Text courtesy Saudi

Aramco World.

In

the mid-19th century, Europe's artistic and fashionable circles

were enthralled by a vogue for all that was Oriental. Visitors

to London Galleries and Paris salon exhibitions became familiar

with Middle Eastern desert and village life, with Arab, Persian

and Turkish costume and decorative arts as they were recorded

- or sometimes imagined - on canvas or in watercolor by European

artist-travelers. De rigueur for Victorian ladies were

the sumptuous, colorfully patterned paisley shawls, while loose,

cool pajamas, as worn in the Islamic world, were adopted into

the well-dressed European male's wardrobe. European homes featured

the new "divan" associated with life à l'orientale

- furniture that invited lounging and relaxation - and the Turkish

bath was introduced to Paris.

In

the mid-19th century, Europe's artistic and fashionable circles

were enthralled by a vogue for all that was Oriental. Visitors

to London Galleries and Paris salon exhibitions became familiar

with Middle Eastern desert and village life, with Arab, Persian

and Turkish costume and decorative arts as they were recorded

- or sometimes imagined - on canvas or in watercolor by European

artist-travelers. De rigueur for Victorian ladies were

the sumptuous, colorfully patterned paisley shawls, while loose,

cool pajamas, as worn in the Islamic world, were adopted into

the well-dressed European male's wardrobe. European homes featured

the new "divan" associated with life à l'orientale

- furniture that invited lounging and relaxation - and the Turkish

bath was introduced to Paris.

The preferred jewelry

motif was the so-called Algerian knot.

Against this backdrop,

the acquisition of a single brilliantly colored Islamic tile

prompted French ceramist Joseph-Théodore Deck to explore

and revive Middle Eastern ceramic techniques in the creation

of his own unique art.

Deck, the first of

the artist-potters in what was to become a widespread revolution

in European ceramics, was born in the Alsatian town of Guebwiller

in 1823. He dreamed of becoming a sculptor, but his modest background

dictated a more prosaic vocation. Deck apprenticed as a maker

of ceramic stoves - large, room-warming structures of ironand

plaster often elaborately covered with ceramic tiles - and traveled

to Germany, Austria and Hungary to learn his trade. Moving to

Paris in1847, he worked as a foreman in a ceramic stove factory.

But by 1856, Deck

had established his own decorative faïence workshop in

partnership with his brother Xavier and nephew Richard. Painters

and sculptors frequented "Atelier Deck," which became a design

laboratory promoting ceramics as an art form in the face of

prevailing industrial practices.

For

Théodore Deck, the 1850's were an exciting decade of technical

research and experimentation. Paradoxically, Deck looked back

into history to develop new and improved ceramic techniques.

He began by exploring lost Renaissance processes, making elaborate

ceramics resembling those of Frances Saint-Porchaire factory,

extravagantly decorated with inlaid strapwork patterns and incrustation.

Next, tantalized by the secrets locked within the luminescent

glaze of his one Islamic tile, Deck began to unravel the mysteries

of centuries-old ceramics techniques of that culture. He wanted

to know more.

For

Théodore Deck, the 1850's were an exciting decade of technical

research and experimentation. Paradoxically, Deck looked back

into history to develop new and improved ceramic techniques.

He began by exploring lost Renaissance processes, making elaborate

ceramics resembling those of Frances Saint-Porchaire factory,

extravagantly decorated with inlaid strapwork patterns and incrustation.

Next, tantalized by the secrets locked within the luminescent

glaze of his one Islamic tile, Deck began to unravel the mysteries

of centuries-old ceramics techniques of that culture. He wanted

to know more.

Since the Middle

Ages, Islamic ceramics had been admired in Europe as much for

their luscious, rich glazes as for their abundant and colorful

decoration (See Aramco

World,

March-April 1992). Early Islamic potters initially developed

their skills from the techniques of their ancestors, but as

long-distance trade and contacts flourished, along the Silk

Roads and by other routes, they adopted many Chinese techniques

to achieve a superior product, and added others of their own.

Many Islamic inventions - tin-glazed earthenware, luster and

underglaze painting - were in turn crucial to the development

of ceramics of other cultures.

Deck discovered that

the brilliant color in Islamic ceramics is due to a base coating

of white alkaline slip containing tin oxide. The decoration,

done in enamel colors, is covered with a transparent glaze,

and produces glowing, translucent effects. After much trial

and error, Deck succeeded in rivaling the vivid palette of colors

characteristic of Islamic ceramics. He created "bleu de Deck,"

his famous deep-turquoise blue glaze, using potash, carbonate

of soda and chalk.

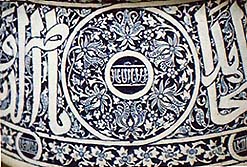

As interested in

decoration as in technique, Deck found prototypes for his "Persian"

faïence (called "Rhodian" in the 19th century) in ceramics

that were in fact Turkish, specifically from the famous Iznik

manufactory in the 16th and 17th centuries. At the time, Iznik

ceramics were celebrated throughout the Islamic world for the

astonishing depth, brilliance and luminosity of their glazes

and colors; they were often boldly decorated with floral motifs

whose stylized forms resembled those found on Persian carpets.

They recalled the Islamic love of gardens, with charming tendrils,

leaves, blossoms and fruits -pomegranate, carnation and tulip

- swaying gracefully across the surfaces of dishes, vases and

tiles. Sprightly animals and highly decorative Arabic calligraphy

also flickered across their lustrous surfaces, and Iznik ceramists

formed beguiling arabesque patterns with flattened leaves, limbs

and letters.

Deck sometimes copied

directly from Iznik ceramics, but he also created variations,

assimilating motifs from several examples into a single object.

While Deck's designs are generally more symmetrical than those

of his prototypes, it is nevertheless sometimes possible to

identify the very pieces that inspired him.

Islamic source material

for Deck to study was hard to come by in 19th-century France.

A small but steadily increasing stream of hardy European adventurers

braved the perils of contemporary travel to experience the wonders

of Turkey, Persia and North Africa. Back home, their exotic

souvenirs perforce became touchstones of Islamic culture and

sparked the European imagination.

One of the first

artist-travelers to the region, Jules-Robert Auguste (1789-1850),

returned to Paris with curios and artifacts of every description,

selected from dozens of bazaars and merchants. At his frequent

"at homes," Auguste displayed costumes, carpets, weapons, ceramics

and glass in a dazzling Thousand-and-One-Nights setting to his

spellbound artist friends, including Théodore Géricault,

painter of "The Raft of the Medusa" - Horace Vernet,

who was to produce the battle paintings at Versailles; and Eugène

Delacroix, greatest of the French romantic painters. Auguste's

souvenirs often found their way into his guests' paintings as

props, and Orientalist subjects - on the increase in the annual

paintings salons - now took on an air of verisimilitude, at

least as far as artifacts were concerned.

Serious

collections of Islamic artifacts began to be assembled in Europe.

Nineteenth-century museums took a didactic approach to acquisitions,

and avidly collected study materials for public instruction

as well as to provide inspirational models to further the applied

arts. The extensive medieval and Renaissance collections of

Paris's Musée de Thermes - Hôtel de Cluny, opened

to the public in 1844, provided Deck with Islamic models to

emulate, and he recorded that its collection contained 132 examples

of "Persian" ceramics.

Serious

collections of Islamic artifacts began to be assembled in Europe.

Nineteenth-century museums took a didactic approach to acquisitions,

and avidly collected study materials for public instruction

as well as to provide inspirational models to further the applied

arts. The extensive medieval and Renaissance collections of

Paris's Musée de Thermes - Hôtel de Cluny, opened

to the public in 1844, provided Deck with Islamic models to

emulate, and he recorded that its collection contained 132 examples

of "Persian" ceramics.

Some Islamic artifacts

had also filtered into France during the Crusades, and fragile

survivors, along with a handful of fine examples of ceramics,

metalwork and glass acquired over the years, had found their

way into the French royal collections. These collections formed

the basis of those of the Louvre Museum, another resource for

19th-century craftsmen.

Deck most frequently

referred to the collection of the National Porcelain Museum

at Sèvres, outside Paris. Open to the public since 1824,

this specialized museum continually added to its large and important

study collection of ceramics from around the world. Underscoring

its avowed mission to provide models for industry, the museum

complex even featured an applied arts school. It was here that

lustrous Islamic glazes gave up their secrets and the sparkling

enamel colors of exquisitely depicted Middle Eastern flora and

fauna seduced Joseph-Théodore Deck.

In the same pedagogical

spirit as the museums, private collectors lent objects to public

exhibitions. On several occasions throughout the 1860's, privately-owned

Islamic works of art were displayed through the auspices of

the newly formed (1864) and commercially-minded Union Centrale

des Beaux-Arts Appliqués à l'Ilndustrie,

the forerunner of Paris's Musée des Arts-Decoratifs. Important

collectors of the period included Baron Alphonse de Rothschild

and Charles Schefer, Emperor Napoleon III's Arabic interpreter.

Ironically,

source material was also supplied by Deck's competition. Ceramist

Eugène-Victor Collinot and his collaborator Adalbert de

Beaumont, who had first encouraged Deck to look to Islamic prototypes,

joined Deck in his early exploration of Islamic ceramics. In

1859, Collinot and Beaumont, themselves collectors of Islamic

artifacts, published Recueil de dessins pour l'art et l'industrie

(A Collection of Designs for Art and Industry), which contained

detailed illustrations of Islamic ceramics and glass seen in

their travels.

Ironically,

source material was also supplied by Deck's competition. Ceramist

Eugène-Victor Collinot and his collaborator Adalbert de

Beaumont, who had first encouraged Deck to look to Islamic prototypes,

joined Deck in his early exploration of Islamic ceramics. In

1859, Collinot and Beaumont, themselves collectors of Islamic

artifacts, published Recueil de dessins pour l'art et l'industrie

(A Collection of Designs for Art and Industry), which contained

detailed illustrations of Islamic ceramics and glass seen in

their travels.

This influential

design book revealed the arts of the Islamic world as a new

source of inspiration to a receptive and enthusiastic audience

of French artists and craftsmen. In its pages Deck found a 13th-century

enamel and gilt glass mosque lamp from Cairo - part of the Rothschild

collection - lavishly decorated with ornament and calligraphy.

Deck translated the bulbous lamp with its wide-flaring neck

into a pair of ceramic vases, replacing its calligraphy with

more floral ornament. Likewise, he converted a medieval Syrian

glass vase illustrated in the Recueil into a ceramic

vase alive with flora and fauna of Persian inspiration. Glazed

in white, black, red and cobalt, the vase's swelling, attenuated

form is enlivened with acanthus, tiny gazelles and bold interlaced

arabesque patterns.

In 1863, Collinot

and Beaumont founded their own faïence factory specializing

in Islamic-inspired wares. Located in the Bois de Boulogne,

the factory caused a sensation with its decoration of blue and

white Islamic dishes. The competition with Deck was truly on.

Nineteenth-century

industrial exhibitions invited such competition. Heavily attended

and the subject of intensive commentary and discussion they

were the manifestation of an era of unprecedented official sponsorship

of the applied arts. Held almost annually, they provided a forum

for exhibitors to present to the public their best and newest,

achievments in the name of progress. His experiments having

come to fruition, Deck presented his first "Persian" faïence

at Paris’s 1861 Exposition des Produits de l'Industrie.

His efforts were rewarded with a silver medal and much critical

praise for his "fine quality" and "intensity of tones."

Deck also met with

success the following year when he introduced metallic luster

glazes, derived from Hispano-Moresque, or Andalusian, wares,

at London's 1862 International Exhibition. While these vitreous,

iridescent glazes were first popularized in Syria and Persia,

they became inextricably linked with Spanish ceramic centers

such as Malaga and Valencia. Arabic inscriptions and floral

and figural motifs predominated within an elaborate overall

design scheme. Deck's prize-winning example was a monumental

vase copied from a model found in the Alhambra, the splendid

14th- and 15th-century Moorish palace in Granada (See Aramco

World,

May-June 1967). The vase's ornate designs were provided

by Baron Davillier, a renowned scholar of Hispano-Moresque ware

and a frequent advisor both to Deck and to the National Porcelain

Museum at Sèvres.

The London exhibition

brought Deck important official recognition: The recently established

South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum),

an active patron of the applied arts, bought three of Deck's

works from the exhibition. Here also, Deck's brilliant colors

caused widespread comment, especially the "bleu de Deck." Its

"dazzling hues seemed like electric sparks," according to one

source.

Then

in 1863, the first year of their factory's operation, Collinot

and Beaumont exhibited their own "Persian faïence" at the

Union Centrale, where their work, like Deck's, was awarded a

first-class medal. Both factories competed again at the Paris

1867 Exposition Universelle and were awarded silver medals.

While critical comparison was inevitable, it was uncharitable

of Deck to snipe that Collinot's "Persian wares were improperly

and unauthentically decorated."

Then

in 1863, the first year of their factory's operation, Collinot

and Beaumont exhibited their own "Persian faïence" at the

Union Centrale, where their work, like Deck's, was awarded a

first-class medal. Both factories competed again at the Paris

1867 Exposition Universelle and were awarded silver medals.

While critical comparison was inevitable, it was uncharitable

of Deck to snipe that Collinot's "Persian wares were improperly

and unauthentically decorated."

Islamic art also

provided contemporary French glass artists with a new source

of inspiration. Philippe-Joseph Brocard began, his career as

France's first art glass-maker by reviving the tedious process

used to make Islamic enameled and gilded glass of the 13th and

14th centuries. Brocard, who first exhibited his work at the

Paris 1867 Exposition Universelle, developed a cloisonné technique,

outlining his designs in thick cells of gold or enamel paint.

He shared many of Deck's sources-plates from Collinot and Beaumont's

Recueil, Egyptian and Syrian mosque lamps and beakers

in the Cluny Museum, and works of art that were part of various

private collections.

Like Deck, too, Brocard's

design repertory consisted largely of floral and geometric ornament

and Arabic calligraphy. But he could not read Arabic and his

calligraphy, understandably, often contained errors. It thus

had only a decorative function on his glassware, lacking the

intellectual or didactic element that Arabic calligraphy usually

contributes to art objects of Middle Eastern provenance.

Brocard in turn introduced

Emile Gallé to the enameled glass of Islam. Better

known today for his turn-of-the-century art-nouveau glass, Gallé's

early work of about 1880 frequently borrowed motifs from Indo-Persian

miniatures and Islamic calligraphy. But instead of arduously

trying to copy Arabic inscriptions which he too could not read,

Gallé simply invented a fantastic Islamicate French-language

alphabet with which he inscribed mottoes on his glass in bright

colors.

Deck explored other

cultures later in his career. In 1884, he exhibited flambé

glazes in imitation of Chinese sang de boeuf. Deck's

celadon glaze, used over designs incised in the body of the

ceramic, also referred to Chinese origins, as did his many experiments

with porcelain and with decorative craquelure effects. The asymmetrical

designs and motifs of Japanese ceramics that were exhibited

at Paris's 1878 Exposition Universelle were promptly reflected

in Deck's offerings in the 1880 Union Centrale exhibition. No

less exotic, Venice's glittering Byzantine mosaics inspired

Deck to develop an underglaze gold to be used for background.

Because of his range

of technical innovations and accomplishments, Deck was made

art director of the Sèvres manufactory in 1887, the first

ceramist to assume this prestigious post. In the same year,

he published an exhaustive treatise called La Faïence.

Half-historical, half-technical, it testified to Deck's debt

to the potters of Islam. Deck continued to develop and improve

the ceramic art at Sèvres, while his brother Xavier was

charged with running the Paris workshop. After his untimely

death only four years later, Deck was buried in Montparnasse

Cemetery, beneath a tomb Xavier had appropriately decorated

with floral ornament in colored faïence.

Deck's influence

spread through the many artists and sculptors who worked in

his studio or in collaboration with him. In the 1878 exposition,

Deck exhibited wall plates with designs by, among others, ceramist

Albert Anker, painter Henri Joseph Harpignies and caricaturist

and lithographer Ferdinand Bracquemond, who popularized the

Japonisme movement in French art. Even celebrated society

painter Paul César Helleu once designed plates for the

workshop.

But it was Deck himself

who began the ceramic revolution. He was the first to explore

historical styles in the name of progress in ceramics - a process

that continues today (See Aramco

World,

May-June 1990). Increasingly, a concern for the values and

techniques of handicraft began to make itself felt in all the

applied arts in his day, and that concern also continues to

have repercussions in our own time. At the height of the industrial

revolution, Deck returned to the artisanal tradition, laying

the ground for the widespread art pottery movement of the next

two generations. By the 1890's, that movement was widespread

in Europe and the United States, and it had become commonplace

to look to non-European prototypes for inspiration in technique

and decoration. With Deck's vindication of the value of historical

survivals, his work marked the beginning of a new era in faïence.

Frederica

Todd Harlow is an art historian who writes and

lectures on revival styles in the decorative arts.