Reprinted with kind permission of Saudi

Aramco World and the author.

Jun’s

palace is called Pabellón de las Artes. And what is

the connection?

Jun’s

palace is called Pabellón de las Artes. And what is

the connection?

We’ll have

to enter Jun’s Pavilion of the Arts to find out.

A massive iron door

slides open easily, and we enter a bright, spacious museum that,

in the distance, curves to the left, leaving the last part out

of sight.

Lining the walls

and filling the floor-space are more than a hundred ceramic

vases, jars, jugs, plates, oil lamps and chests, from the gigantic

to the diminutive. Gracefully shaped, colored and gilded, decorated

with intricate geometric, floral and calligraphic designs, all

are in the 14th and 15th-century style of the Nasrid period

when the Alhambra was built: the last 200 years of Muslim rule,

when the arts in southern Spain flourished as never before.

Anyone with an interest

in Andalusian history entering here would rub his eyes in disbelief

and delight. Nearly all these ceramic pieces are lusterware,

made by a complicated process that was gradually lost from this

land after 1492, when the Muslims were finally expelled from

Spain following the Christian conquest of the Kingdom of Granada.

|

|

Ceramics

with this transparent, metallic overglaze are called

loza dorada (“golden pottery”)

in Spanish, though, strictly speaking, the pieces may

be any of several tints—both silver and gold tinged

with green are common. The earliest lusterware was created

at the beginning of the ninth century in Basra and Chuff,

in what is now Iraq. Soon afterward, the artisans of

Samarra, 125 kilometers (75 mi) north of Baghdad on

the Tigris River, started to create large quantities

to supply the courts of the Abbasid Caliphate, from

India in the east to Al-Andalus —Muslim-ruled

southern Spain—in the west. The technique also

soon flourished in Egypt. From there, some two centuries

later, artisans of Al-Andalus learned enough to start

their own production, reaching their apogee of beauty

and sophistication in the period of the Alhambra. Ceramics

with this transparent, metallic overglaze are called

loza dorada (“golden pottery”)

in Spanish, though, strictly speaking, the pieces may

be any of several tints—both silver and gold tinged

with green are common. The earliest lusterware was created

at the beginning of the ninth century in Basra and Chuff,

in what is now Iraq. Soon afterward, the artisans of

Samarra, 125 kilometers (75 mi) north of Baghdad on

the Tigris River, started to create large quantities

to supply the courts of the Abbasid Caliphate, from

India in the east to Al-Andalus —Muslim-ruled

southern Spain—in the west. The technique also

soon flourished in Egypt. From there, some two centuries

later, artisans of Al-Andalus learned enough to start

their own production, reaching their apogee of beauty

and sophistication in the period of the Alhambra.

At first, lusters were

made by applying pure metals like gold, silver, platinum,

tin and copper—each for its distinctive color—to

fired and wholly or partially glazed clay (“bisque”),

which was then refired at a lower temperature. The resulting

combination of glaze base and metallic sheen enhanced

the lines and colors of the decoration. Later, the technique

was refined by using metal oxides, which were also applied

on top of the glaze base with a fine brush. (In a different,

far less expensive process, pigment-based lusters, developed

in the 19th century, often characterize commercial ceramics

and porcelains up to the present day.)

Jiménez explains his

Alhambran luster technique in his typically exuberant

fashion, which itself may be a legacy from the Moorish

past. “I’m in a constant dialogue with all

the elements of the cosmos: oxygen, earth, water, fire

and time…. The process consists in converting

metal into oxide and then oxide back into metal. Metal

plus oxygen produces oxide. So if we now remove the

oxygen from the oxide we added previously, we again

get metal—a luster. The Arabs had this down to

a fine art.”

Complex lusters, he

says, may require firing more than once—and some

as many as six times. |

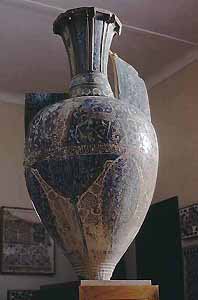

Very few examples of the old

lusterware have survived the last five centuries. One of the

most famous is the enormous, amphora-shaped “Alhambra

Vase” (also known as the “Vase of the Gazelles”),

and a replica of it is a centerpiece in this Pavilion. Were

I to make a guess as to how long it would have taken an artisan

of Al-Andalus to produce it and all the rest of these riches,

I would suggest a couple of lifetimes.

Wrong! They have all been produced

by one man, and he is alive and well, and full of energy and

ideas. Miguel Ruíz Jiménez is a short, bearded, powerfully-built

man in his mid-50’s. Said his wife, Ana, “He did

it all himself, with his own hands. And he built the Pavilion

as well. That alone took him 15 years!”

And

he’s filled his Pavilion only not with his art, but also

a huge studio, an auditorium and research facilities. A stone’s

throw away, he runs a small factory that employs 24 people to

produce the kind of decorative Andalusian pottery found in local

shops. It is a separate world from his Nasrid-style lusterware,

whose prices range all the way from € 100 to € 60,000

($120–$72,000).

And

he’s filled his Pavilion only not with his art, but also

a huge studio, an auditorium and research facilities. A stone’s

throw away, he runs a small factory that employs 24 people to

produce the kind of decorative Andalusian pottery found in local

shops. It is a separate world from his Nasrid-style lusterware,

whose prices range all the way from € 100 to € 60,000

($120–$72,000).

I thought a local Granada newspaper

had exaggerated wildly when it described Jiménez as “a

sketcher, welder, potter, wood carver, chemist, blacksmith,

painter, writer, architect, sculptor and artist.”

Jiménez likes to refer to what

he does as “alchemy.” In a way, this makes sense,

for the origin of the word is the Arabic al-kimiya’,

which connotes transmutation. This is particularly apt for the

lusterware, whose often golden color is achieved through a complicated,

even arcane process.

He has followed the authentic

Arab tradition in the making of Alhambran glazed pottery,”

says Ana Carreño, editor of El Legado Andalusí, a cultural

magazine based in Granada. His research is “serious and

accurate,” she says, “and his determination and

effort over 25 years has led to recognition here in Spain and

in the Gulf Arab countries through exhibitions, television programs

and workshops.”

Son of a simple granadino

potter, Jiménez got clay on his hands as soon as he could crawl.

By seven he was throwing pottery. What set his artistic passions

afire more than 30 years ago was the discovery of the sensual

loveliness of the old Andalusian art. “When I contemplated

the vases of the Alhambra, I decided that I wanted to do this,

and I started to research and study,” he says. The path

he took was very different from that of his father.

The task was gigantic: Jiménez

studied chemistry, and he visited Nasrid masterpieces worldwide.

There are, he says, no original, firsthand written sources.

From Nasrid times, only the bare names of a few ceramists have

been found—Suleiman Alfaqui, Sancho Almurci, Hadmet Albane,

Felipe Frances, Abdul Aziz, Abel Allah Alfogey. Of their techniques,

there is nothing.

In 1990, Jiménez published the

story of his research and struggle to recreate, experiment by

experiment, the period’s ceramics in a self-published

book titled The Epic of Clay. Here, his mystical streak

comes out in prose as florid as his Nasrid arabesques: “Formulae

and excessive pretension of technical precision are at times

superfluous,” he writes, “for meeting the complex

challenge of combining substance and space in pursuit of an

intuitive art and dreamed shapes when confronted by a series

of subtle factors, as unforeseeable, as variable, as those that

determine the tonality, texture, coloring, and metallic intensity

of the tones and, more specifically, what is going to be the

singular identity of the masterpiece.”

A little further on he writes

of the duende, the spirit or soul, required to make

lusterware. “We must feel intensely and with the greatest

profundity those indefinite factors that, although they take

us to a foreseen outcome, oscillate during the whole process

in a wide abyss of contingency.”

To recreate the Nasrid masterpiece

style, he found clays and minerals both locally and as far afield

as China, South Africa, England and France. Over four decades

he studied the materials, built Arab-style kilns and fired them

to reach temperatures up to 1040 degrees Centigrade (1904°F).

(Examples of Arab-type kilns can still be found in ceramics

centers such as Paterna and Manises.) For as long as anyone

knows, the potters of this region have used “mountain

wood”—thyme, rosemary and gorse—to achieve

high temperatures and just the right kind of smoke. Jiménez

used the same, varying his materials, varying his temperatures,

shifting the placements of objects inside the kiln.

He also taught himself to draw

the intricate calligraphy, “profuse and complex symmetry

of plant motifs, geometric stylizations, chain patterns, borders

and trimmings, stars, polygons” and more, all replicating

or inspired by Nasrid originals. One large vase, he explains,

has a surface area of two or three square meters (40 to 60 sq

ft) densely covered with designs that have to settle on the

curvilinear, irregular and multifaceted surfaces. Sketch after

sketch, drawing after drawing, rejection after rejection, it

may require as many as 300 or 400 drawings “with the corresponding

days and days of laborious work and continuous meditation.”

Then,

for a masterpiece like the Alhambra Vase, which weighs about

100 kilograms (220 lb) and stands 1.5 meters high(4' 10"), the

throwing is itself a process no less mind-boggling that may

take Jiménez as long asa month. During this time, the upper

part must never be allowed to dry out, lest it become impossible

to join with the other parts, while the lower parts must gradually

dry in order to support the weight of the top parts.

Then,

for a masterpiece like the Alhambra Vase, which weighs about

100 kilograms (220 lb) and stands 1.5 meters high(4' 10"), the

throwing is itself a process no less mind-boggling that may

take Jiménez as long asa month. During this time, the upper

part must never be allowed to dry out, lest it become impossible

to join with the other parts, while the lower parts must gradually

dry in order to support the weight of the top parts.

“You humanize the piece

with your hands,” Jiménez says. “You mark on the

vase your impressions of humanity and sentiment, mastery and

culture.” It was this attitude, he believes, that enabled

him to match the master craftsmen of Al-Andalus.

The more I looked into how Jiménez

works, the more I saw a spiritual dimension in his art. The

relationship between him and clay and fire, though based on

years of observation and science, incorporates at least as much

feeling and intuition, of the kind that comes from a master’s

understanding of each step along a complex path.

These days, Jiménez’s

meditations are broken most often by his cell phone, which interrupts

him with questions from customers, family, friends and foremen

in the factory. Watching him made me wonder where Michelangelo

would have got to had he possessed a cell phone.

In order to focus Jiménez’s

attention for a talk, we went to lunch—phone off—in

a popular village restaurant.

I

asked whether his large amphora-style vases were indeed exact

copies of known originals or his own designs. He explained that

it was a combination: “You have to assimilate the [known]

pieces, interpret them and then reconstitute, adding some of

yourself. It is like the construction of a building. There is

some cement, the basic knowledge. So you use the elements you

control to add something more. My approach is that if there

are elements I don’t know, I search for them,I learn them—or

I invent them.”

I

asked whether his large amphora-style vases were indeed exact

copies of known originals or his own designs. He explained that

it was a combination: “You have to assimilate the [known]

pieces, interpret them and then reconstitute, adding some of

yourself. It is like the construction of a building. There is

some cement, the basic knowledge. So you use the elements you

control to add something more. My approach is that if there

are elements I don’t know, I search for them,I learn them—or

I invent them.”

The initial firing of the pieces,

he explains, is one of the most difficult stages. His favorite

kiln for the big pieces is still the Arab, wood-burning kiln.

“In order to manage the atmosphere in the kiln,”

he says, “you have to know how the air functions and moves

in there, parameters, proportions, height, placement, and how

things work between the combustion chamber and the firing section.

When you fill the kiln, you have to place the pieces exactly

according to how you want them done, at the speed you want,

controlling with an opening below. To achieve an atmosphere

for firing properly, air should circulate with a minimum of

oxygen.”

And the smoke plays an important

part, too. “Smoke—I cannot explain it. You have

to know the interior of the kiln. You have to dream with it,

think about it burning. Then see how the piece turns out and

compare it with the previous piece. To get there in the end

is an interminable chain of study, trial, error and trial.”

Although

by now we know the answer to my question, I ask it anyway: “Could

you achieve an exact replica?”

Although

by now we know the answer to my question, I ask it anyway: “Could

you achieve an exact replica?”

Jiménez replies: “My question

to you is: What would that culture have been doing had it not

been for the horrible interruption 500 years ago, those horrible

wars? I could become a simple messenger from that time, or I

could continue to advance that richness, sensitivity and culture,

that discipline.”

What Jiménez achieved, as I

saw, were near replicas of great fidelity to the originals,

and occasional improvements. Many are his own designs. “I

copy, research, create an essence, and then at times I add something

from our time, but with all respect toward what those people

did 500years ago.”

Lunch is about finished. Jiménez

switches on his phone.It rings instantly. He answers, hangs

up, and it rings again. With an impatient expression, he switches

it off. “I’m going to get rid of this thing, and

my factory, and all the things that occupy too much of my time.

I want peace and quiet, time to create. That’s what I

was born to do. I need time to express what I have to express.”

As a final word, Jiménez says, “I hope others lean on

what I have humbly done and move ahead.”

|

Tor

Eigeland (www.toreigeland.com)

has contributed writing and photography to Saudi Aramco

World for more than 30 years. He lives near Toulouse,

France.

|

Contact:

Pabellón de las Artes

Cruce de Jun-Alfacar

18213 Jun-Granada, Spain

Tel: +34 958 414 077

Fax: +34 958 414 112

Email: comercial@miguelruizJimenez.com

www.miguelruizJimenez.com

www.abacoarte.com

This article

appeared on pages 2-9 of the January/February 2006 print edition

of Saudi Aramco World.

© Saudi

Aramco World