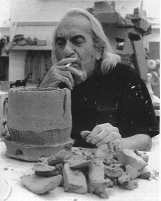

Peter

Voulkos touched clay, then he touched us. He journeyed

through life, and work, guided by his intuition, his past experiences,

and the curiosity to discover the next possibility. The 19th

century realists suggested that we are products of our heredity

and environment. Emile Zola proclaimed 'I am an artist. I am

here to live out loud' and Peter Voulkos did.

Peter

Voulkos touched clay, then he touched us. He journeyed

through life, and work, guided by his intuition, his past experiences,

and the curiosity to discover the next possibility. The 19th

century realists suggested that we are products of our heredity

and environment. Emile Zola proclaimed 'I am an artist. I am

here to live out loud' and Peter Voulkos did.

Voulkos lived a courageous life, he lived it with sincerity,

passion, integrity and respect. The magnitude of his accomplishments

and the revolutionary vision of his work will remain in the

museums and collections throughout the world and will be studied

by students indefinitely. No less important is the direct effect

he has had on those who were a part of his life, the way he

influenced them, and the accomplishments they have had and will

continue to have. Voulkos was the father of a movement that

is still in its infancy; it has only begun to be characterised.

Its history continues to unfold in the works and deeds of those

whom he inspired.

Since 1999, I have had the opportunity to work with Voulkos.

I assisted him in the construction of 16 major stacks, one of

which is more than 2.1 m (7 ft) tall. We also worked together

on numerous plates as well as a monumental ice bucket titled

Gaudi. Throughout this involvement, we were together for nearly

six months, from morning until night. I was with him during

his last days, and it is from this perspective that I write

about this legendary man and his creative process.

My first encounter with Peter Voulkos' work was in 1984. I

was delivering work for one of my teachers from the Kansas City

Art Institute, to a Chicago art gallery. On exhibit was a Voulkos

piece called Two Brick Stack. I slept next to it for three nights.

I traced every line, texture, movement and moment of that remarkable

piece. This was my first art experience; the first time I realised

the power of sculpture. I asked myself, What kind of man could

and would make this piece? Eighteen years later, and I am still

finding out.

I met Voulkos in his home in the early '90s, subsequently

firing three stacks and several plates in my Denver anagama,

meeting and corresponding occasionally. During this same period

of time, I was also fortunate to develop a friendship with another

artist, Jun Kaneko and, in late 1998 a phone call from Jun changed

my life. He called to tell me that he was inviting Peter Voulkos

to his Omaha, Nebraska, studio to make some new work and did

I know anyone that would be able to assist him. I immediately

answered yes me. I suggested that we do a workshop together

in Ohio, where I was teaching at Bowling Green State University,

in order to see if we would work well together. The Bowling

Green workshop took place in 1999 and the project in Omaha took

place the following summer at Kaneko's studio.

For me, the chain of events was magical. Everything fitted

together when we worked on a piece; we hardly needed to talk

about where the piece was going. Voulkos made all of the aesthetic

decisions and I tried to anticipate where he was headed. I wanted

to give him whatever support I could. All of the work that we

made together followed a similar procedure. We would throw a

number of parts on the wheel: plates, cylinders, thick bars

all raw materials for the fabrication process (a 'dance'

may be a more accurate description) that ensued.

I came to discover that Voulkos' creative process was quite

different than had been previously described by art historians.

For instance, writers have tended to overemphasise the aggressive

hack and slash, take no prisoners approach to his work. Violence

and machismo were not a part of what I saw in the work or the

man. When Voulkos touched the clay there was no ego, only courage.

His knowledge of the material was complete; he knew how to work

with and through it. I noticed that when we were working together,

it became a series of movements that took place through a kind

of protracted moment in time. It was a much slower dance than

one might guess. As Voulkos initially began to touch the clay,

he also began to improvise, responding to the moment, conscious

of the past but always moving forward. I cannot remember him

ever second-guessing himself he would move over every

area of the piece with care and vigilance, constantly tuned

in to what was happening with the clay. Over the course of a

work session, he would come to a point of saturation. It seemed

that the clay and his body always needed a break at the same

time.

After working, when his mind had time to digest it all, he

would begin to think about where the piece might go tomorrow.

Often, he would tell me in the morning over coffee that he had

been dreaming about the piece all night, saying ³I know

what I am going to do with that neck.² After a day of work

at Jun Kaneko's studio, we would go up to our apartment,

make a couple of Bloody Marys and watch the video of what we

had made that day. It was like he was a coach reviewing a game

film only much funnier. During the video he would see

things that he couldn't see while in the middle of making

the piece. It was fascinating to him (and to me) to see the

way the eye of the camera was able to capture different information

than he was, seeing it all at the same time.

Continue