origin of the word a secret; it is

unlikely that the English would have had anything to do with it

otherwise. Italian porcellana originally denoted the sea shell concha

veneris. This Venus' conch shell is hard and white, and perhaps

the Italians named the Chinese ware porcellana because they thought

the shell was ground up and used in the body, or because of the

similarity in hardness and whiteness. More interestingly, the word

for the seashell itself comes from the word porca, pork. The shell

was so named because of its similarity to the genitalia of the sow.

Celadon

is an equally interesting word. Most of the dictionaries say that

the name comes from the character Celadon in Honore d'Urfe's novel

Astree. d'Urfe for his part is said to have borrowed the name from

the Latin poet Ovid. The character in d'Urfe's novel always wore

pale green ribbons. The connection seems tenuous at best, and no

one can explain how the name was transferred to a pale green Chinese

glaze. An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics offers this much more

likely derivation: "The name is probably a corruption of Salah-ed-din

(Saladin), Sultan of Egypt, who sent forty pieces of this ware to

Nur-ed-din, Sultan of Damascus, in 1171." Celadon

is an equally interesting word. Most of the dictionaries say that

the name comes from the character Celadon in Honore d'Urfe's novel

Astree. d'Urfe for his part is said to have borrowed the name from

the Latin poet Ovid. The character in d'Urfe's novel always wore

pale green ribbons. The connection seems tenuous at best, and no

one can explain how the name was transferred to a pale green Chinese

glaze. An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics offers this much more

likely derivation: "The name is probably a corruption of Salah-ed-din

(Saladin), Sultan of Egypt, who sent forty pieces of this ware to

Nur-ed-din, Sultan of Damascus, in 1171."

Stein. When I was an undergraduate student at the University of

Freiburg in the Black Forest area of West Germany, I remember being

asked by a friend back home to send her a beer mug. I went to a

shop and in my best German (which at the time was none too good)

I asked for a Bierstein. The saleswoman kept asking me to speak

English. I kept refusing because I was determined to speak only

German. She only figured out what I wanted when I pointed to the

object. Later, I realized that Bierkrug is the correct word, and

that Stein means stone. How the German word for stone has come to

mean mug in America is a mystery to me. I still feel embarrassment

for not having known the difference that day in Freiburg.

Direct

borrowings from other languages are common in the English language

for pottery. We have already seen kaolin, mishima, and raku. Some

others are ceramics, engobe, sgraffito, and temmoku. Ceramic is

of recent French origin. It was borrowed from ceramique in the nineteenth

century. Its root is the Greek word keram(os), potter's clay. Engobe

derives from the French en- plus gober which means, literally, to

gulp, take in the mouth, hence to coat something with saliva. From

this original meaning to its current sense is not too great a leap.

Its earliest appearance in written English was in 1857 in Birch's

Ancient Pottery. Sgraffito is borrowed from Italian and derives

ultimately from the Greek graphein, to write or scratch. Temmoku

is used to describe black-glazed stoneware cups and bowls made during

the Sung dynasty (960-1280) at Chien-an (Honan province), China,

and so called by the Japanese who sought the ware for use in the

tea ceremony. I do not know its meaning or origin. Direct

borrowings from other languages are common in the English language

for pottery. We have already seen kaolin, mishima, and raku. Some

others are ceramics, engobe, sgraffito, and temmoku. Ceramic is

of recent French origin. It was borrowed from ceramique in the nineteenth

century. Its root is the Greek word keram(os), potter's clay. Engobe

derives from the French en- plus gober which means, literally, to

gulp, take in the mouth, hence to coat something with saliva. From

this original meaning to its current sense is not too great a leap.

Its earliest appearance in written English was in 1857 in Birch's

Ancient Pottery. Sgraffito is borrowed from Italian and derives

ultimately from the Greek graphein, to write or scratch. Temmoku

is used to describe black-glazed stoneware cups and bowls made during

the Sung dynasty (960-1280) at Chien-an (Honan province), China,

and so called by the Japanese who sought the ware for use in the

tea ceremony. I do not know its meaning or origin.

Modern technology has introduced a number of new words to the language

of pottery. Opax, superpax, and zircopax are all based on opacifier.

Fiberfrax is from fiber and refractory, kaowool from kaolin and

wool. While these are brand names, they are often also used as common

names.

Finally,

I decided to see where art and craft would lead me. Art goes back

to the Indo-European root *ar-, to join. Craft derives from the

Indo-European root *ger-, to twist, turn. I was tempted to try to

make something out of the difference but gave up the idea, knowing

that it would be futile. Finally,

I decided to see where art and craft would lead me. Art goes back

to the Indo-European root *ar-, to join. Craft derives from the

Indo-European root *ger-, to twist, turn. I was tempted to try to

make something out of the difference but gave up the idea, knowing

that it would be futile.

In summary, the potter's language has a core of words that go back

to Old English roots, and beyond, which have changed little in form

or meaning over the centuries because the objects and activities

have changed little. Many new words have been added - largely from

foreign sources - describing new techniques, new bodies, new technology,

or new objects so that there is a continuous enlargement of the

core vocabulary: a sign of a healthy and vigorous craft.

More Articles

|