| Feats of Clay

Kathmandu Valley’s famous pottery has to change

with the times.

Article by Alexandra Alter

Originally published in the Nepali

Times.

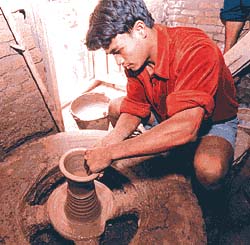

Everyday

since he was a pint-sized 12-year-old, Tulisi Bahadur Prajapati

(ed. note: in the Newari language the surname means

'potter') has collected clay and kneaded it with his feet.

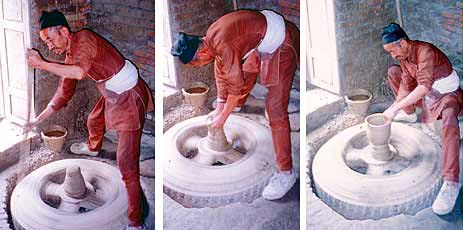

It's tiring, but nothing compared with what follows. Thimi's Prajapati

potter community doesn't use the elegant little wheels most of us

picture potters working with. They use old tyres filled with concrete

that weigh more than 300 kg (ed. note - probably

only up to 100 kg). Starting the wheels is so laborious,

it is the only aspect of pot-making that Thimi's women don't participate

in. The men turn these improvised wheels with a pole at a frenzied

pace until the tyre is spinning fast enough for them to throw two

or three pots in about five minutes. “It's incredible that

the pots are so symmetrical. They're thrown so quickly and the tyre

is so unstable and unpredictable,” says Ani Kastan, an American

potter who studied potting methods in Thimi. Larger pots, such as

the deodas used to store chhang, are first built up out of clay

coils and then beaten smooth with a paddle. Everyday

since he was a pint-sized 12-year-old, Tulisi Bahadur Prajapati

(ed. note: in the Newari language the surname means

'potter') has collected clay and kneaded it with his feet.

It's tiring, but nothing compared with what follows. Thimi's Prajapati

potter community doesn't use the elegant little wheels most of us

picture potters working with. They use old tyres filled with concrete

that weigh more than 300 kg (ed. note - probably

only up to 100 kg). Starting the wheels is so laborious,

it is the only aspect of pot-making that Thimi's women don't participate

in. The men turn these improvised wheels with a pole at a frenzied

pace until the tyre is spinning fast enough for them to throw two

or three pots in about five minutes. “It's incredible that

the pots are so symmetrical. They're thrown so quickly and the tyre

is so unstable and unpredictable,” says Ani Kastan, an American

potter who studied potting methods in Thimi. Larger pots, such as

the deodas used to store chhang, are first built up out of clay

coils and then beaten smooth with a paddle.

After

the pots are completed they are dried in the sun, then fired in

communal, makeshift kilns, that are built and destroyed every four

days. Pots from each workshop are taken to the town square, where

they are stacked up, covered with straw and ash, and then burned

in a kind of smoke firing. Smoke and ash billow through the town's

streets. Not surprisingly many Thimi residents have chronic lung

problems. When the fire subsides and the ash is swept away, the

pots are left to cool. It's common for over fifty percent of the

pots to be destroyed during the firing process. Those that survive

the firing are carried around to different villages in yokes and

are sold door-to-door. “My father used to walk all the way

from Thimi to Swoyambhu selling his pots,” Santa Kumar Prajapati

remembers. Today some potters have resorted to vehicles, but many

still sell their wares by travelling on foot. After

the pots are completed they are dried in the sun, then fired in

communal, makeshift kilns, that are built and destroyed every four

days. Pots from each workshop are taken to the town square, where

they are stacked up, covered with straw and ash, and then burned

in a kind of smoke firing. Smoke and ash billow through the town's

streets. Not surprisingly many Thimi residents have chronic lung

problems. When the fire subsides and the ash is swept away, the

pots are left to cool. It's common for over fifty percent of the

pots to be destroyed during the firing process. Those that survive

the firing are carried around to different villages in yokes and

are sold door-to-door. “My father used to walk all the way

from Thimi to Swoyambhu selling his pots,” Santa Kumar Prajapati

remembers. Today some potters have resorted to vehicles, but many

still sell their wares by travelling on foot.

Tulisi Bahadur, now in his seventies, may have entered

the family trade at the age of 12, but claims he learnt the art

of pottery at a much younger age. Like many of Thimi's children,

he began making pots as a toddler, playing with clay and imitating

his father. Today, he and his wife Chinimaya maintain his father's

pottery workshop on the first floor of their house, where they spend

long hours throwing pots.

But of their four children, only their daughter has

chosen to follow the family trade. Their three sons have moved to

Kathmandu to work as tailors and in knitting factories. Even their

daughter now works in her husband's workshop, leaving the couple

with no one to bequeath their studio to. “I had hoped that

all my children would become potters, but I didn't want to interfere

with their wishes,” says Tulisi Bahadur.

Nearly

all of Thimi's inhabitants, who belong to the Newar Prajapati caste

of potters, say their trade extends far back in their bloodlines.

But of the estimated 8,000 Prajapatis who live in the area surrounding

Thimi, only 2,000 claim that profession today. The others, like

Bahadur Prajapati's sons, have sought more lucrative work in Kathmandu

as bus drivers, waiters, or factory workers, leaving many family

pottery workshops without an heir. Nearly

all of Thimi's inhabitants, who belong to the Newar Prajapati caste

of potters, say their trade extends far back in their bloodlines.

But of the estimated 8,000 Prajapatis who live in the area surrounding

Thimi, only 2,000 claim that profession today. The others, like

Bahadur Prajapati's sons, have sought more lucrative work in Kathmandu

as bus drivers, waiters, or factory workers, leaving many family

pottery workshops without an heir.

The high rate of defection from the potter trade is

disconcerting, but by no means surprising. Potters all over Nepal

work extremely hard for little economic compensation. Most of the

potters in Thimi adhere to the arduous traditional methods in which

every aspect of pottery production is completed manually - from

mixing and drying the clay to powering the wheel. Of the roughly

1,000 workshops in Thimi, only four or five use modern potting technology

such as electrically powered wheels and kerosene-fuelled kilns.

Since they don't have enough land to grow their own

food, many potters walk to farms when rice and wheat are being harvested,

trading storage pots for grain. They make just enough profit to

survive on. “I go to Kathmandu to sell pots when I run out

of money,” explains Tulisi Bahadur. But even that is a challenge

today. Few Nepalis are interested in earthenware pots when they

can buy cheaper, longer-lasting mass-produced kitchenware made of

steel or plastic.

With such impediments to their livelihood, it's no

wonder that so many of Thimi's potters have forsaken their ancestral

vocation. “Pottery is a very difficult profession now. It's

hard work for little money,” says Santa Kumar Prajapati, who

owns Thimi Ceramics. Santa Kumar and his brother Laxmi Kumar realised

early on that the obstacles facing the Valley's potters in producing

and marketing their wares would only increase, and so in 1985 founded

Thimi Ceramics, one of the town's first modern workshops. Moving

with the times has allowed Santa Kumar and Laxmi Kumar to be innovative

- and remarkably productive. In addition to electric wheels and

pugging machines to mix clay, the brothers own one of few kerosene-fuelled

kilns in the area, which can fire up to 3,000 pieces of glazed ceramics

at a time. Unlike the unpredictable straw kilns used by most of

Thimi's potters, the temperature in the brick kiln is adjustable,

allowing the ceramics to first be fired at a low temperature and

then refired at 1,000 degrees after they have been glazed. The double-firing

technique melts the glaze and ensures that the ceramics are durable.

“Nepalis don't want to pay for handmade pots that break easily.

Potters need to find new methods,” believes Santa Kumar.

Retaining traditional procedures isn't always a bad

thing - as a tourist attraction at the Bhaktapur potters' square,

it is a definite plus. But Thimi's potters have a lot more incentive

to alter their archaic techniques - few tourists visit Thimi, and

those who do aren't likely to lug home an enormous water storage

vessel. But as Santa and Laxmi Kumar have discovered, traditional

and modern potting methods can be blended to yield a product as

aesthetically pleasing as it is practical. Combining classical designs

with modern glaze technology, the Kumar brothers constantly create

new models of tableware, garden ceramics, and decorative pieces

that quickly get snapped up by hotels, restaurants, and foreigners.

Their work is found at Hotel Yak & Yeti, Koto restaurant, and

Hotel Kido, and colourfully glazed coffee mugs from Thimi Ceramics

appear to be a staple in any expat's kitchen.

Bolstered

by the success of their own workshop, Santa Kumar and Laxmi Kumar

decided to bring other potters in the area up to speed. There have

been attempts to modernise Thimi's potting techniques in the past,

most notably by Jim Danish,

an American potter who lived in Thimi for nine years to teach more

expedient potting methods. Danish's most significant contribution

to modern Nepali ceramics was glaze technology, which he taught

Thimi's potters in 1980. More than just an aesthetic touch, glazing

serves important practical functions, making ceramics more durable

and hygienic. The red terracotta clay that Thimi potters use is

extremely porous, making it unsafe as kitchenware. Food and liquids

easily seep into the clay and remain there as fodder for bacteria.

Glazing provides a protective shield, and strangely enough, was

unknown in the Valley before Danish introduced it. Bolstered

by the success of their own workshop, Santa Kumar and Laxmi Kumar

decided to bring other potters in the area up to speed. There have

been attempts to modernise Thimi's potting techniques in the past,

most notably by Jim Danish,

an American potter who lived in Thimi for nine years to teach more

expedient potting methods. Danish's most significant contribution

to modern Nepali ceramics was glaze technology, which he taught

Thimi's potters in 1980. More than just an aesthetic touch, glazing

serves important practical functions, making ceramics more durable

and hygienic. The red terracotta clay that Thimi potters use is

extremely porous, making it unsafe as kitchenware. Food and liquids

easily seep into the clay and remain there as fodder for bacteria.

Glazing provides a protective shield, and strangely enough, was

unknown in the Valley before Danish introduced it.

In 1984, Danish founded the Ceramics Production Project,

a German-sponsored organisation that provided training workshops

and sold raw materials relatively cheaply. Ten years later, however,

the project was bought up by the private sector and discontinued

the sale of materials to local potters. That's when Santa Kumar

and Laxmi Kumar started their own collective, the Nepal Ceramics

Co-operative Society, which now supplies materials for 14 pottery

workshops and 37 potters from Thimi and Bhaktapur. “You can't

get all ingredients for the glaze in Kathmandu. For flint, feldspar,

potash, quartz, and chromium oxide we have to go to India. We go

once a year and get enough materials for everyone in the collective,”

says Santa Kumar. The ingredients necessary for glazing would be

prohibitively expensive, as well as difficult for most potters to

obtain, but through the collective they can procure these materials

at a reasonable cost.

In

addition to providing the chemicals and minerals necessary for glaze,

the collective offers workshops for potters who want to learn new

techniques. Three months ago, a Swiss expert came to teach a new

glaze method at the collective. Though Nepal's ceramics are still

fathoms behind the rest of the world in most respects, the glazed

pottery produced here is technically superior to ceramics in Europe,

China, India, and America - it is lead-free and non-toxic. In

addition to providing the chemicals and minerals necessary for glaze,

the collective offers workshops for potters who want to learn new

techniques. Three months ago, a Swiss expert came to teach a new

glaze method at the collective. Though Nepal's ceramics are still

fathoms behind the rest of the world in most respects, the glazed

pottery produced here is technically superior to ceramics in Europe,

China, India, and America - it is lead-free and non-toxic.

Even today, Nepal's ceramic work has been eclipsed

by products from India and China, both of which can mass-produce

more durable stoneware. Kathmandu Valley potters have until now

been limited to the brittle red terracotta clay locally available

and found under the topsoil of rice fields. But members of the collective

are developing ways to introduce stoneware clay to pottery workshops

here. The research is expensive and requires imported Indian equipment.

Even the kerosene kiln operated by Santa Kumar and Laxmi Kumar is

unsuitable for stoneware firing, which requires a minimum temperature

of 1,280 degrees. At such a high temperature, the brick kiln would

melt, resulting in a huge gas explosion. At the collective, however,

a small high fire kiln has been constructed and is being used to

experiment with stoneware clay and new glazes.

If the research at the collective is successful, there

is hope that domestically produced pottery will one day supplant

foreign merchandise in the ceramic market. But Nepal's potters have

a long way to go before they'll be equipped to compete with Indian

imports. “To rival India, we need to be able to produce longer

lasting stoneware ceramics. We'll have to replace all our equipment,

and that's expensive,” says Santa Kumar. Such an undertaking

will require substantial capital investment and time, but for the

moment, the technical advances being made in workshops in Thimi

and Bhaktapur signal that a movement to reinvigorate Nepal's ceramic

work is underway. If nothing else, the Nepal Ceramics Cooperative

society is working to ensure that Kathmandu Valley's pottery tradition

won't decline further.

Article courtesy the Nepali Times. © Nepali

Times. 'Wedging' photo courstsy Jim

Danisch.

The

Thimi, Nepal Potters Community

More Articles

|