| Salku

An experimental process. Article by Rick Berman.

Originally published in Clay

Times Magazine.

Ironically, this was the title of my MFA Thesis at the University

of Georgia in 1973. I'll try to explain as simply as possible

where this research has taken me in the last 24 years.

From

the very beginning of my clay life in 1968, I have felt this amazing

affinity for those nasty wood-fired pots from the “Six Ancient

Kilns” of Japan: Shigaraki, Tamba, Echizen, Tokoname, Seto,

and Bizen. The whole idea of a pot being put into a kiln and allowing

it to become nature itself just blows me away! I guess the things

going on in the U.S. in the '60s and early '70s that

were closest to these Japanese pots were what Don Reitz was doing

with salt and Paul Soldner and Howard Shapiro were doing with raku. From

the very beginning of my clay life in 1968, I have felt this amazing

affinity for those nasty wood-fired pots from the “Six Ancient

Kilns” of Japan: Shigaraki, Tamba, Echizen, Tokoname, Seto,

and Bizen. The whole idea of a pot being put into a kiln and allowing

it to become nature itself just blows me away! I guess the things

going on in the U.S. in the '60s and early '70s that

were closest to these Japanese pots were what Don Reitz was doing

with salt and Paul Soldner and Howard Shapiro were doing with raku.

I

was experimenting with both of these techniques in graduate school

and somehow had the idea to combine the two: thus SALKU. I built

a small, hard brick updraft top-loading kiln and fired with a homemade

venturi burner and propane. The pots were stacked not touching and

I used about five pounds of salt (but who's counting?) when

the kiln got to cone 06. Salt will volitalize at cone 06 but obviously

if the clay isn't vitrified, the salt just goes through the

cross section of the pot wall until it “fills up.” The

net result was a slight sheen, but no orange peel surface. I took

the pots out of the kiln hot and smoked them in sawdust. The slight

glaze sheen crazed because of the thermal shock, and a very subtle

white crackle occurred. The key word here is “subtle.”

Now you might say at this point, “What's the point?”–

and that's pretty much what I said, too – but it was

research and I did graduate. I

was experimenting with both of these techniques in graduate school

and somehow had the idea to combine the two: thus SALKU. I built

a small, hard brick updraft top-loading kiln and fired with a homemade

venturi burner and propane. The pots were stacked not touching and

I used about five pounds of salt (but who's counting?) when

the kiln got to cone 06. Salt will volitalize at cone 06 but obviously

if the clay isn't vitrified, the salt just goes through the

cross section of the pot wall until it “fills up.” The

net result was a slight sheen, but no orange peel surface. I took

the pots out of the kiln hot and smoked them in sawdust. The slight

glaze sheen crazed because of the thermal shock, and a very subtle

white crackle occurred. The key word here is “subtle.”

Now you might say at this point, “What's the point?”–

and that's pretty much what I said, too – but it was

research and I did graduate.

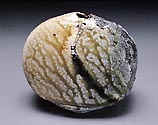

Now

fast forward to 1977 and a workshop at Tennessee State University

in Johnson City. We packed the pots in a soft brick kiln, lit the

burner, set it to what I thought was a slow, even flame, and went

inside to look at slides. After probably an hour and a half or so,

we went back to the kiln to find the most beautiful white heat I've

ever seen...at least cone 8. All I could think to do at this point

was to throw in about ten pounds of salt, let it do its salt thing

for about 20 minutes, and shut it down. We took the top off and

started to unload the pots. It was without a doubt the biggest mess

I've ever seen! Pulling the pots apart was kind of like pulling

taffy—total disaster except for one pot that was in the bottom

middle of the whole mess. To this day, it is probably the most beautiful

pot I've ever seen. It was dry, wet, black, orange, grey,

with beautiful scars and warps. Except for Marvin Tadlock, who made

the pot, and me, people were not amused. (Too bad we live in such

a product oriented society.) Now

fast forward to 1977 and a workshop at Tennessee State University

in Johnson City. We packed the pots in a soft brick kiln, lit the

burner, set it to what I thought was a slow, even flame, and went

inside to look at slides. After probably an hour and a half or so,

we went back to the kiln to find the most beautiful white heat I've

ever seen...at least cone 8. All I could think to do at this point

was to throw in about ten pounds of salt, let it do its salt thing

for about 20 minutes, and shut it down. We took the top off and

started to unload the pots. It was without a doubt the biggest mess

I've ever seen! Pulling the pots apart was kind of like pulling

taffy—total disaster except for one pot that was in the bottom

middle of the whole mess. To this day, it is probably the most beautiful

pot I've ever seen. It was dry, wet, black, orange, grey,

with beautiful scars and warps. Except for Marvin Tadlock, who made

the pot, and me, people were not amused. (Too bad we live in such

a product oriented society.)

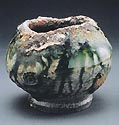

Well,

anyway, fast forward again to 1990 when I was doing a raku workshop

for my dear friend Tom Zwierlein at his studio in the country near

Lexington, Kentucky. On the second day, he asked if I'd like

to try a saggar salt technique he'd been working with. I'm

always up for stealing other people's ideas, so of course

I said yes. He took a saggar (a Lays potato chip can) and went to

work. He lined the bottom of the can with charcoal and vermiculite,

then pots, then salt, then charcoal, then pots, etc. until the can

was full. We put the can in the fiber drum raku kiln, fired it to

1850 F degrees, opened the kiln, took out the saggar, and unloaded

the pots and quenched them in water. Every pot was a killer! Orange,

red, black, grey, white, spots, lines, etc. Well,

anyway, fast forward again to 1990 when I was doing a raku workshop

for my dear friend Tom Zwierlein at his studio in the country near

Lexington, Kentucky. On the second day, he asked if I'd like

to try a saggar salt technique he'd been working with. I'm

always up for stealing other people's ideas, so of course

I said yes. He took a saggar (a Lays potato chip can) and went to

work. He lined the bottom of the can with charcoal and vermiculite,

then pots, then salt, then charcoal, then pots, etc. until the can

was full. We put the can in the fiber drum raku kiln, fired it to

1850 F degrees, opened the kiln, took out the saggar, and unloaded

the pots and quenched them in water. Every pot was a killer! Orange,

red, black, grey, white, spots, lines, etc.

After that, I started using the technique in my workshops and

teaching. Then one day about two years later, a light bulb went

on. SALKU! 1973! Duh. There were some problems at this point.

Number one, the salt was eating up the fiber drums, and if the pots

were fired much below about cone 04, they turned into chia pets

in about two weeks and totally disintegrated. This wasn't

too good for public relations. I felt kind of like a traveling spot

remover salesman who needs to keep moving.

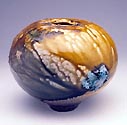

At any rate, I built a small soft brick (scrap) updraft Salku

kiln and corbled in the top with a 5-inch flue. The kiln measured

2-1/2 bricks across and about 15 courses high, roughly six or seven

cubic feet. The whole kiln became a saggar, so we eliminated the

potato chip cans. Now I'm tumble stacking tenmoku and ash-glazed

pots with a half bag of charcoal all through the pots and I'm

firing to approximately cone 10 in four or five hours. I use about

5 lbs. of salt and the pots are getting some beautiful black orange

peel from the melting charcoal, and sometimes stick together so

when they are pulled apart, some dramatic scarification is happening.

Remember those nasty Japanese pots mentioned above? Well, with a

lot of help from nature, I'm seeing surfaces now that I never

thought were possible. Making pots is even more of a joy when you

love the surface possibilities so much that you literally can't

wait to see the next group of pots come out of the kiln. I am very

grateful.

Rick

Berman is a studio potter, workshop leader, and ceramic

historian. He has served as associate editor of Clay Times and teaches

ceramics and sculpture at Pace Academy in Atlanta, Georgia. Rick

Berman is a studio potter, workshop leader, and ceramic

historian. He has served as associate editor of Clay Times and teaches

ceramics and sculpture at Pace Academy in Atlanta, Georgia.

Article and images reproduced by kind permission of

Clay Times Magazine and

Rick Berman. © Rick

Berman.

More Articles

|