Anne

Hirondelle knew soon after she had started law school that it

was a mistake, but she finished out the first year and then

immediately enrolled in the BFA program at the University of

Washington in Seattle, earning her degree in 1976. Hirondelle

already had a BA in English and an MA in Psychology, but with

the BFA she found her true calling and she has been a full-time

artist ever since. However, that instinct for clear thinking

and logical presentation which initially enticed her to law

school remains in her art. Her work reflects the direct vision

that a clearly-written law brief exhibits.

Anne

Hirondelle knew soon after she had started law school that it

was a mistake, but she finished out the first year and then

immediately enrolled in the BFA program at the University of

Washington in Seattle, earning her degree in 1976. Hirondelle

already had a BA in English and an MA in Psychology, but with

the BFA she found her true calling and she has been a full-time

artist ever since. However, that instinct for clear thinking

and logical presentation which initially enticed her to law

school remains in her art. Her work reflects the direct vision

that a clearly-written law brief exhibits.

When I first encountered Hirondelle’s work 10 years ago, she

was using the diptych format. The pairs of vessels were straight,

formal and hieratic, sitting on a wooden tray which acted as

a plinth for the architectural elements. Each piece was a frozen

still life, best seen from a single perspective. Move one of

the elements and the balanced drama was off kilter. However,

even though the overall effect was cool and disciplined, the

tableaux were not necessarily self-contained. The elements of

the diptych were vessels and the vessels had handles which,

by their nature, invited touch and involvement. They also suggested

function and with function comes human participation.

Over the years, the idea of two equal parts has been modified.

First the elements of the diptych became unequal: sometimes

the two parts consisted of a dominant vessel and subsidiary

base, sometimes vessel and lid. In her most recent exhibition

at The Works Gallery in Philadelphia the various parts have

merged into a single tall unity which Hirondelle calls “aquaria”,

the Latin word for ewer.

“The vessel has always been the core metaphor for my work,”

says the artist. “These particular forms have grown from the

plant forms that surround me in my perennial garden. Women have

been the traditional waterbearers of many cultures,” reflects

the gardener as she remembers the hours she has taken water

to cherished blooms. In ancient times it was the women who fetched

water for the family. Rebecca at the well in the Old Testament

is only one of many examples.

Hirondelle

lives in Port Townsend, Washington, a beach community of rocks,

not sand, that is close enough to Seattle to share the city’s

cultural advantages, yet far enough not to be a bedroom community.

It is home to one of the country’s most successful publishers

of poetry, Copper Canyon Press, whose founder is one of Hirondelle’s

closest friends. Both the editors and poets often drop in on

her. This easy companionship with poets is telling in her work.

Poetry is about nuance. It is finding just the right shade of

meaning or specific verb to describe a universal feeling. If

the word has too many syllables for the music of the line, it

is jettisoned and a new word must be found. This constant refinement

is also a hallmark in Hirondelle’s work.

Hirondelle

lives in Port Townsend, Washington, a beach community of rocks,

not sand, that is close enough to Seattle to share the city’s

cultural advantages, yet far enough not to be a bedroom community.

It is home to one of the country’s most successful publishers

of poetry, Copper Canyon Press, whose founder is one of Hirondelle’s

closest friends. Both the editors and poets often drop in on

her. This easy companionship with poets is telling in her work.

Poetry is about nuance. It is finding just the right shade of

meaning or specific verb to describe a universal feeling. If

the word has too many syllables for the music of the line, it

is jettisoned and a new word must be found. This constant refinement

is also a hallmark in Hirondelle’s work.

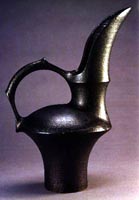

Her current body of work is remarkably consistent. Each piece

is dipped in the same soda ash glaze and fired to the same temperature.

They look metallic with an occasional freckle of crust on their

skin. The forms – the aquaria – are also consistent, all springing

from the same columnar base that flares into a full skirt. However,

the subtleties reveal themselves with a closer reading. Sometimes

the neck is only a choker wide before the spout takes over.

Sometimes it stretches as long as the throats of the African

women who wear copper coils to extend their necks. And the oversized

spouts have individual personalities. One is perpendicular and

resembles an old-fashioned coal scoop. Others are angled into

the same neck-thrusting motion of an egret or a crane. Several

have a slightly inward curling lip such as the large petal of

a calla lily. Even though the pieces are all watergivers, some

of the spouts look as though they would be awkward for

pouring, their strong personalities getting in the way of easy

function.

To balance the exaggerated spouts, the handles either make

a circle or follow the more gradual profile of a flying buttress.

Aesthetically they keep the ewer from tipping forward by being

the weight on the other end of the pulley. They are the counterpoint

to the strong forward motion. Many have thumb rests for

easier gripping. But when put to the test, these aquaria are

too large and massive to use. They are made of thick-walled

stoneware and when filled with water, they would be quite heavy.

Better to enjoy them as three dimensional design rather to take

their function literally. Each aquaria belongs in a place of

honour where it can be given poetic licence to be conceptual

rather than actual water bearers.

Gretchen Adkins is a writer on the arts from

New York, NY. Caption title page: Aquaria #36. 1997. 68 x 32.5

x 29 cm. Photographs courtesy of Garth Clark Gallery, New York.

More Pots of the Week