| Interview

with Koie Ryoji

by Yokoya Hideko, translation Nishi Keiko

Originally published in Robert Yellin's Japanese

Pottery Information Center on

e-yakimono.net. Reprinted by permission.

Akaska Inui Gallery, Minato-ku,

Tokyo, June 21, 2002

Koie Ryoji

INTRODUCTION

"Go ahead, ask me anything you want," he said. His

loud and bright voice struck me and the whole room brightened up.

This man in front of me, with the cheerful smile on his sun-tanned

face, this is the pottery master-star, Mr. Koie Ryoji. "Ha,

ha, ha, good, good, and?" he says with warmth, making me feel

at ease. It turns out he was doing all this to help me loosen up

and relax a bit.

In the world of practical pottery (e.g., chawan, tsubo, plates),

Koie Ryoji has developed his own realm, beyond any prejudiced concept

of pottery or what it means. In the world of modern art, moreover,

he has been sending important messages to society through other

artistic endeavors, such as his "Returning to Clay" series.

Koie takes pleasure in freely exploring the two realms. With a flexible

attitude and a power beyond national borders -- which does not allow

him to stay in one place very long -- people cannot help being attracted

to him.

Yes, now I get it! I know that's the reason why young wannabe-potters,

not only Japanese, but also from other countries, gather around

him; the reason why many potters make Koie-like works unintentionally.

I understand the reasons so well now.

Impressive Large Plate

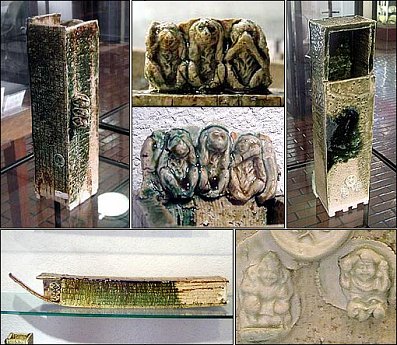

Series entitled Mizaru, Iwazaru, Kikazaru

(see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil); background is NY 9.11

Exuding

an Interest in Living

Koie has exhibitions one after another. But, exhibitions

are not the only thing that keeps him busy.

Y: Koie Sensei !

K: YES!

Y: You are so well tanned.

K: I went to Hokkaido to make a monument and I worked outside

all the time for more then ten days.

Y: What kind of monument?

K:

I dug a long groove -- about 10 centimeters wide in the ground,

swiftly poured in liquid aluminum, and set an aluminum column in

the groove standing up. K:

I dug a long groove -- about 10 centimeters wide in the ground,

swiftly poured in liquid aluminum, and set an aluminum column in

the groove standing up.

Y: So, it isn't yakimono, is it?

K: Well, it is yakimono. The aluminum was about 700 degrees

centigrade, so the ground got burned. Therefore, it was yakimono.

It is just a standing column, but it left a scorch mark on the ground.

That's like "Scar Art."

Y: Sounds very poetic. Where is it?

K: Atsuta-mura (village). It is a small village with a population

of 3,000, located north of Ishikari city. Nice place it is. It's

by the Japan Sea, so a lot of driftage shows up from Russia and

Korea. Looking at all that stuff is interesting! I'm the type of

guy who finds anything interesting.

Y: But still, doing that at such a busy time, with all your

exhibitions.

K: I am crazily busy. As such, I am happy and thankful. I

don't mind being so busy as being too fragile to be broken.

Y: When do you sleep?

K: Well, I sleep when I'm sleepy, and I drink when I want

to. Those times are what I call my sleeping hours. I used to sleep

three times a day. You know, I don't work without drinking. So I

do my job while drinking, and when I get tired from drinking too

much, I go to bed. Then, when I wake up, I start drinking and working.

I kept repeating that. In that respect, I felt like I lived three

times more than a regular person. I used to work that much. I don't

work as hard these days, but I think it's ok anyway. As a result,

my sleeping hours are totally messed up. There are people who have

decided to sleep six to eight hours. But, I believe it doesn't have

to be decided. In the last firing, I fired for 11 days continuously,

so I hardly slept. "What is being awake?" I sometimes

wonder. I know people who are awake yet sleeping. I sometimes find

a guy eyes-open who must be sleeping for Christsake. Then, there

are people who are sleeping, while being awake, who are all ears.

Y: Ummm, one can never be too careful.

K: Yeah, yeah. Yet, I don't want to be obsessed with prejudices

or something. Once you are stuck with prejudices, it's over. It's

no fun just to live. You have to experience the fun of living.

New

York and September 11th

Koie works in a huge variety of styles -- white works, hikidashi-guro

(black), sometsuke (overglazed porcelain), yakishime and more. I'll

focus on his green works, like his Oribe.

They are all green, yet have different personalities.

They dance and play. These chawan are alive.

Y:

I would like to introduce Koie's works as recently exhibited at

the Akasaka Inui Gallery, where this interview took place. Wait,

I have to mention this before continuing -- his newly built anagama

(single-chamber kiln) in his hometown of Okujo Amagasa (in Tokoname,

Aichi), made the news because of its size, 20 meters in length.

It's called the Muteppo-gama, or Temerity Kiln. It was intentionally

made to fire ceramics uneven. That is very Koie-ish, what one might

expect from this artist. Since I had just recently seen another

Koie exhibition, one displaying big tsubo made at that kiln (I vividly

remember some brownish tsubo), I was expecting similar works at

the current exhibit, especially in light of the interest sparked

by the Muteppo-gama. Yet, the space looked like this:

Betraying my expectation of finding brownish works,

the space was filled with green. Betraying my expectation of

seeing round shapes, it was full of edgy and linear works.

Y:

I expected that you would go with brown works.

K: I knew it. It is my job to betray people's expectations.

Almost all my clients look forward to seeing "How is he going

to betray us this time." When one thinks, "Koie must go

like this," they find totally different things.

Y: I see green linear yakimono standing side by side. What

is that expressing? I first thought it was something like a forest,

but the more I look, it begins looking like Manhattan.

K: It is Manhattan! You are right!

Y: Is it? Bingo?

K: Bingo! September 11th was the source. Wow, you got it!

|

|

| Koie's

depiction of the group of buildings in Manhattan

where the terrorist attacks took place. His deep

green copper glaze falls on the unspeaking building.

The title of all these works is "Mizaru,

Iwazaru, Kikazaru." Three Nikko monkeys,

the Mallet of Luck, Daikoku-ten (The God of Wealth

and Farmers), and Ebisu (God of Commerce) can

be seen between the Manhattan buildings standing

side by side. They look like decorative objects

at first glance, but they can be used as vases.

They were fired in a gas kiln. |

|

|

Y:

What is your message in the title, "Mizaru, Iwazaru, Kikazaru?"

K: There are Mizaru, Iwazaru, Kikazaru (see, speak, hear

no evil), but there is no Tsukurazaru, or "make no evil."

Rather than seeing or speaking or hearing unnecessary things, one

should instead be involved in creating. The hidden meaning of the

pieces is that one can do what they want to, instead of only listening

to what someone else is saying.

Y: I can see a Mallet of Luck, Daikoku-ten, and even Ebisu.

Those are all good luck talisman.

K: The rush of business! (laughs)

Y: Making a wish or having one's dream come true?

K: It is all up to how one interprets it. I do not care.

Y: Is this green glaze Oribe?

K: It's better to think of it as a copper glaze. People call

this an Oribe glaze, but one can think more simply, more loosely.

Copper glazes include green glaze, shinsha (red) glaze, kinyo (grayish)

glaze, etc. Copper is the uniform material for all those glazes,

so you can include everything and think of it as "copper glaze."

And among Oribe, there are many kinds, like kuro (black) Oribe,

aka (red) Oribe, and Shino Oribe. Thus, if you stop referring to

Oribe so simply, some would say, "You know about this very

well. What a smart person you are!" (laughs)

Y: I will start using the word "copper glaze" from

now on! And now, looking at this piece (photo below), what is this

reddish thing?

K:

The bases of the marks are shells. Those spots turn out red because

the shells contain salts. This technique has been used since very

old times. Ancient people were very flexible in their ways of thinking

and they took risks. As civilization progressed and living got more

convenient, people started thinking in narrower ways. People have

become shabby.

Y: The horrible terrorist attacks of September 11 in New

York changed the whole world. Why did you choose this time, a year

after the attacks, to make these pieces?

K: It's not like something was finished yesterday, and I

make something today. I think it's better to make something after

the incident sinks in. I've made series like "No More Hiroshima,

Nagasaki" and "Chernobyl." I do believe those things

should not be created right after the incidents. In between, I have

listened to many kinds of music, seen dances, plays, and fashion

shows, and read books. Creating something for me is like having

those accumulated things blossom.

Y: It requires an aging time.

K: Right, I have to have things ferment within myself.

Y: You are doing workshops all over the world. Where were

you at the time of the attacks?

K: I was in Korea at that time. My American friend from New

Jersey was with me, and he got white-faced and could do no work

at all. I suggested to him, "Hey come to Japan. You can work

with me for a while," because he could not get back to America

for the time being. But it didn't work out. He was so terrified.

That was quite sad.

From the "Mizaru, Iwazaru, Kikazaru" series.

What's left was a mass of rubble. I burst into tears.

In

the 60's In

the 60's

When the World was a Fun Place

Y: As I see your chain of performances, I am reminded of John

Lennon and Yoko Ono. What do you think about them?

K: They're wonderful. So were the Beatles. The long and short

of it is that the 1960s was a most interesting and changeable period.

Students acted like real students and had the energy to change the

world. The same can be said of the world of art. I came out at that

time. After all, a person needs to be broken up, proliferating in

other words, maybe? It is ok to change your mind day after day.

I think that is what makes one a person. It is also very human that

one thinks on the same subject continuously, but it is better to

have many different thoughts. So, if one makes pottery, one has

to do other things (for example, free jazz) as well or it won't

work out.

Y: Talking about jazz, musicians often play ad-lib. The exquisite

feeling radiating from jazz is very similar to your physical rhythm

when you are creating ceramics.

K: I think they are quite similar. I agree with what you

mentioned about ad-lib. I do play piano.

Y: Do you? Piano?

K: Yeah, everybody is surprised because I 'm so good at it.

Everybody lets loose a "ha, ha, ha." This is how I act.

I teach at the university (Aich Prefectural University of Fine Arts

and Music). But, I go to the university on the condition of not

teaching, so I do not teach! There is nothing that someone like

me can teach brilliant students. Yet, they are such turkeys. They

are worried like, "What should I create?" or "How

can I make a hit?" They should be creating something if they

have time to worry. That's what I think.

Overseas

Workshops Overseas

Workshops

Y: You've had workshops in eight different countries so far.

How do you deal with the language problem?

K: Well, as long as we create something, we do not need words.

Our creations stand between the words. So, between "ha"

and "well" is a piece of work. So, I create works without

words, and when I wave my hand, a drink will come without me saying

"Give me a drink."

Y: I wonder how it works so well. (laughs)

K: That's how it is. Yes! (emphatically)

Y: In the workshop, do people show their works to each other

like "this is my way?"

K: Uh-huh. When I went to a restaurant in Israel, the master

of the restaurant was better at the wheel than I. Saying, "Get

out of the way, I'll do it," he made a huge tsubo in seconds.

He used to be a potter. That made the whole thing interesting.

Y: Was he that good?

K: He just had skill. What's more important is what else

is in the work. There is no meaning in just creating something.

There are many handy people around, and just being a handy person

is not good enough. I feel sorry for those skillful people. They

do everything smoothly so therefore they don't convey feelings in

their work.

Y: To finish here, could you give us your words on how to

have more GENKI (vigor) in Japan?

K: I began thinking about what Japan is when I was making

ceramics outside Japan. I want to love this country, but cannot

love it as I'd like to. I don't know how to express it. I want my

work to go beyond borders. We've had enough of being swayed by other

countries. War occurs because there is a country. If there were

no countries, there would be no wars.

Y: I see. You are right.

(All of a sudden, Koie grabbed the tape recorder and began speaking

like a radio announcer.)

K: Well, this is how I am. I appreciate all of your continuous

support. I will talk to all of you face to face. Everybody all over

Japan, please be well. Everybody in the world, be well too.

People present in the gallery burst into laughter.

Koie

Ryoji Profile

1938 Born in Tokoname, Aichi

1957 Graduated from Tokoname High School, Ceramic Art Part

1962 Entered Tokoname Ceramic Art Institute

1963 Won award at Asahi Ceramic Art Exhibition

1972 Won "honors" at the 3rd Vallauris International Ceramic

Biennale

1980 Became a member of the International Academy of Ceramics (IAC)

1992 Became professor at Aich Prefectural Univ. of Fine Arts and

Music

1993 Won award of Japan Ceramic Society

1994 Moved a kiln to Kamiyahagi-cho, Ena-gun, Gifu

2002 Built 20-meter anagama in Amagasa, Okujo, Tokoname City

Creates his artwork at various places and holds many exhibitions

(both individually and with groups).

Related Links

Exhibition

of recent works by Koie Ryoji

Photo tour

Exhibit of award-winning Japanese Ceramists

Who's Who

of Japanese Pottery

More Articles

|