| Roseline Delisle

Article by Penny Smith

Article reprinted with kind permission of Ceramics,

Art & Perception.

My

first encounter with the work of Roseline

Delisle was at the Frank Lloyd Gallery in the Bergamot Station

complex in Santa Monica, LA, where she was one of the artists in

a show entitled Contemporary Ceramics: Nine Artists, held in June,

2000. My

first encounter with the work of Roseline

Delisle was at the Frank Lloyd Gallery in the Bergamot Station

complex in Santa Monica, LA, where she was one of the artists in

a show entitled Contemporary Ceramics: Nine Artists, held in June,

2000.

Delisle’s work immediately impressed me with its sense of

stylised colour and dizzy movement; its balance and precision; the

obvious skills with which she executes her work; her sense of proportion

and scale; her meticulous attention to detail and her neat problem-solving

solutions concerning minimising the real risk of the next ‘big’

earthquake shaker to her pots.

Born in Rimouski, Québec, in Canada, Delisle came from a

creative and art nurturing family environment, with a mother who

worked in clay as a hobby, and a father who sculpted wood part-time.

One of Delisle’s earliest memories was of the sound of her

father’s rhythmic chipping and watching the fine shavings

curling from his chisels. This she often recalls at her wheel in

her own work rhythms as she concentrates on the fine clay curls

that she turns from her finely-honed pieces.

Influenced by an older brother with an interest in science, Delisle

originally thought her future lay in the fields of physics and chemistry,

but a visit to the nearby art school saw her enrolling at the Institute

of the Applied Arts, Montréal, in 1969. In this old style

art school with a strict curriculum of technical learning, her 40

hours of study a week included a wide range of classes that encouraged

the broad use of materials and techniques. However, it was towards

the ceramics studio that she ultimately gravitated.

Once established at her wheel, she started to explore the precise

thrown forms that have become her trademark, at that time in a coarse

stoneware, the colour and consistency of which thwarted her desire

for the finesse that even then she was seeking to achieve. For Delisle

to attempt to throw finely with a coarse stoneware on a kick wheel

says something for the tenacity and wilfulness of this artist in

her pursuit of perfection, and it wasn’t until a friend introduced

her to the seductive stuff of porcelain that she started to make

progress.

After graduating from college in 1973, Delisle travelled to the

Gaspé Peninsula for an apprenticeship with ceramist, Enid

LeGros. In Cree Indian, Gaspé means ‘edge of the world’

which is exactly where Delisle felt she was. In her early 20s, she

was living and working in a cabin in relative isolation, making

finely-thrown and striped porcelain bowls which she was selling

for meagre profit in Montréal.

She eventually found the isolation and the Québecois winters

too hard to take, and was persuaded by friends to go south and join

them in their studio. Making delicately banded and scratched work

and selling them at small local fairs, she says that these were

still her ‘granola days’. Not profiting enough from

her labours, living frugally, with no electricity and no running

water, she left the studio in 1977, in debt. She joined a group

of men friends who were on their way to Alberta to work as lumberjacks,

not knowing what to expect but desperate enough to try anything

to regain solvency.

Delisle learnt how to use a chainsaw, lumber jacking with her male

fellows. As French Canadians – Delisle spoke no English at

this time – the group was given one of the toughest assignments

with the most basic of camps. However, Delisle’s childhood

experience of family summer house building with her father, saw

her shouldering her chainsaw with the best of them and, despite

her slight frame, she endured sub-zero temperatures to make enough,

in a matter of months, to repay her debts and enable her to move

on.

Yearning for warmer climes, Delisle then decided to travel south,

arriving in California in 1978. At this time, she set up her first

studio in Venice, where she established her reputation by having

a number of small studio sales, and catching the eye of such gallery

directors as Garth Clark. She now lives and works in her current

studio in Santa Monica, with husband, the painter, Bruce Cohen,

and their seven year old daughter, Lili.

Both technical and formal concerns have informed and continue to

inform Delisle’s work. Her signature forms have evolved slowly

over many years as a natural process of working in components on

the wheel. Gaining in confidence and skill, she gradually developed

her techniques; inverting and stacking together pieces as a natural

way to achieve larger scale, and increasing their precariousness

by introducing impossible bases. As in her earlier work, decoration

still comprises banding coloured slips (with a little added gum

to harden the colours during handling in kiln packing) on to the

burnished leather-hard pots while they revolve quickly on the wheel.

This she does by eye with pinpoint accuracy and a steady hand, to

achieve the calculated negative spaces between the coloured stripes.

The fired pots are then polished to a fine sheen then coated with

a light mixture of turpentine and melted bees wax. The turpentine,

when it evaporates, leaves behind a fine film of wax that protects

the finished piece.

For many years, since her college days, her vocabulary of form

and colour has been coaxed patiently from her chosen medium of porcelain.

The nature of the medium itself was such that Delisle was so seduced

by its sensuality during the making process that she lived with

the frustrations of the deformities that resulted from the ensuing

high temperature firings. For 25 years she continued the struggle

trying to make her forms defy high temperature kiln gravity, claiming

her stubbornness was due to her endurance of past Canadian winters.

When scale started to become a major philosophical issue, Delisle

reluctantly decided to give up the battle with the material that

she loved and moved to earthenware in order that her work could

move forwards.

In

the exhibition Colour and Fire: Defining Moments in Studio Ceramics,

1950–2000 at the Los Angeles County Museum and Art, Peter

Voulkos states a similar love affair with clay that Delisle feels;

that of having to "feel it in my fingers. Then it gets into

my body, and the invisible becomes visible – sound, movement,

colour, pattern. All these things are coming from my fingertips

like a dancer, I’ve got to be moving, everything comes out

of movement." However, it is Delisle’s latest forms,

her larger scale works (also included in the same show) that really

start to become ‘like a dancer’. In

the exhibition Colour and Fire: Defining Moments in Studio Ceramics,

1950–2000 at the Los Angeles County Museum and Art, Peter

Voulkos states a similar love affair with clay that Delisle feels;

that of having to "feel it in my fingers. Then it gets into

my body, and the invisible becomes visible – sound, movement,

colour, pattern. All these things are coming from my fingertips

like a dancer, I’ve got to be moving, everything comes out

of movement." However, it is Delisle’s latest forms,

her larger scale works (also included in the same show) that really

start to become ‘like a dancer’.

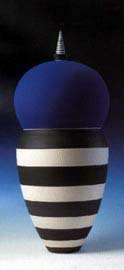

An illustration of Delisle’s transition into movement can

be seen in the works that represent her in the Colour and Fire show;

two earlier pieces, Quadruple 3 (1990), made in porcelain, and 8=1

(1997), made in earthenware, illustrate her development in recent

times. Looking closely at Quadruple 3, one can’t help noticing

the tiny spiral at the top of its blue, black and white striped

lid section, a reminder of the ‘memory’ that the porcelain

had of its throwing; a tiny, defiant ‘unravelling’ of

the form during firing. Minute as this is, the larger frustrations

that this represents in her efforts to manage her materials and

firing procedures in her pursuit for ever more daring dancing forms,

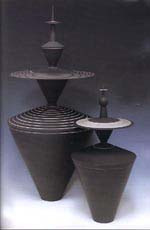

one can understand the switch to earthenware. Just such an example

stands nearby; 8=1 is more than a metre high on its plinth, the

solid black of its body shimmering dully and in stark contrast to

the immaculate lines of white strips on its plate-like top. As one

moves around the piece, the stripes appear to revolve slightly in

the opposite direction in one’s peripheral vision –

a disturbing and intriguing sensation; as unnerving as a Bridget

Riley painting, but a sensation that Delisle would delight in causing.

Having also just seen in the same day an exhibition of the work

of Charles and Ray Eames where, among the universal classics of

pre-formed plywood furniture, was a gem of a film called Tops. One

of the many films made by the pair, Tops featured children (and

grown ups) spinning an enormous variety of different coloured and

shaped tops that they had collected from around the world, to demonstrate

to students the physics of rotational movement. Seeing these whirling

striped forms, and experiencing the disturbance to my equilibrium

with Delisle’s 8=1, it is hardly surprising that Kristine

McKenna should describe Delisle’s work as "evocative

of stylised harlequin figures that threaten to morph into spinning

tops". 1

A particularly appropriate description, given the pivotal moment

Delisle’s future directions took after seeing Oskar Schlemmer’s

reproduction of the 1922 Triadic Ballet in 1979 at the University

of California at Los Angeles, (UCLA Royce Hall). Schlemmer, one

of the many young artists that Walter Gropius employed in the early

days of the Bauhaus, taught drawing and became director of the Bauhaus

stage in Dessau in 1925. The Triadic Ballet was a major choreographic

work that Schlemmer developed, describing it as a "triadic

(from triad – three) because of the three dancers and the

three parts of its symphonic architectonic composition: the fusion

of the dance, the costumes and the music. The special characteristics

of the ballet are the costumes which are of a coloured, three- dimensional

design, the human figure which is an environment of basic mathematical

shapes, and the corresponding movements of that figure in space."

2 Schlemmer’s fellow colleague at the Bauhaus, Wassily Kandinsky,

also worked on commissions for the theatre. In Kandinsky’s

set designs for Mussorgsky’s music, Pictures at an Exhibition,

the inspiration for the figurines in his drawings came from a similarly

mathematical abstraction of the figure, so obvious these days in

Delisle’s work.

The simple boldness of the Kandinsky’s drawings have a similar

dynamic energy to the drawings pinned up in Delisle’s studio.

Her designs, too, are initially mapped out mathematically, cut and

dissected geometric shapes that are reassembled into strong graphic

profiles. These initial drawings she uses as guides to work out

the actual size and shape of the pieces she is to throw, to calculate

how the piece will finally go together. Later, as a relief to the

strictness required of her making techniques, and as a prelude to

the exacting task of decorating, she will return to the drawings,

re-rendering them in energetic expressions of rapid marks that make

them start to shimmer and move.

As

illustrated by the small sketches of Kandinksky’s figures,

the sense of monumentality has little to do with scale. As examples,

witness the jewellery of Wendy Ramshaw, with her fine turned finger

rings in metal and perspex, striped, stacked, spiked and coned on

their personal stands; or the polyester pleated, hooped Tokyo Vogu

frock of Issey Miyake, or a Brancusi sculpture or Skytower, the

central focus to Sydney’s cityscape. Monumentality has more

to do with understanding the relationships between form and space. As

illustrated by the small sketches of Kandinksky’s figures,

the sense of monumentality has little to do with scale. As examples,

witness the jewellery of Wendy Ramshaw, with her fine turned finger

rings in metal and perspex, striped, stacked, spiked and coned on

their personal stands; or the polyester pleated, hooped Tokyo Vogu

frock of Issey Miyake, or a Brancusi sculpture or Skytower, the

central focus to Sydney’s cityscape. Monumentality has more

to do with understanding the relationships between form and space.

Conscious of these as influences on her work, Delisle has achieved

the extremities of form she has demanded of some of her later works

with their increase in scale, by cunning methods of construction,

matched only with her skills to carry them out. For example, the

narrow waists with flaring skirts; the bulbous ‘hips’

and ‘shoulders’ and the tiny bases of her pots are all

thrown in sections. All are scrupulously manufactured to superfine

tolerances, often decorated inside and underneath as well as on

their outer surfaces. Delisle now assembles her forms both at leather-hard

and at post firing stage, as opposed to letting the porcelain parts

fuse together at high temperature. Her damp cupboard is a morgue

to the spare body parts she has left over from previous work sessions,

these she ‘brings out to play’ with the new parts, using

them as an extension of her drawing process.

So precise are her skills at assembling these new totemic works,

that it is difficult to see where each join occurs. She makes no

secret of the fact that they are in sections, each piece is often

named after the number of parts from which they are made. Octet

2, for example, or Septet 1. Each individual part of the piece is

then threaded on metal rods that feed right through the centre of

each section, finally being secured at the base into their own personalised

wooden pedestals that are weighted with sand. This acts as her earthquake

security system.

Since the arrival of Lili to the family, Delisle has come to recognise

that her explorations of scale have become even more connected to

the figure, but within a family group. She has taken to choreographing

her work together in a conscious array of form, size, shape and

colour.

She is starting to explore more fully the inter-relationship of

these forms to each other within space; to the dynamic gaps that

now occur between each form as the stridency of their decoration

and the crispness of their shapes creates an even greater sense

of discourse. She cites Frank Gehry’s Dancing House or (‘Fred

and Ginger’) in Prague as a good example of how humanistic

architectural structures can actually ‘talk to each other’;

how in this building, Gehry has successfully combined the old with

the radically new in an attempt to launch old social structures

into a brave new millennium.

On her studio walls, there are two drawings of significance. One

is by Lili, a faithful rendering of one of her mother’s works,

but Lili’s has a softer, more fluid profile; the other is

by Delisle herself, of a top heavy, asymmetrical, full-bodied ellipse,

topping an elegant tapering base. Delisle’s possible future

directions then, could best be described through Lili’s recent

observations of passing a pregnant woman in the street. As the young

woman’s well rounded belly in her body-hugging dress came

into profile, Lili announced that here was another of her mother’s

pots. A startling revelation into the asymmetry of the human figure

that Delisle says she is not quite ready to explore. In the meantime,

Delisle’s repertoire is full with her current concerns and

her immediate future looks busy.

References:

- Kristine McKenna, Roseline Delisle catalogue,

produced by Frank Lloyd Gallery, June 5 – July 3, 1999.

- Oskar Schlemmer, ‘The Mathematics of Dance’.

Vivos voco (Leipzig) Vol. 5. August-September 1926.

Penny Smith is a ceramic artist from Hobart, Tasmania.

At the time of writing this article, she was residing in Los Angeles

with her husband, John, who was an Australia Council grant recipient

at the 18th Street Arts Complex, Santa Monica. Photography by Anthony

Cuñha. Penny Smith wishes to thank the Frank Lloyd Gallery

for support in writing this article. Roseline Delisle is represented

by the Frank Lloyd Gallery, Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, California,

USA. Article reprinted with kind permission of Ceramics,

Art & Perception. © Penny

Smith

More Articles

More Artists of the Week

|