| Sculpting their Dreams

- Ethiopian Artists in Israel

by Sara Hakkert

The legend of the ten lost tribes of ancient Israelites has caught

the imagination of writers and poets during the centuries, finding

them was the quest of many. It came partly true when, during the

last century, small communities of Jewish people that called themselves

Beita

Israel (The House of Israel) were discovered in Ethiopia.

It is believed that their unique identity was preserved because

they lead a tightly knitted social life in secluded areas, tenaciously

clinging to the Jewish religion and to the dream of being redeemed

in the Holy Land. This was accomplished with the establishment of

the state of Israel and their miraculous emigration to Israel in

the early eighties.

The legend of the ten lost tribes of ancient Israelites has caught

the imagination of writers and poets during the centuries, finding

them was the quest of many. It came partly true when, during the

last century, small communities of Jewish people that called themselves

Beita

Israel (The House of Israel) were discovered in Ethiopia.

It is believed that their unique identity was preserved because

they lead a tightly knitted social life in secluded areas, tenaciously

clinging to the Jewish religion and to the dream of being redeemed

in the Holy Land. This was accomplished with the establishment of

the state of Israel and their miraculous emigration to Israel in

the early eighties.

The story of their settlement and integration into the life of

the modern state of Israel, which is still taking its course, is

a complex of success and failure; the story of the ceramic artists

from this ethnic group seems to be different.

Traditionally,

pottery in Ethiopia, linked to crafts in general, was among the

less honorable occupations. It may have had to do with a rigid social

structure or, as anthropologists suggest, it may be linked to magic

and the secret of fire; those who know are feared and kept at a

distance. Never the less, the necessity for household utensils for

daily use in the past centuries, made pottery common among men and

women. Alongside, flourished other sculptural and decorative clay

work. Traditionally,

pottery in Ethiopia, linked to crafts in general, was among the

less honorable occupations. It may have had to do with a rigid social

structure or, as anthropologists suggest, it may be linked to magic

and the secret of fire; those who know are feared and kept at a

distance. Never the less, the necessity for household utensils for

daily use in the past centuries, made pottery common among men and

women. Alongside, flourished other sculptural and decorative clay

work.

Among the Ethiopian immigrants that came from Gundar area and other

central locations, were a few ceramic artists who had already studied

and worked in Ethiopia. Thenat Awaqa, Eli Aman, Mulu Geta, Menachem

Dincau and a few others, are in recent years, capturing the attention

of the public with interesting work. They live in different parts

of Israel, with no or little knowledge of each other, yet their

work shows admirable consistency. Not only does it share distinct

common stylistic features, that are characteristic also of works

done in Ethiopian community centers in Israel, but an emotional

affinity prevails over all.

The figurative aspect and the narrative themes are the most striking

traits of the Ethiopian sculptural work done so far. Small figurines,

measuring about fifteen to twenty cm., are the most common and popular

sculptures. These were produced in Ethiopia, along functional ware,

for sale in the market place to tourists; they continue to attract

attention of this slice of the market till today in Israel.

The

figurines are based on a cylindrical body upon which a large head

is resting. Arms, pipelike, are attached to the body terminating

in incised fingers. Legs and feet are usually not outlined in the

more simplified versions, since the body is covered in a long gown.

Legs, again pipelike, when present, are placed with feet flat on

the ground in a rigid position. Female and male figures are depicted,

differentiation centers on the head and upper part of the body,

i.e., females have large breasts, men have beards. All artists work

with a low firing clay, unglazed but burnished with simple natural

tools. The

figurines are based on a cylindrical body upon which a large head

is resting. Arms, pipelike, are attached to the body terminating

in incised fingers. Legs and feet are usually not outlined in the

more simplified versions, since the body is covered in a long gown.

Legs, again pipelike, when present, are placed with feet flat on

the ground in a rigid position. Female and male figures are depicted,

differentiation centers on the head and upper part of the body,

i.e., females have large breasts, men have beards. All artists work

with a low firing clay, unglazed but burnished with simple natural

tools.

In Thenat Awaqa’s work females have large heads due to the

high coiffeur covered with a handkerchief appropriate to Jewish

married women. Faces are elongated with quite large holes for eyes.

Men have beards and are bareheaded, their hair presented by incised

lines. There is little attention to anatomical precision, body and

features are simplified, some are expressively exaggerated. Incised

lines create a linear decoration to enhance the planar surface.

Thenat

Awaqa, a 34 years old mother of four daughters, lives in Israel

since 1991. She comes from a family of potters in the Gundar area,

she trained in Adis-Abeba where she received a diploma in ceramics.

At present she is working at home, hand building and also working

on the wheel “I like to sculpt my dreams” she points

out in an interview, and this innocent remark gives deep insight

into her spiritual and creative world. Thenat

Awaqa, a 34 years old mother of four daughters, lives in Israel

since 1991. She comes from a family of potters in the Gundar area,

she trained in Adis-Abeba where she received a diploma in ceramics.

At present she is working at home, hand building and also working

on the wheel “I like to sculpt my dreams” she points

out in an interview, and this innocent remark gives deep insight

into her spiritual and creative world.

Thenat, and all the other artists who live now in Israel, continue

to work in the tradition they were trained and practiced in the

past. The works of Thenat, Eli, Mulu, Menachem Dincau and a few

others, although exhibiting individual qualities, are deeply rooted

in the art and culture of African tribal art with emphasis on the

domestic and mundane. The folklore of the native Ethiopian village

is recreated in their art, in an innocuous and a somewhat idealized

way. The women are engaged in household chores; carrying water,

preparing food and tending their children. Men are doing the more

strenuous work of gathering wood or pounding wheat. Families are

gathered around the table eating their meals.

Eli Aman who emigrated to Israel in 1984 completed his craft education

in Israel, he is forty one years old. He already took part in group

exhibitions, had several one man shows and his work is shown at

private galleries. Eli’s figures are more sophisticated, some

are larger reaching up to fifty cm., although this is a technical

limitation due to the size of his kiln. He concentrates on the male

figure which is depicted in a dignified way becoming the elders

of the village, monks and teachers. The figures are more varied

and the modeling more plastic, both body and dress show a pronounced

three dimensional presence. The same goes for Menachem Dinkau who

made some very interesting figures of musicians, pregnant women

and a group compositions of a preacher addressing his flock.

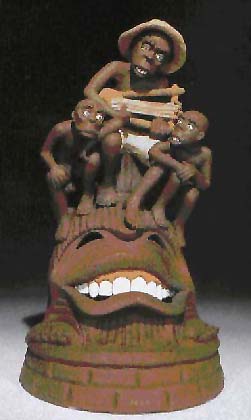

Mulu

Geta (b.1949) studied pottery in Adis-Abeba and also in Israel,

he too is a known figure among the Ethiopian artists. His style

is much more personal, realism and fantasy figure side by side with

a dash of humor. Some of his sculptures deal with the same topics

such as parenthood, but his artistic imagination is given a freer

hand, as in the two small (about 20 cm. high) works titled Family1

and Family2. By joining two almost complete spheres Mulu succeeded,

in these sculptures, to build an expressive human figure despite

its anatomical incongruity, which is also very rewarding, from a

modern, sculptural, point of view. Arms and legs that follow the

abstract decorative pattern on the body are in harmony with the

whole composition. His sense of humor comes out again in the Musician,

a group seated on a grinning frog, or in the Seated Man, a typical

figure of his repertoire but dressed in a western suit and wearing

a ridiculous pair of glasses. Mulu

Geta (b.1949) studied pottery in Adis-Abeba and also in Israel,

he too is a known figure among the Ethiopian artists. His style

is much more personal, realism and fantasy figure side by side with

a dash of humor. Some of his sculptures deal with the same topics

such as parenthood, but his artistic imagination is given a freer

hand, as in the two small (about 20 cm. high) works titled Family1

and Family2. By joining two almost complete spheres Mulu succeeded,

in these sculptures, to build an expressive human figure despite

its anatomical incongruity, which is also very rewarding, from a

modern, sculptural, point of view. Arms and legs that follow the

abstract decorative pattern on the body are in harmony with the

whole composition. His sense of humor comes out again in the Musician,

a group seated on a grinning frog, or in the Seated Man, a typical

figure of his repertoire but dressed in a western suit and wearing

a ridiculous pair of glasses.

The high quality of Mulu’s art is again expressed in the

complicated composition of the Mourning piece. It comprises a group

of people mourning an outstretched dead body on the village background.

In a very tight space he cramped together people and huts with a

multitude of essential details, that created a claustrophobic and

somewhat surreal ambiance befitting the grief experienced. The theme

of death preoccupied Mulu for a long time after his arrival in Israel

being a direct response to the hardship and death that befall the

Ethiopian community during its exodus.

Although

living in Israel for almost two decade during which the artists,

as well as their community at large, came in contact with the local

people, they have somehow remained outsiders. Because of a huge

gap between the Ethiopian way of life in the past, and that found

in modern Israel, a gap which comprises religious, social, economic

and cultural differences, they live in a permanent dilemma. Modern

society exerts a continuous pressure towards assimilation in the

new, strange but alluring culture of the present, a pressure that

clashes with the innate wish to cling to their old traditional way

of life. This conflicting existence pervades their life in general,

and it is striking in their art. They all, as Thenat pointed out,

work from memories which draw upon the same source - the familiar,

beloved, but lost way of life. Although

living in Israel for almost two decade during which the artists,

as well as their community at large, came in contact with the local

people, they have somehow remained outsiders. Because of a huge

gap between the Ethiopian way of life in the past, and that found

in modern Israel, a gap which comprises religious, social, economic

and cultural differences, they live in a permanent dilemma. Modern

society exerts a continuous pressure towards assimilation in the

new, strange but alluring culture of the present, a pressure that

clashes with the innate wish to cling to their old traditional way

of life. This conflicting existence pervades their life in general,

and it is striking in their art. They all, as Thenat pointed out,

work from memories which draw upon the same source - the familiar,

beloved, but lost way of life.

Some inevitable questions arise; for how long can these artists

nourish on memories that tend to fade in time? What will happen

to the distinctive traits of their art that have sprung from a culture

that is not theirs anymore? Will the strong western bearings of

Israel’s modern and sometime abstract art obliterate their

unique innocent vision of the world or their realistic tendencies?

Will they be able, in the future, to sustain the spirit and humanism

of their past work?

Their art, as of present, is certainly in danger. The better artists,

no doubt, will find their own mode of expression, although the outcome

is difficult to predict. Others may continue to produce the same

figurines or bird adorned bowls in a commercialized vein, for which

stagnation already looms. In any case, it seems, the story of the

art of the Ethiopian artists in Israel, is inevitably going to change

in the future. The work done in the recent past should therefore

be much more appreciated and preserved.

Article courtesy of Sara Hakkert.

© Sara Hakkert

More Articles

|