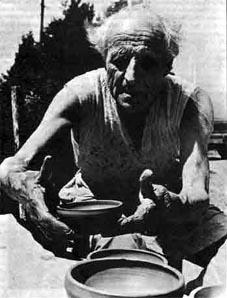

| Michael Cardew 1901-1980

Nigerian Field Vol 66 Pt.2 Oct 2001 - Michael Cardew and the

Abuja Potters by Liz Moloney

The following article is courtesy of the Nigerian

Field Society and the author Liz Moloney. © Nigerian

Field Society. Photos by Doig Simmonds ©1959. Donations may

be made to the society via UK Vice President, Joyce Lowe, email

unitedkingdominfo@nigerianfield.org.

|

The Ladi Kwali

Pottery in Suleija is 54 years old this year. It has not been

a working pottery as long as that, it is true; but it was

in August 1951 that the English studio potter, Michael Cardew,

recruited by the Nigerian colonial Government in 1950 as pottery

Officer, moved up from Lagos to the small town then called

Abuja and started, with a small team of local workmen to build

the new Pottery Training Centre. Ladi Kwali was not to join

the trainees there until the end of 1954, but Cardew had already

been excited by her beautiful pots in the village of Kwali

and hoped to persuade her to come and work with him. Looked

at from the vantage point of 2001, for the colonial government

to start busying itself about the “improvement” of the pottery

techniques of Nigeria it was odd thing to happen, considering

that Nigerian pots, made according to the traditional method

practiced for centuries, were are magnificent already. The

decision to do this, however, resulted in the potters who

made then. Michael Cardew was one of the best publicist ever

for West Africa`s traditional potters even as he worked to

create a new network of rural Potteries using techniques foreign

to the region. |

|

He went to Nigeria when he was 49, not because

he had an urge to change Nigerian pottery but because he desperately

wanted to get back to west Africa where he had unfinished

business after 5 years spent in Ghana ( then Gold Coast )

1943-1948. He was deeply attached to a young potter there,

Clement Kofi Athey, who was running the pottery at Vume they

had set up together, but had had to return to England after

re-current ill-health and he felt he owed it to Kofi not to

allow that project to fail. From Nigeria he thought he could

keep in touch, and visit during his leave, for the sake of

his obsession with Africa he left behind him once again his

pottery at Wenford bridge in Cornwall ( rented out), his wife

(teaching in London), three young sons ( still at school)

and his reputation as an outstanding studio potter ( known

to few, even among the British, in Nigeria ). Of course, Nigeria

took him over and altered his motive.

He did a preliminary tour of the Western region, and quickly

reported to the department of commerce and industries that

some of their ideas needed modification, he could hardly do

himself out a job by rejecting them altogether, given his

desire to be in West Africa and work with West African Potters.

|

Ladi Kwali making pots on a wheel, ca 1959

|

The Pottery, Abuja c 1959, left woodstove, right kiln

The Pottery, Abuja c 1959, left woodstove, right kiln

| In fact the job

description he had been given was not about changing traditional

pottery but about setting up a sort of inter mediate technology

project, a rural industry using the wheel, glazes and high-firing

in the European studio pottery tradition. It was evidently

prompted by the perceived need for a home-grown industry to

supply the middle-class Nigerian demand for a glazed tableware

suitable for European-style meals and hot drinks, at that

time already supplied by factory-produced imports.

Cardew`s first report of July 1950 states

that a wholesale transformation of the Nigerian native pottery

industry is considered to be neither practicable or desirable`,

although he said this idea had been widely entertained by

non-technical observers. This native industry had ‘technical

advantages peculiar to it, which the others do not possess’,

was ‘distinguished by simplicity and nobility in shape and

decoration’, remarkably cheap to produce, and ‘in a healthy

state and not likely to suffer from the competition of locally-produced

glazed wares.’ He pointed out that glazing and high-firing

to make the proposed table ware non-porous ‘ would largely

lose one of the great virtues of the native pottery - tolerance

of the thermal shock.’ He felt able to support the argument

for a home industry to run parallel to the local village pottery,

producing pots for a modern middle- class westernized life

style. he proposed small ‘experimental stations’ with small

numbers of trainees, rather than a central school of ceramics.

This report resulted in his promotion to

senior pottery Officer, and for the next two years he was

involve in the setting up of pottery at Okigwe and Ado-Ekiti

with other British pottery Officers, V A Gregory and S Atkins.

But the decision about where to put the northern region pottery

training Centrex turned out to be the crucial one for Cardew,

and for a number of Nigerians whose lives were changed by

it.

The notes, illustrated by sketches, for his

second report in early 1951, following a tour of Nigeria`s

Northern Region in November and December 1950, show his excitement

as he discovered its varied pottery; he especially admired

the pots made by women in the Abuja area. He was able, as

a colonial Officer, to call upon an impressive network of

existing knowledge to help him. Local potters, district heads,

administrators, miners, Geologists Educationists Missionaries

- all sorts of people knew about the soil structure, the transport

systems, the fuel, the traditions and other factors he had

to consider in deciding how to proceed, and in particular,

where to site the Pottery Training Center. He was allowed

to use the Furnaces of the Amalgamated Tin mines of Jos to

test clay samples. It was a unique support system for a researcher

into traditional pottery as well as prospective local potter.

‘We decided ABUJA after all!’ he wrote in

his note after a meeting in Kastina with Stanhope (Sam) White

of the department of Commerce and Industries, Kaduna, in April

1951. ‘Good and central for N.Nigeria, Wonderful local pots,

a nice town where trainees can live, Hausas would not be out

of place there, and above all, a 1st rate Emir – yes, hurray

!!!’ The ‘after all’ meant ‘in spite of Abuja’s not being

on the railway’, but as it was to be a training center and

not a commercial production Center, this was decided not to

be crucial. Abuja was the place for ‘inspiration’, he said,

and that would made for good pots.

From late August 1951 he supervised the building

of the pottery at Abuja, locally thatched buildings; (the

present ones were built in 1973 ) and started selecting trainees.

Who were these to be? An aspect of the European-style pottery

which contrasted with African pottery was the fact that the

trainees were expected to be men, where as most of Nigerian

potters were women. Hausa land was the big exception, although

within northern Nigerian there were also non-Hausa communities

with women potters. The Abuja emirate was Hausa, that its

population was overwhelmingly Gwari and included outstanding

Gwari women potters. Cardew, in his 1950 report, said he envisaged

the new techniques being mainly to men with only a ‘Small

fringe’ of women potters.

This could be for a numbers of reasons, some

referred to elsewhere in Cardew’s writings such as the fact

that in the traditional industries, potting was,in parts,

the whole way of life, not something as a western industrialized

society and regarded as a career. Men would found it easier

to train and join a paid work- force, because they were less

encumbered by family commitments. This view may be regarded

as reflecting British prejudices and practices and distorting

African Society structure, as happened in the case of Agricultural

and other training. Or you could see it as a realistic appraisal,

since Cardew had already suggested that the traditional, mainly

women, potters would not adversely affected by a new small-scale

industry and African societies, like British once at the time

also tended to separate men’s and women’s work. He had himself

always worked with other men in both England and the Gold

Coast, except when apprenticed with Bernard Leach, and would

probably be inclined to prefer this.

As it later turned out, the Abuja Pottery

Training Centre`s star potter ( Cardew would have hated the

description of any potter as a star, but that was exactly

what she became on overseas tour ) was a woman, Ladi Kwali,

whose basic skill and genius, he always freely acknowledged,

were fully developed before she joined him. But there were

always more men than women working with Cardew. It is odd

in a way that he went along with the argument for a separate

work force outside the old social structures, given that he

always professed a desire to eliminate the distinction between

one’s working life and everything else, and to achieve an

undivided life as had been done in pre-industrial England.

But he had to work within a framework of an administration

struggling to show that it was modernizing the northern region

of Nigeria. I suspect that this masculine bias involve all

sorts of different reasons. |

| So the earliest

trainees were Hausa men, Audu and Gwadabe from Kano, Closely

followed by men from other regions with an increasing number

of local potters. Among the first to start were Okoro Ike

from the south-east, Tankol Ashada Mohammed and Bawai Ushafa.

Audu Mugu and Sidi came down from Sokoto. Later came Bako

Maigari, Audu (Wahala) and Musa (Nawa) Nok in 1956, Mohammed

Inuwa, Hassan Lapai and Usman Zukoko in 1957, Ibrahim Muhtari

Zaria and Peter Bute Kuna Gboko in 1957, Gugong Bong, Bala

Yawa and Abu Karo in 1958 . Kofi Athey, though continuing

to run the Vume pottery in Ghana, worked at Abuja for several

stints of a few months before coming to Nigeria to run the

new Jos pottery in 1963. The kiln gang, who remained throughout

Cardew`s time and later, were Danjuma Kilin, Husseine, Gwari

and Na`anabi.

However quite early on, Cardew`s preference

for male trainees was overridden by his respect for superb

skill and his wish to work with people endowed within. In

the Abuja area, these were women. He had wanted to bring Ladi

Kwali into the training Centrex from the beginning, and finally,

after negotiations with her and with the local authorities,

she arrived in December 1954.She learned to throw ordinary

tableware and smaller pots for practical use, but she also

continued to hand-build pots, which were then controversially

glazed and high-fired. Cardew was well aware of the drawbacks

of this procedure in terms of weight and utility. They were

much less breakable than traditional pots though, and they

became Collector`s treasures, now worth huge sums at auction

which neither Cardew nor Ladi herself could ever have envisaged.

Cardew`s international reputation played

a key role in putting Abuja potters on the international ceramic

world map. He had previously exhibited at the Berkeley Gallery

in London, and was able to arrange for Abuja exhibitions there

in 1958 and 1959, which increased his own fame and made Ladi

Kwali in particular a name in the pottery world. Her success

opened the door to other women potters: Halima Audu from Ido,

came in 1959, and made some superb pots (in Britain, her work

can be seen in the Milner-White collection at York City Art

Gallery.) She died tragically young only two years later.

Asibe Ido and Lami Toto arrived in 1963, followed by Kande

Ushafa. At the time of Cardew`s departure in 1965, the four

surviving women along with six men - Tanko Ashada, Gugong

Bond, Peter Gboko, Abu Karol, Ibrahim Muhtari and Bawa Ushafa,

plus Danjuma Landam, Assistant pottery Officer, were still

at the Abuja Pottery training center. The Kano and Sokoto

Potters had gone back to their home towns, and Okoro had gone

to modern ceramics in Umuahia. |

Above - Ladi Kawli's pots being fired

in the traditional way

Some of these potters and no doubt others who never

left there villages, were also outstanding, but Ladi Kwali remained

grande dame of the Abuja pottery. In 1962 she spent three weeks

in England demonstrating Gwari pot – building techniques, attending

another Berkeley Gallery Exhibition of Abuja Pottery and received

the MBE. Coming back to Abuja she was so full of her experiences

that other staffs sardonically nicknamed her ‘Radio London’, ( as

Michael O’Brien, who came to Abuja soon afterwards and later took

over from Cardew, recalls). later she was awarded an honorary Doctorate

of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria , an unprecedented academic distinction

for a woman potter without formal education.

She would certainly not have granted this if she

had not been ‘discovered’ by Cardew and then the world outside Nigeria.

Michael Cardew stayed at Abuja until 1965, normally spending ten

months there and two on leave at Wenford Bridge in every year, but

also going back to Ghana occasionally to help Kofi at Vume. Abuja

turned out to be just as pleasant a place in which to run a pottery

training center as he had envisaged in his diary notes of 1951,

and the Emir,the famous Suleiman Barau,was even better than ‘1st

rate’,being a friend, supporter and advisor in everything. But it

was not an easy life. Cardew`s early Nigerian years involved him

in relentless physical slog, following in the footsteps of the great

geologist Falconer on camping treks of several days at a time in

his search for kaolin, feldspar, limestone and other raw materials

for pottery and glazes. He was already in his fifties - much older

than the Nigerians who accompanied him -and continued to suffer

regular bouts of ill-health, including bilharzia and from the results

of some dramatic car accidents.

Cardew was unique in his relationship with Nigerian

potters, But he was also part of a group of British people in the

1950s who tried, in the run-up to independence, to make sure that

Nigerian art and history were appreciated and preserved for the

people of Nigeria. these included Bernard Fagg, who excavated the

Nok culture, started the Jos museum and instigated instigated the

magnificent collection of pots there;Sylvia Leith-Ross, who collected

the pots for jos at the already distinguished career in education,

the historian Michael Crowder, who succeeded E.H.Duckworth as editor

of Nigeria Magazine and Kenneth Murray, first Survey of Antiquities.

He wrote the introduction ‘pottery techniques in Nigeria’ for Sylvia

Leith-Ross’s Nigerian pottery ( Ibadan,1970) and articles on traditional

pottery for Nigeria Magazine as well as his book pioneer pottery

for studio potters starting up in similar conditions.

The Abuja Pottery Training Centre never fulfilled

the early aim of spreading a network of small potteries, run by

potters trained there, to supply new Nigerian needs.By the late

fifties it has become a show piece celebrated in Nigeria and abroad,

and sold mainly to expatriates and members of Nigerian elites. the

best pots were put aside for London or other European exhibitions.

Peter Dick, a british potter who worked at Abuja in 1961-2, remembers

the staff saying ‘Sai London! Sai paris!’ when an exceptionally

good pot emerged from the kiln.

Potteries started by Abuja- trained potters under

Cardew’s guidance in Sokoto and Kano failed within a few years,

largely, Cardew said in later discussions with O’Brien, because

as government employees the workers never worked hard enough or

use enough initiative to make them succeed. The later Jos pottery,

founded with help from Bernard Fagg and money from an American ‘fairy

good mother`, did continue under Kofi Athey.

How did the training centre continue to obtain

government finance well into the era of independence Nigeria? It

was never commercial until after cardew’s departure ( under Michael

O’Brien}and its original purpose of created a network of rural industries

to supply to supply Nigerians with a tableware made locally from

local materials had not been fulfilled. Was Cardew just lucky to

find modest but secure patronage for a marvelous experiment in Anglo-Nigerian

cross-cultural ceramics,because of the particular circumstances

of northern Nigerian? Certainly the publicity Abuja brought to Nigeria

at a crucial time in its history was favorably viewed by both the

late colonial and new Nigerian governments.

Michael Cardew, having left Nigeria rather reluctantly

( though well past civil service retirement age at 64 ),did not

cease to be involved with his old friends. Ladi Kwali went on another

triumphant tour demonstrating her work, this time to the United

states in 1972 with Cardew and Kofi athey assisting and explaining

where necessary. She has continued working at the pottery, and one

the most delightful scenes in the BBC television film of 1974 Mud

and Water man shows her greeting Cardew on her return visit to his

old place at Abuja with its new buildings. He continued his active

and international life until his sudden death in Cornwall in 1983.

Ladi Kwali died at almost the same time but at a much younger age

in Minna. Kofi Athey, after leaving Jos at about 1990, worked in

the early nineties at Margaret Mama’s Jacaranda pottery, also near

Kaduna, with some other Abuja staff trained by Cardew, and is believed

to died in Ghana in the 1990’s. The Emir of Abuja, who was so vital

a part of this ( as of other developments in his emirate), has also

died. So what is left ?

There has been small but significant continuing

results from this unusual episode in late colonial history, and

this obsession of an English potter. There was of course the impact

of Ghana and Nigeria on Cardew’s own work, for the pots of his west

African period are generally agreed to have been among his best.

But also he gave a unique training to his small group of trainee

potters and stimulated appreciation, both in Nigeria and elsewhere,

of traditional pots and potters.

The Ladi Kwali pottery at Abuja is still government–owned

and employing staff, but reports suggest it is not producing much

pottery. I have not yet been able to visit it to see for myself.

Perhaps the Anglo-Nigeria studio pottery movement

started by Cardew is being upheld more effectively elsewhere in

the country. Michael O’Brien, Cardew’s colleague and immediate successor,

continues to spent much of his time unobtrusively helping Nigerian

potters. One such is Danlam Aliyu of Al Habib pottery, Minna, who

was trained by O’Brien at Abuja and then by Cardew at Wenford Bridge,

his pottery in Cornwall. Danlami has written in Pottery Quarterly

about his work and the fact that his work is different from that

of local women but in no way supplants it. His brother Umaru also

runs a successful small pottery, the Maraba near Kaduna. Others,

though not directly connected to Cardew, have found inspiration

in his work for similar subjects in other parts of Nigeria. Cardew’s

forecast that traditional pottery would not be threatened by this

studio pottery has been proved correctly. The threat comes from

much bigger forces. Cardew’s was a ‘small is beautiful’ enterprise,

embodying his care for, and enjoyment of, the people and their environment.

This article arises from research for a project

biography of Michael Cardew’s work in west Africa from 1942 to 1965.

I would like to thank Michael O’ Brien, Cardew’s successor at Abuja,

and Michael Cardew’s eldest son, Seth Cardew, of Wenford Bridge

Pottery in Cornwall, for their great help with this project, as

well as Cardew’s friends and colleagues who have contributed their

recollections.

REFERENCES

- Cardew M.A. 1950 A preliminary Survey of pottery in West Africa

(report). Lagos, Department of Commerce and Industry

- 1951 A Tour of parts of Zaria, Plateau, Niger, Ilorin and Kabba

…(report) Lagos Department of Commerce and Industry

- 1952 “Nigerian Traditional Pottery,” Nigeria Magazine3

- 1961 “Firing the Big Pot and Kwali,” Nigeria Magazine 7

- 1962 “ Traditional Pottery. The pottery training Centre,” in

Alhaji Hassan and Mallam Shaibu Na’ibi, tr.F.Heath,

A chronicle of Abuja, African Universities Press, 2nd ed. Lago

- 1969 Pioneer Pottery. London: Longma

- 1988 A Pioneer Potter: An Autobiography. London: Collin

- 1989 A Pioneer Potter (paperback) Oxford University Pres

- 1970 “Pottery Techniques in Nigeria,” in S.Leith Ross, Nigerian

Pottery Ibadan University Press

Unpublished notes, letters and diaries, consulted courtesy of

his son, Seth Cardew

- Aliyu,D 1980 “Nigerian Pottery Tradition and New Techniques,”

Pottery Quarterly

- Michael Cardew and pupils 1983 Catalogue: exhibition at York

City Art Galler

- Clark,G. 1978 Michael Cardew. London: Fabe

- Falconer, J.D 1911 the geology and geography of Northern Nigeria.

London: Macmillia

- Hallum, Alister 1974 Mud and Water Man BBC/Arts Council of Great

Britain (television program

- O’Brien,M. 1975 Abuja after Michael Cardew,” Ceramic Review

34

Quality of photos - The photographs are scanned

from the journal and enhanced as far as possible.

Also of interest: The Interpreting Ceramics

Michael Cardew Centenary Symposium. Includes several

articles on Cardew and an interview of Michael O’Brien by

Jeffrey Jones.

More Articles

|