| The Onggi Potters of Korea

by Ron du Bois

(color only)

(color only)

This article consists of three parts:

- Article: The Onggi Potters of Korea (this

page)

- The work of Korean folk potter Heo Jin Kyu

- The work of Korean folk potter Yon Shik Bae

|

Korean pottery today is still largely produced as it was

in the past. For a practicing potter it provides a living

case study of historical ceramic processes and techniques.

Potter's wheels, kilns, tools and other equipment are still

made as they were in years past. Machinery is too expensive

to warrant its purchase and maintenance relative to the cost

of man power. Glaze materials are still ground from the parent

rock materials using ingenious two-man pounders. Within a

period of six days, two men working full time can only produce

about sixty pounds of pulverized material. No ceramic supply

houses offer ready made equipment or processed materials suitable

for instant use. Immense quantities of wood must be transported,

chopped and split. In the Vi dynasty the proximity of kilns

to forests was more important than to kaolin deposits. Today

the forests-are seriously depleted; special permits are issued

for the purchase and burning of wood. It is an expensive fuel

but less so than either oil or propane which are imported

products. Natural gas does not exist.

The complexity of the ceramic process is taken for granted,

as is the necessity for a division of labor. Chopping wood,

mixing and decanting clay, slicing, stacking and firing are

assigned to specialists. The authorship of the pottery when

it emerges from the kiln is diffuse, since it is the result

of the coordinated effort of many hands. |

There are four major categories of ceramics produced in Korea

today:

- Onggi, or earthenware utensils, used for a variety of purposes,

but primarily for the storage of pickled vegetables, bean pastes

and soy sauces - staple items of the Korean diet.

- Reproduced Koryo and Vi dynasty forms, for sale primarily to

the Japanese market.

- Tea bowls, again for the Japanese market.

- Pottery produced within university ceramic departments, reflecting,

in varying degrees, exposure to outside influence.

Of the above categories, onggi is of the greatest interest to the

Occidental potter. The techniques and methods used are virtually

unknown in the West. The Korean potter is able to produce monumental

size jars with a speed that seems incredible when witnessed by a

Western potter. The methods of coil, paddle and wheel construction

are outside the spectrum of ceramic skills in the West, particularly

in terms of speed and size.

Because of recent developments in the use of various metals, artificial

resins, and the growth of in9ustrial ceramics in Korea there is

a danger that the production and use of hand· crafted vessels

will die out. Moreover, modern materials and processes may be found

to be preferable to onggi ware, which is less durable, heavier and

higher in price than mass produced pots. Working against this possibility,

however, is the conservative character of Koreans and their firm

belief that the taste of kimchi would be adversely affected by storage

in anything but onggi ware. On the other hand, the new reforestation

laws pose a fundamental danger to the continued firing of onggi

kilns. Wood is scarce and expensive and imported oil is more so.

There seems to be no solution to the high ecological and financial

costs of fuel. Thus, it is difficult to predict the future of onggi

pottery in Korea. But, for the present, at least, the Western potter

is still able to observe the traditional skills of the Korean potter.

Clay Preparation

Beginning

in the 1950's, the onggi potters started to adopt a traditional

Korean technique of refining clay that had hitherto only been used

in the manufacture of high-quality white ware. Thus, the methods

described below are essentially the same both for onggi and porcelain

ware manufacture. About twenty years ago, some onggi workshops on

Kanghwa Island adopted that technique, and its use spread gradually

to Kyonggi and South Ch'ungch'ong provinces. Beginning

in the 1950's, the onggi potters started to adopt a traditional

Korean technique of refining clay that had hitherto only been used

in the manufacture of high-quality white ware. Thus, the methods

described below are essentially the same both for onggi and porcelain

ware manufacture. About twenty years ago, some onggi workshops on

Kanghwa Island adopted that technique, and its use spread gradually

to Kyonggi and South Ch'ungch'ong provinces.

A field approximately 75' x 75' is used for the drying of clay.

At each corner of the field a round hole approximately eight feet

in diameter is dug out. These are settling vats. Today they are

sometimes lined with cement. A smaller rectangular vat approximately

two by four feet is built tangential to each of the circular vats.

Small wooden connecting dykes allow water from each settling vat

to flow back into the mixing vat as water is needed. Raised earth

levies divide the ground between the mixing and settling vats into

drying fields. In addition they serve as dry footpaths from which

workers are able to remove the dried chunks of clay.

Refining Procedures

- Drying. The raw clay is dried in order to assure that

it will slake more quickly in the refining vat. The clay is scooped

up with a "three-men shovel" and piled in a sunny place

to dry. It is then spread and evened with a wooden rake or hoe.

Lumps of clay are broken with the hoe and large stones are picked

out. The clay, in the form of soft shale, does not break or slake

easily. The dried clay, broken roughly into lumps no larger than

apples, is taken to the refining area in a basket or cart. Often

an A-frame is used to carry about two hundred pounds to the mixing

vats.

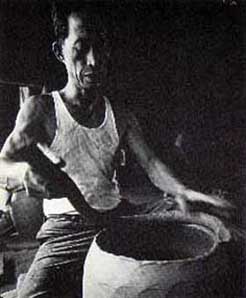

- Mixing and slaking. The clay is dumped from the cart

or A-frame into the mixing vat containing water. After the clay

has begun to dissolve in the water, it is stirred with a wooden

paddle to which is affixed a handle with a cross bar at the end.

The clay is levered up and down using the edge of the mixing vat

as a fulcrum. The soft shale does not slake easily and a constant

up-and-down motion of the paddle is necessary to partially dissolve

the clay and produce a watery slip. The mixing process involves

long and repetitive labor; women are assigned to this task since

they can be paid less. To the Western observer it seems incredible

that so much labor is expended on a process that could be accomplished

easily and quickly by an electric blunger.

- Screening the clay. The thin slurry thus produced is

scooped out with a bucket and poured through a thirty-mesh screen

into the second or settling vat. The screening assures that clumps

of clay, sand and pebbles do not enter the second vat. When more

water is needed to continue the mixing process, that gate of the

small dyke is removed. The relatively pure top layer of water

from the second vat flows back into the mixing vat.

By repeated mixing, screening and return water flow the clay in

the vat is eventually used up, leaving only stones and sand. These

are removed with a shovel; more water and raw clay are added,

and the process is begun again. Approximately a week is required

to fill the settling tank with thick slurry. When the second vat

has been filled with screened clay slip, it is scooped out with

buckets and taken to the drying field, using the raised levies

as walkways.

- Drying the slip to the plastic stage. The ground of

the storage area is first covered with a layer of hemp or cotton

cloth about 15' x 15' in order to prevent impurities from the

ground getting into the clay and to facilitate removing it when

it dries to a plastic stage. The clay slurry is spread on top

of the cloth and the moisture in the clay is evaporated by the

sun and wind. When the clay has been dried to a plastic stage,

it is scored with a small scythe and the chunks approximately

12" x 12" x 6" are carried to a cart, in which

they are transported to the workshop.

- Further preparation of the clay. In the workshop the

chunks of clay are stacked to form a rectangular mass approximately

six feet in length, four feet in width and four feet high. Water

is sprinkled on the clay and it is beaten with a long wooden mallet,

first with he head, then with the side, by workers mown as saengjilggun.

The clay that has been tacked on the workshop floor is then cut

into thin slices about 1/8" in thickness with a scythe-like

knife. This part of the second processing is performed by workers

known as 'hardy lads" or "clay slaves." The main

reason for slicing the clay is to homogenize the distribution

of soft and dry clay.

The "hardy lads" next roll the clay into balls weighing

forty or fifty pounds. In some workshops, a sheet of cotton cloth

is laid on part of the workshop floor and the balls of clay are

put on top of this; in others kaolin is spread directly on the

earthen floor.

The balls of Clay are stacked up until a rectangular mass 10'

x 10' x 3', i.e., about two and one half tons, is formed. The

clay is always beaten first with the head of the mallet, then

with the side of the mallet. The mass of beaten clay is then sliced

a second time into balls and, for the second time, pounded. After

the second pounding the mass of clay is then cut into chunks using

a wooden shovel which is carved monoxylously, i.e., from a single

piece of wood. These chunks are turned over to form a new mass

which is again pounded and cut with the wooden shovel into about

hundred-pound squares of plastic clay.

Clay prepared in this way is as well mixed as by a pugmill. In

addition, the pounding of the clay may account for the peculiar

wet strength and toughness of onggi clay. Several squares, which

will be put to use immediately, are set aside and the rest are

covered with a damp cloth or plastic sheeting to keep them from

drying. The thick sod walls, heavy thatch roof and small windows

of the workshops are deal for retaining the moisture content of

these "mountains" of clay.

The squares of clay that have not been covered are taken to a

place just beside the potters' wheels where they are cut by wire

into oblong shapes about 18" x 3" x 3" weighing

some twenty pounds.

|

Coil Construction

A "hardy lad" quickly moves one of these oblongs

to a relatively flat area of the earthen floor where he begins

to make lateral throws of the clay, quickly extending its

length to some 36 inches. This bar is slightly twisted to

form a spiral cylinder of clay. The techniques of twisting

the clay bar assures the easy transition from bar form to

a smooth even coil. The coil is next reduced to a diameter

of 1 V2" and extended about 6 feet in length by rolling

it backwards and forwards on the earth floor. A pile of these

coils is laid next to the potter's wheel ready for use. |

|

Forming the Base of the Vessel

A ball of clay about eight pounds in weight is hand wedged

into a cylinder about 41/2" in diameter and 6" long.

This roll of clay is picked up and given several throws on

the earth floor so that a thick disc is formed. This is expanded

to about 16" in diameter and 3" in thickness by

a series of rotations and lateral throws. The disc is placed

next to the potter's wheel. The process is repeated until

a stack of discs are made. |

Flattening the Disc

The potter now positions himself at the wheel and rapidly dusts

the wooden throwing head with dry kaolin powder. The powder prevents

the disc from adhering too strongly to the wheel head and allows

the finished pot to be lifted from the wheel. No cutting wire is

used.

Next the potter centers the disc on the wheel head. While slowly

turning the wheel in a counterclockwise direction, he quickly beats

the clay disc with the pangmangi, or beating stick, which he holds

in his right hand. This thoroughly compresses the particles of clay

and removes air pockets. The potters place great emphasis on learning

this; if it is not done correctly, the bottom will crack either

in the drying or firing stage.

Wall Formation - First Stage

The potter inscribes a circle in the disc to mark off the base

size desired; then he revolves the wheel and cuts off the excess

clay with a wooden knife. Next comes the task of fashioning the

walls of the vessel. At the present time there are three methods

of constructing the walls, each differing slightly from the others.

The most common are the "coil" method, used in Kyonggi

province, and the "spiral coil" method used in Kyongsang

province. The third, even more startling to the Westerner, is the

"slab" method, used in Cholla province. In this technique,

long "slabs" of clay, about three times the diameter of

the pot, 8 inches wide and 3/8 inch thick, are set one on top of

the other to form the vessel wall. These slabs are constructed in

approximately the same fashion as the clay coils except that the

bars of clay, rather than being twisted and rolled into coils, are

flipped in the air and slapped on the ground to form wide "ribbons"

of clay.

The first stage of wall construction consists of connecting the

base of the vessel with the bottom-most part of the vessel wall.

This portion of the vessel wall may be fashioned of the excess clay

from the disc of the clay used in making the base or it may be constructed

of a cylinder of clay made especially for this purpose. A coil of

clay approximately three times the diameter of the base is put on

the wheel. The wheel is rev91ved slowly and the coil beaten flat.

In either case, the flat strip of clay is then attached to the edge

of the base. After this has been accomplished a thin coil of clay

is taken and pressed along the inner seam between the base and the

lower part of the wall. This procedure is done in, order to strengthen

the joint between these two pieces of clay. It is executed with

amazing skill, the knuckle of the right hand pressing the coil into

the joint, the left hand providing exterior support. At the same

time the wheel is rotated slowly with a rapid heel action of the

left foot a method requiring motor skills entirely unknown in the

West.

In the next step the potter takes a coil of clay and attaches it

to the lower part of the wall already constructed. The technique

used in coil joining involves a coordinated pressure of the left

palm on the outside surface of the coil together with a series of

half rotations on the right hand exerting a downward and opposing

lateral pressure. This is performed with virtuoso speed and skill.

The left foot, the toes and ball placed against the pit wall, function

as a fulcrum for the heel of the foot to again perform a rapid series

of forward motions, moving the wheel forward at a speed coordinated

with the work of the hands. The process is repeated until three

or four coils have been applied. In Kyongsang Province, where the

"spiral coil" method is used, the coil, more than six

times the diameter of the pot, drapes over the shoulder of the potter

and down his back. He feeds it continuously for two or more revolutions

of the wheel before the coil is used up.

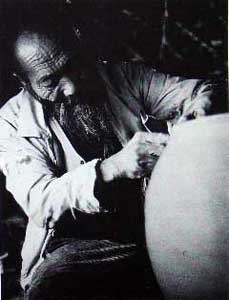

Beating Techniques

The next step involves the use of a wooden anvil, or togae, and

a wooden paddle. The potter beats against the inner and outer surfaces

of the vessel wall with these two implements while at the same time

revolving the wheel with his left foot in a counterclockwise direction.

In this way the coils of clay are completely homogenized and the

walls are thinned. In addition, the clay is compressed and thus

becomes stronger. This completed, the potter takes up two scrapers.

The one used as an inside scraper is usually a sea shell, although

stiff metal scrapers are also used; the other is an outside wooden

scraper which is larger. The latter is held in the right hand and

the former in the left and applied to the inner surface. The potter,

holding the scrapers rigidly opposed to each other, turns the wheel

rapidly, "pulling" at the wheel with his left leg. To

maintain this sort of strength in the muscles of the left leg requires

constant exercise of these muscles. Sore leg muscles are inevitable

if the potter begins to work again after a period of inactivity.

The next stage is the construction of the mid-section of the wall

using the same sequence of coil application, paddling, and scraping.

The same sequence is repeated to complete the top section of the

vessel. This completed, the potter takes the wooden knife to trim

the top edge. He then takes a moistened strip of cloth, the central

section of which is laid on the top edge, the rest of the strip

falling downwards on the inner and outer surfaces. Holding the strip

firmly in both hands he turns the wheel, allowing the cloth to create

a thickened lip form.

Final Procedures

With a shorter and thinner piece of cloth pinched between the fingers

of the right hand he creates a raised linear decoration just above

and below the "body" of the vessel. He supports the inner

wall with his left hand as the wheel turns. The vessel is now completed,

save for its removal from the wheel. He then trims the bottom of

the vessel with "bottom cutter" or wooden knife, turning

the wheel at the same time. For a large pot the potter gets the

help of one of the "hardy lads" to lift the vessel from

the wheel with a piece of cloth. The cloth, measuring about two

by four feet, is wrapped around the vessel. The two men, positioned

on opposite sides of the vessel, simultaneously pull upwards on

the cloth, hereby lifting the vessel from the wheel. It is hen moved

to a special shed called the iongch'im, constructed with thatch

roof but without walls, where it is set down. The cloth is removed

and the vessel is allowed to dry for several days, depending on

temperature and humidity. It should be noted that the method of

construction makes it unnecessary to trim the bottom of the vessel;

even so, the walls of a pot four feet in height are uniformly thin

from top to bottom.

Ron du Bois, potter and instructor of ceramics at Oklahoma State

University, spent 18 months in Korea on a Fulbright scholarship.

His work with the folk potters of Korea resulted in an award winning

film, The Korean Potter, which can be obtained through The Daniel

Clark Film Library, Box 315, Franklin Lakes, NJ 07417.

More Articles |