|

More

on Paperclay

by

Graham Hay

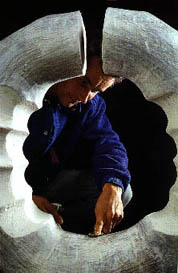

Because of the rapid drying of dry-to-dry joins, and the strength

of unfired paperclay, walls cannot only be built upwards but also

horizontally and downwards. After building a dry rod frame, I build

inwards, outwards, downwards or upwards from it by rods, planes

or spheres. The base frame can be a single vertical sheet, a cone,

a cube of planes or rods, or any other form. For joining two curved

dry surfaces, I use plastic paperclay dipped in paperclay slip to

increase the contact surfaces and strength of the join. I anticipate

unusual forms as others also gain control over these multi-directional

building techniques. Wool thread or string can be soaked in paperclay

slip, allowed to dry completely before re-soaking it again. Three

or more soaking/drying cycles create a good sized rod. This is a

quick way to build strong straight or curved rods, rather than rolling

them out. They can be cut by scissors to the desired length for

building. Alternatively, while plastic, these string clay rods can

be draped over a form to dry in curving lines. More recently, I

have rolled out or cut slabs into tapered rods of plastic paperclay

which are bent into curves and spirals before drying. These can

be then 'spot-welded' with slip from a squeeze bottle to form supports

or decoration for delicate objects.

Having used paperclay for more than four years, increasingly I find

myself considering sources of paper and its role in our lives. Despite

the promise of an electronic society, the computer has increased

the volume of paper we handle daily: our weekend newspaper now boasts

more than 432 pages of news and advertisements. Similarly, the annual

distribution and recycling of yellow and white phone books creates

a mountain of paper. Without paper, our whole administration and

knowledge systems would collapse. More specifically, for artists,

paper is essential. Apart from increasing the strength of a clay

body, paper underpins most artistic practices; we use it to record

ideas, design and record our ceramic work, as well as do our accounts

and correspond with customers, galleries and shops. Similarly, the

documentation and organisation of exhibitions involves a huge amount

of paper for invitations, grant applications, press releases, catalogues

and posters. In two dimensional art practices, such as printing

and painting, contemporary art simply would not exist without paper.

How many of us have a small home library of books and journals such

as Ceramics: Art and Perception? We line our homes and offices with

masses of paper as if we are creating paper nests or cocoons. Even

when recycling paper into my paperclay, I could not keep up with

the paper tide, so when a local paperclay became available for conventional

clay prices I began to create paper sculptures. After stacking the

paper I drilled, cut, carved, sanded and bound it. Following this

experience, I began to see paperclay as a solid material that we

can shape and refine into different forms before finally assembling

the dried pieces into a completed work.

Having used paperclay for more than four years, increasingly I find

myself considering sources of paper and its role in our lives. Despite

the promise of an electronic society, the computer has increased

the volume of paper we handle daily: our weekend newspaper now boasts

more than 432 pages of news and advertisements. Similarly, the annual

distribution and recycling of yellow and white phone books creates

a mountain of paper. Without paper, our whole administration and

knowledge systems would collapse. More specifically, for artists,

paper is essential. Apart from increasing the strength of a clay

body, paper underpins most artistic practices; we use it to record

ideas, design and record our ceramic work, as well as do our accounts

and correspond with customers, galleries and shops. Similarly, the

documentation and organisation of exhibitions involves a huge amount

of paper for invitations, grant applications, press releases, catalogues

and posters. In two dimensional art practices, such as printing

and painting, contemporary art simply would not exist without paper.

How many of us have a small home library of books and journals such

as Ceramics: Art and Perception? We line our homes and offices with

masses of paper as if we are creating paper nests or cocoons. Even

when recycling paper into my paperclay, I could not keep up with

the paper tide, so when a local paperclay became available for conventional

clay prices I began to create paper sculptures. After stacking the

paper I drilled, cut, carved, sanded and bound it. Following this

experience, I began to see paperclay as a solid material that we

can shape and refine into different forms before finally assembling

the dried pieces into a completed work.

I also considered our local use of clay as a building material.

Because of wood-eating white ants, most of our old buildings and

modern houses are made from ceramic bricks. So along with the necessary

paperwork these brick buildings shape how architecture is organised

and presented. Consequently I began to make tiny paperclay bricks

which, when dry, I joined together into organic forms. For me, these

were more about creating internal spaces than external forms, that

is, the public and private spaces in which we and art exist. Ceramic

art has a number of clearly defined schools of aesthetics arising

from cultural influences and from the physical properties and limitations

of the material. Paperclay enables the artist to use traditional

ceramic building techniques as well as skills borrowed from elsewhere.

Consequently the work can mimic many of the forms created in these

materials. However, we already have a tradition through ceramists:

Henry Pimm (1980s), Richard Notkin and Adrian Saxe, who create ceramic

objects which imitate wood or metal objects. The fundamental difference

here is process rather than imitation, for paperclay enables us

to easily create this type of work with some expertise. If paperclay

removes the clay skills necessary to create these illusions, does

this necessarily alter the significance of these artworks and traditional

ceramic skill hierarchies?

Next

Page > New Possibilities > Page

4

More Articles

|