| The Last Water Jar

By Jim

Danisch.

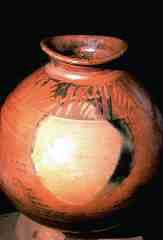

Lightning

strikes dirt, blindingly fusing it into nature’s terra cotta,

changing its color to red, brown, orange, white, gray or black,

sometimes leaving behind strange fused bits of metal that are sought

as amulets. Potters have simulated and controlled this process since

before memory. The names for the parts of a pot -- lip, mouth, neck,

shoulder, belly, underbelly, foot -- are imbedded in the beginnings

of language. Although we have lost its everyday presence in our

electronic culture, the archetypal water jar is deeply integrated

our collective unconscious, and is remarkably similar around the

world, whether it is uncovered in an archaeological excavation in

Peru or in the street market in Kathmandu. Its nature is round or

ovoid, shell like, formed to meet hip or head, stretched as thin

as the clay permits the maker, fitted with a neck and mouth that

leads to a dark womb interior, and of a size that women can carry

comfortably. It is always unique to the neighborhood where it is

made – easily recognizable by its form and the way it resonates

sound. When it is gone from a culture, it means the extinction of

yet another simple function that brought people together in the

closely woven social net typical of the pre-industrial world. Lightning

strikes dirt, blindingly fusing it into nature’s terra cotta,

changing its color to red, brown, orange, white, gray or black,

sometimes leaving behind strange fused bits of metal that are sought

as amulets. Potters have simulated and controlled this process since

before memory. The names for the parts of a pot -- lip, mouth, neck,

shoulder, belly, underbelly, foot -- are imbedded in the beginnings

of language. Although we have lost its everyday presence in our

electronic culture, the archetypal water jar is deeply integrated

our collective unconscious, and is remarkably similar around the

world, whether it is uncovered in an archaeological excavation in

Peru or in the street market in Kathmandu. Its nature is round or

ovoid, shell like, formed to meet hip or head, stretched as thin

as the clay permits the maker, fitted with a neck and mouth that

leads to a dark womb interior, and of a size that women can carry

comfortably. It is always unique to the neighborhood where it is

made – easily recognizable by its form and the way it resonates

sound. When it is gone from a culture, it means the extinction of

yet another simple function that brought people together in the

closely woven social net typical of the pre-industrial world.

Symbolically, the potters’ wheel as great god Vishnu’s

discus spins out the Hindu creation myth. As the universe was set

in motion, so is the soft clay first spun to the center of the wheel,

the primordial still point, where it naturally assumes the shape

of a linga -- the male principle. Next the potter opens a yoni --

the female principle -- which is shaped like a womb and will become

pregnant with the potter’s creative energy. After this marriage,

he can birth any form. When held to the ear, water jars tell the

story of human endeavor on earth: the sound is like surf, complete

with echoes of gossip at the well, satisfied chatter in the kitchen,

warfare and suffering, great music and overheard intrigues. In Southeast

Asia, every village household still keeps a water jar -- the water

stays cool without refrigeration, is freshened by some mysterious

alchemical effect of the clay, and remains one of the few ritualized

connections to the past. The element water along with its container

have a major role in most religions.

I’ve

been involved with Asian potters since 1979; as a potter myself,

I’ve learned to listen to the song of the water jar from these

unassuming people, who live in villages that resonate every morning

to the sound of hundreds of pots being beaten into form by craftspeople

who know precisely when the pot is finished by the sound it produces.

In particular, I work closely with Tharu (“Tah-roo”)

people, a large and very old ethnic group in the lowlands of southern

Nepal. Nobody knows their origins. When the government of Nepal

eradicated malaria in the 1950’s, freeing up thousands of

square miles for agricultural use (and inevitable deforestation),

most of the Tharus, who had no system of land ownership, were disenfranchised

when “their” land was distributed as political favors.

These northerners cut down the jungle, worshipped different gods,

and claimed land that the Tharus, in their innocence, never knew

could be owned. The area is called Deokhuri, and is ruled benevolently

by a feudal Lord who lives in a rambling stucco palace with at least

70 extended family members and retainers. It is the same scale as

the palace in which the Buddha was raised, just two days' walk from

here (and about four hours by car, if the roads were ever in good

condition). I’ve

been involved with Asian potters since 1979; as a potter myself,

I’ve learned to listen to the song of the water jar from these

unassuming people, who live in villages that resonate every morning

to the sound of hundreds of pots being beaten into form by craftspeople

who know precisely when the pot is finished by the sound it produces.

In particular, I work closely with Tharu (“Tah-roo”)

people, a large and very old ethnic group in the lowlands of southern

Nepal. Nobody knows their origins. When the government of Nepal

eradicated malaria in the 1950’s, freeing up thousands of

square miles for agricultural use (and inevitable deforestation),

most of the Tharus, who had no system of land ownership, were disenfranchised

when “their” land was distributed as political favors.

These northerners cut down the jungle, worshipped different gods,

and claimed land that the Tharus, in their innocence, never knew

could be owned. The area is called Deokhuri, and is ruled benevolently

by a feudal Lord who lives in a rambling stucco palace with at least

70 extended family members and retainers. It is the same scale as

the palace in which the Buddha was raised, just two days' walk from

here (and about four hours by car, if the roads were ever in good

condition).

Almost out

of

sight,

snow peaks shine --

horizon mounted mirages

far from the valley footpaths of gravel and clay

Bare feet treading Himalayan debris

spewed by monsoon torrent

charging to the Ganga

“We can walk to India in one day

and we know about camels in Rajasthan”

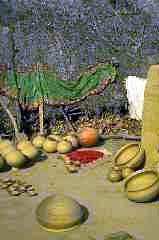

Over 600 potters live in this wide valley, in long, thatched houses

that appear to be rooted in the ground -- their roofs come down

so low -- semicircular door openings breaking the edge. Men must

stoop down to enter the cave-like dark of the interior. At the end

of the rainy season, the houses are camouflaged by rampant squash

vines, which supply both shade and nourishment, and are safely out

of hungry animals' reach. So much are they of the earth, villages

create only a small textural anomaly on the vast expanse of flood

plain, complex in its drainages and forests and fields.

Nobody

in the valley can remember when they were not potters. They continue

to provide the necessary ceramic containers for this old culture

that spreads over Southwestern Nepal and into northern India. These

people call themselves Tharu, and lived for centuries as a nondestructive

part of the lowlands ecology, their population held in balance by

climate and disease. Each Tharu house has a special alcove for the

gods. There are clay horses and there is the first clay man. Nobody

in the valley can remember when they were not potters. They continue

to provide the necessary ceramic containers for this old culture

that spreads over Southwestern Nepal and into northern India. These

people call themselves Tharu, and lived for centuries as a nondestructive

part of the lowlands ecology, their population held in balance by

climate and disease. Each Tharu house has a special alcove for the

gods. There are clay horses and there is the first clay man.

The landscape appears simple and flat when seen from a distance

-- its horizon articulated by surrounding low hills and distant

hints of snow peaks. But walking through it is indirect, diverted

by unforeseen complexities of waterways, rice plantation and bamboo

groves, which curve the road around all the places a man cannot

walk. Dirt tracks, dug with simple hand tools and maintained by

village volunteers as a form of direct taxation, are smoothed by

the feet of humans and animals, and in recent years, a couple of

motorized vehicles a day. Large herds of bullocks are sent out every

morning to graze and produce dung -- a valuable multi-purposed substance

used for fertilizer, architecture and fuel. Fresh cow dung contains

albumin -- an excellent glue and binder -- and fiber, both of which

contribute to the strength and water resistance of mud applied to

the woven reed mats that define house walls. At “cow time”

every evening, the herd returns with its cloud of dust.

Sometimes dust and sometimes mud.

Wattle and daub, clay and cow dung

shape the architecture

in fluid, hand-smoothed planes

Earth and water determine the swelling

shape of the pots

as they provide

the medium for crops

Clay lies in the stream crossings

thick and clinging

Brilliant reflections

hot sun, steamy fields

outlined by earthen dikes

Squash on thatch

Entering a Tharu long house requires bending low, but once inside,

there is a feeling of spaciousness, reaching up to the darkness

under the peak of the roof. The space is divided sculpturally into

bedrooms, kitchen and storage, by monumental clay and cow dung grain

containers that grow from the floor up to head height. In the dark

interior, they have the presence of guardians. Above these, bunches

of hanging objects punctuate the dark -- baskets, dry corn, implements

that in their unfamiliarity stimulate imagined purposes.

Inside it is dark

the rafters are hung heavy with

pottery and

baskets and

mysterious dark packages

all at different

levels

ascending into the deepest dark

which gathers under the thatched crown

What is it?

“Oh -- we keep things in it.”

What things?

“You know – our own things…”

Varying amounts of food, work, rest, water, ritual and alcohol

are the main features of everyday life. Whether Tharus live or die

depends on the grace and power of their gods, who, like Nepal itself,

are stressed by the increasing number of evil spirits and foreign

devils that are entering their world. Darkness is kept at bay just

outside the village boundary, where the guardians’ shrine

stands outside a mango grove. It is activated by the frequent cycles

of ceremony that are necessary to keep the universe in balance.

Earth, water, fire, air and space -- the makings of a water jar

and a universe.

Strong-backed

women balancing jars on their heads gather at the well with its

four corner posts, carved as deities, gossiping while they wait

their turn to run the bucket down on its rope. Gods control both

water and gossip; perhaps water jars carry the gossip home to whisper

it from their seats in the earthen floor to the cooking fire in

its clay tripod. Squatting, the women feed the fire and stir the

terra cotta cooking pots. These pots are only made by women; they

form them without a wheel, in ritual unison, at the same time of

year, and fire them in their back yards. At meal time, the rice

tastes of smoke and talk. Strong-backed

women balancing jars on their heads gather at the well with its

four corner posts, carved as deities, gossiping while they wait

their turn to run the bucket down on its rope. Gods control both

water and gossip; perhaps water jars carry the gossip home to whisper

it from their seats in the earthen floor to the cooking fire in

its clay tripod. Squatting, the women feed the fire and stir the

terra cotta cooking pots. These pots are only made by women; they

form them without a wheel, in ritual unison, at the same time of

year, and fire them in their back yards. At meal time, the rice

tastes of smoke and talk.

As sharecroppers forced to give half the crop to their Lord, men

must earn more rice by making pottery as much as possible, using

enormous wheels shaded by small huts. This is how to make a potters'

wheel: Start by crossing two timbers of sal wood, hard and heavy

and four feet long. Wrap split bamboo around this cross to make

a circle. Then mix clay, straw, rice hulls, cow dung, goat hair

and molasses to form the great disc.

If

you wait a year or two, one of the fast-talking traders who has

been with the wild men in the mountains will pass by, bringing rare

and wonderful things. They know a place in the high valleys, where

Vishnu has caused round black stones to be found in the river bed.

As the mountains come sliding and crashing down each rainy season,

the irresistible monsoon-swollen river carries, crushes and sorts

whatever it swallows -- mountain fragments, rocks, Vishnu's discus,

ancient and recent dust -- and tumbling black saligram stones. When

cracked open, they reveal Vishnu's spiral, as the positive and negative

of a fossilized snail shell, resurrected from its incalculably old

seabed, shoved up by Indian as it plows under China. If

you wait a year or two, one of the fast-talking traders who has

been with the wild men in the mountains will pass by, bringing rare

and wonderful things. They know a place in the high valleys, where

Vishnu has caused round black stones to be found in the river bed.

As the mountains come sliding and crashing down each rainy season,

the irresistible monsoon-swollen river carries, crushes and sorts

whatever it swallows -- mountain fragments, rocks, Vishnu's discus,

ancient and recent dust -- and tumbling black saligram stones. When

cracked open, they reveal Vishnu's spiral, as the positive and negative

of a fossilized snail shell, resurrected from its incalculably old

seabed, shoved up by Indian as it plows under China.

Potters’ wheels are manifestations of Vishnu, the union of

yoni and linga, the turning circle, the center and the circumference,

bound into unity by cow dung. This is a heavy load of symbolism

to turn around, and the wheel properly has one of these saligrams

as the pivot stone.

Make a stake of ironwood, broad at the base to bury in the earth,

and pointed at the top to spin the saligram. Set in place and turned

with a stick placed in a depression on the circumference, this giant

top is ready to defy gravity for long minutes. The potter has magic

in his stick, whipping the wheel off the ground -- Vishnu’s

discus that spins his lump of mud into the world of hollow singing

forms.

The seasonal pulse of agriculture coalesces energies. When fields

are dry, men dig clay and make pots to trade for rice, which is

eaten or preferably, made into beer for breakfast. If there is enough,

the beer is distilled into rakshi to blur hard reality a bit more.

When the fields are wet and pots won’t dry, men wait for the

rice to grow. Women work all the time. When a stranger comes, they

hide inside the house with their babies.

“Our life is like this:

Hard when we plow the ground

hard to persuade the seeds to grow

hard when we have no money,

on the road, trading clay

pots for rice

peddling empty water jars

for full belly

in the monsoon waters we live on an island

sailing on brown floods

rolling boulders shake our houses

the river eats our land

Rice greens the full flooded paddies

but our plates are empty

little sister

gets sick and dies

The doctor went to Kathmandu

he doesn’t like the monsoon

We have nowhere to go.

When the crops come in

full stomach, maybe

We sit in the winter sun

sit in the dusty courtyard

Play with the children

Today there’s rice to make beer

to drink in the afternoon

A man can touch the gods

just enough to persist in

being a man”

Sun

dissolves the chilly dense fog of early morning, with its cloaked

figures walking barefoot on their morning errands. Drumming begins

outside the pottery-making houses, as yesterday's half-formed pots

are expanded into their final globular resonant shapes with wooden

paddle and terra cotta anvil, some of them fully as big as the men

who drum their forms, expanding the clay until it is stretched as

thin as the shell of an ostrich egg. Water jars are never empty:

when they are not holding water, they contain sound; each standard

shape having its own resonant frequency, as if the potters scattered

throughout the village tune their jars to each other. After years

of use, the mushroom-shaped clay anvils that hold the curve against

the wooden paddle are as shiny as mirrors. In the Hindu creation

myths, sound was the first manifestation of the sentient world. Sun

dissolves the chilly dense fog of early morning, with its cloaked

figures walking barefoot on their morning errands. Drumming begins

outside the pottery-making houses, as yesterday's half-formed pots

are expanded into their final globular resonant shapes with wooden

paddle and terra cotta anvil, some of them fully as big as the men

who drum their forms, expanding the clay until it is stretched as

thin as the shell of an ostrich egg. Water jars are never empty:

when they are not holding water, they contain sound; each standard

shape having its own resonant frequency, as if the potters scattered

throughout the village tune their jars to each other. After years

of use, the mushroom-shaped clay anvils that hold the curve against

the wooden paddle are as shiny as mirrors. In the Hindu creation

myths, sound was the first manifestation of the sentient world.

Sun dries the clay. A group of pots is beaten in several stages

during a day, as the form slowly stiffens into finality.

Drying

pots are moved in and out of the sun for several days: into the

thatched pottery hut at night to protect them from dew, and back

out each morning, until there are enough to make a firing -- usually

several hundred pieces ranging from small water or rakshi pots about

seven inches in diameter, up to the big storage pots that may reach

two feet or more. Although the function, size and proportions of

each pot are standard from village to village, decoration identifies

the pot’s origins. Some villages impress designs with the

end sections of reeds, others make simple stippled bands; the most

elaborate are finger painted by the women. Drying

pots are moved in and out of the sun for several days: into the

thatched pottery hut at night to protect them from dew, and back

out each morning, until there are enough to make a firing -- usually

several hundred pieces ranging from small water or rakshi pots about

seven inches in diameter, up to the big storage pots that may reach

two feet or more. Although the function, size and proportions of

each pot are standard from village to village, decoration identifies

the pot’s origins. Some villages impress designs with the

end sections of reeds, others make simple stippled bands; the most

elaborate are finger painted by the women.

On the day of the firing, the pieces are coated with a shiny,

thin clay slip known as “gabij”, which adds beauty to

the surface and can be used for finger painting. This is the same

technology that was used all over the world before glazes were developed.

We are most familiar with it from Greek and Roman pottery. The process

of transforming clay back into stone is alchemical; firing is a

time of excitement and tension for potters in any country or historical

period. Even with modern state-of-the-art technology, there is still

mystery around what happens inside the kiln; too hot to feel, too

bright to see. The fire is managed, but not trustworthy. There is

always the potential of the fire getting out of our control and

destroying days of work. The fire master's job is a crucial one,

and he works with a combination of experience, magic, guesswork

and good hunches, tuning his intuition to the sound and subtle cues

of escaping moisture and quality of smoke.

The floor of the communal firing house is layered with these great

brittle shells of clay, systematically stacked in an oval heap that

may be twenty or thirty feet in diameter and three to four feet

high, packed in the interstices with firewood. Miraculously, men

can walk on the load, as they cover it over with a mixture of clay

and straw. The result is a shiny, wet low mound which occupies most

of the firing house, waiting for the fire to dry it into a hard,

cracked crust at the end of the firing.

As with all transformative events, a ritual offering is made to

the fire gods, and the officiating potter walks around the huge

stack, drawing a line in the clay circumference with his four fingers

-- this is to prevent the entry of malevolent spirits that can and

frequently do destroy pots. The fire is started from one side, and

by periodically opening vent holes with a pole, is guided inside

what looks like the world's biggest pie crust. A large firing may

take two days. The fire master dozes on a string bed by the firing,

waking every few hours to make more vent holes. The heap smokes;

now and again the crust breaks, revealing the red glow of embers

and seemingly transparent glowing walls of pots. These gaps are

covered by large floppy discs of clay and straw to conserve the

heat. The process is slow and deliberate, in keeping with all time

in the Tharu culture. Eventually, the fire has moved across the

heap and used up all its fuel. The pots cool for half a day.

“No need to rush

the fire

It moves

at its own rate

and decides the fate

of our pots and our bellies

both empty waiting to be filled”

At the time of unloading, everybody comes to see if the fire gods

were cooperative. It is usual to lose up to half of the products

in firing, depending on the vagaries of drying, wind, firewood,

and whatever stray or malignant spirits came wandering by. Call

the shaman to cure the problem; he knows the science of cause and

effect.

“He will talk with the spirits

and ask them

to maintain the wind in our pots

...we are poor people...

without the wind

there would be no song in our hearts”

In the open spaces in the village, stacks of identical water jars

identify potters’ houses. Identical until you go to choose

one. The curves differ by millimeters; surfaces have been colored

by the fire’s tongue; but even in the dark there is one pot

that will stand out, perhaps because of its special resonance. Pots

in the market are tapped to make sure of their resonance: a cracked

pot sounds dead. But this is not the resonance I am getting at.

It is not a quality you can measure with an instrument: call it

magic, or devotion -- the product of a moment of synchronicity in

the potter’s life when all his skills, the weather, the mood

of the day, and the five elements came together in a small epiphany.

As summer approaches, the heat builds for weeks, each day's tension

forming clouds, which fail to bring relief, except for occasional

disastrous winds that carry only enough rain to frustrate hope and

destroy firings. Finally, the sky swells with water from the South

and dumps it in great floods on the barren fields. Gratefully, the

people plant rice, which greens the valley floor, thriving on monsoon

fecundity.

"World of muck and green

struck by the sun bursting

through dark sheets of hard-hitting rain

boiling black sky"

The deluge persists during three months of skyburst when virtually

no work can be done. The roads are impassable, disease strikes,

and the people subsist on one bowl of rice gruel per day while the

water swells the next crop. At last the time of feasting comes,

followed by clay gathering and a renewal of the rhythm of pot making.

In the time that started before memory, the Rapti River has meandered

over the Deokhuri Valley in unpredictable ways -- every one hundred

thousand years there is a cataclysmic flood that takes everything

with it down to India; perhaps every ten thousand years it deposits

an exceptionally well-ground layer of fine, plastic brown clay.

Every year, there comes silt and gravel. In recent years, clay is

found about ten feet underground in the flood plain, in a layer

that ranges from 1 to 3 feet deep. In the annual cycles of renewal,

the river regularly takes a village and its farmland, forcing the

people to squat in new areas, which are becoming very scarce.

Every year, the potters must dig through the monsoon’s mud

and silt deposits to this layer, and carry it to their villages

-- a walk of 1 to 3 hours, using a pole over the shoulders with

two baskets hanging from the ends. The clay is soaked with water,

kneaded by foot, and made into a mound half as tall as a man. The

mound is covered with sand, which is wet down with water, and sits

like a large, living presence in the dark shade of the workshop.

It takes six days to prepare a ton of clay. This is the season of

Dasain or Durga Puja, which requires the biggest feast cycle of

the year, and the entire village, from grandparents to grandchildren,

is busy making pots and loading them in the communal firing house.

New water jars and small clay horses -- household deities -- are

a necessary part of the celebrations: they must be renewed each

year and installed ritually.

When there are enough pots, half the village goes on the road.

There is limited local demand, so the potters walk long distances.

To walk from Deokhuri over the hills north to Dang takes two days.

It is where hill people come to trade, and among other purchases

they carry pots up the mountain. The potters could go by bus, but

either they do not have the necessary few rupees, or they claim

that breakage is high, or they simply never do things that way.

Instead, you can see groups of them, carrying as much as possible.

Men with their carrying poles, women with stacks on their heads.

If you calculate the costs, they do not earn their own labor. But

they need the small amount of cash they can earn to buy salt and

oil, and they come back with bags of rice. It may be that the hard

work and fun of going to the bazaar together is reward enough for

people on the edge between hard survival and simple joy. It is an

opportunity for the young men and women to sneak off into the forest.

(Camped for the night on the roadside, men and women squat

around their separate fires, heaps of pots illuminated by the flames.)

Where are you going?

“South to the big country.”

What will you do?

“Our life is like this:

Walk to eateat to walk

And a little rakshi in the evening

to warm us

And in the dark, to catch a silent girl

in the wild moonlit jungle”

There

are times for drinking and dancing. During the Holi festival, brown

skins turn day glow red and rainbow violet, as powder paint is thrown

at all passers by. The center of evening celebrations is a veiled,

silk-flashed dancer -- a female impersonator, who can dance freely

where the women cannot. Everybody watches, pouring beer and rakshi

into open mouths from wonderfully functional, phallus-spouted pots

-- the spouts crowned by a spiral bird's head. Later, men and women

do the old circle dances, after everybody is drunk enough to lose

their shyness. There

are times for drinking and dancing. During the Holi festival, brown

skins turn day glow red and rainbow violet, as powder paint is thrown

at all passers by. The center of evening celebrations is a veiled,

silk-flashed dancer -- a female impersonator, who can dance freely

where the women cannot. Everybody watches, pouring beer and rakshi

into open mouths from wonderfully functional, phallus-spouted pots

-- the spouts crowned by a spiral bird's head. Later, men and women

do the old circle dances, after everybody is drunk enough to lose

their shyness.

In February-March, all people who are able to walk a day come to

the festival of Shiva, held in the Lord of Deokhuri's mango grove.

The mood and structure are reminiscent of an American county fair,

with rows of bamboo booths roughly thatched with leafy branches,

where you can buy bangles and baubles, deep-fried sweets, tattoos,

rice and beans, have your fortune told, get your broken kerosene

lantern fixed, take your chances at ring-toss or the Wheel of Fortune.

The biggest attraction is a video show, which arrives hanging from

a procession of twenty coolies -- monitor, tape deck, speakers,

table, cash box, petrol and a generator that sputters its way through

a Hindi film. Three times.

After that, there is a stage show, with its cloth proscenium hung

from the trees and a car battery-powered sound system. After several

false starts, five seductive singers, dressed in iridescent saris,

swing their hips onto the stage. Their falsetto voices give them

away, but their energetic rendition and pranks keep the act interesting.

They are female impersonators by caste, a lineage that goes back

more generations than they can remember. Vaudeville is alive and

healthy in Deokhuri. The funky band goes on until dawn, with a rapt

audience of about one thousand people huddled close together in

their shawls, on the ground. The crowd is well behaved, probably

because the Lord and his sons carry big sticks and manage the crowd

easily -- with threats alone. Drunks are carried off and stuffed

into empty oil drums for the night. After several days of feasting,

potters return to work.

I

witnessed a major cultural transformation one year. After thousands

of years of round bottoms, the Tharus have started to slightly flatten

the base of their water pots. This occurred because cement floors

have become popular and you can no longer set your water jars directly

in a hollow in the earth. I witnessed another major change a few

years later, when the price of a water jar jumped from 25 to 40

Rupees -- 35 to 60 cents. This is a big difference to people who

make 70 Rupees a day. Firewood used to be collected freely by the

potters’ wives, who go into the nearby jungle every morning

with hatchets balanced on their heads, and return in the afternoon

with huge loads of firewood in their place. This year the government

set up guards at all the forest entrances. Their job is to collect

ten rupees tax on each load of wood. The only other option is itinerant

labor in Rajasthan, where many of the potters already go to harvest

crops seasonally. The effect may well be to permanently destroy

a way of life. I

witnessed a major cultural transformation one year. After thousands

of years of round bottoms, the Tharus have started to slightly flatten

the base of their water pots. This occurred because cement floors

have become popular and you can no longer set your water jars directly

in a hollow in the earth. I witnessed another major change a few

years later, when the price of a water jar jumped from 25 to 40

Rupees -- 35 to 60 cents. This is a big difference to people who

make 70 Rupees a day. Firewood used to be collected freely by the

potters’ wives, who go into the nearby jungle every morning

with hatchets balanced on their heads, and return in the afternoon

with huge loads of firewood in their place. This year the government

set up guards at all the forest entrances. Their job is to collect

ten rupees tax on each load of wood. The only other option is itinerant

labor in Rajasthan, where many of the potters already go to harvest

crops seasonally. The effect may well be to permanently destroy

a way of life.

“We don't have any wood to burn

There is a government now, we are told

There is a government come to squeeze us

The forest officers squeeze us

Obese and oily, they make us squat at their doorsteps

They all know how to squeeze us

How thin can we get?”

In Deokhuri, potters' wheels are made

from the same materials as houses

Bamboo, clay and cow dung

Vishnu’s spiral saligram stone

spinning on a sharpened stake

the potter

turns a linga

then he turns a yoni

form comes of this union...

You can hear the joy of it if you listen closely

The wheel turns slower and slower

and slowly

leans down to ground

“Just move slow...

We are not of your world.

We have animal eyes

trust comes slow

In every earth home

we keep the first clay man

and alert clay horses

in the shrine

in the corner.”

(You can’t have any idea

how fast

the modern devils are slipping in.

to eat up your first man

and the clay horses

and the magic hand prints on the mud wall)

(No one tells you

Coca Cola in the village store

made of sugar and status

will take all

your cash keep you in debt

to the Lord of Deokhuri

who may be benevolent

but gets his dues)

Revolution or not

Slavery persists even in dem-o-crassy

slavery humanized

by a certain sense of dignity in inequity

the long house where the men

smoke

and talk

and drink

and beat out the curve of their world

the resonant contour of great pots

empty songs waiting for the wind

to sound them

Jim Danisch

is an American studio potter and teacher. He spent nine years in

Thimi, Nepal, developing appropriate technology for producing glazed

earthenware. He trained Nepal potters and helped establish about

24 independent workshops. Danisch now lives and works in California.

He also conducts annual

ecotours to South Asia, some of them pottery-oriented.

More Articles

|