|

Larger than Life: The

Terracotta Sculptures of India

Article by Ron du Bois

Photos by Ron du

Bois, 1980, unless otherwise stated. ©

Massive terracotta horses have been built by Tamil villagers in

south India for thousands of years. Stephen Inglis states that "technically

they are the most ambitious achievements in clay found in India

and by any survey probably the largest hollow clay images to be

created anywhere" (1).

|

Massive terracotta Horse. Environs

of Puthur, Tamilnadu, South India. This fifty year old massive

clay image was fired on site. Because the fired surfaces are

porous a solution of oxides used as colorants are easily absorbed

and thus made durable. Fifty years have altered them only slightly.

Although the annual rains soak the porous clay, no harm results

because Tamilnadu never freezes. In other climates water penetrating

the clay could freeze and expand causing disintegration within

a season. |

|

Created from sacred temple ground, this horse

now stands purified by fire. No cracking or breakage due to

trapped air or moisture occurred. The non-ceramic decoration

of calcium carbonate and water penetrates the porous clay and

thus becomes durable. Rain and subsequent freezing weather could

spell the the disintegration of such massive clay images within

a season...but the temperature in Tamilnadu is always warm,

and thus the images stand for generations. |

The methods used to construct and to fire images nine to fifteen

feet or more in height are unique in ceramic history and of unusual

interest to clay specialists. They differ dramatically from the

images of horses and soldiers recently excavated in China, in that

they are larger than life-size and fired in situ. Not only is the

size impressive, but the proportions and embellishment are superb.

These works are created by a caste of hereditary potter/priests

who are products and heirs of an ancient tradition in which clay

and religion are inseparably linked.

|

| This massive terracotta Aiyanar horse image

was built around 1955. It is distinctive for its high relief

modeling. Much the original white wash is still extant. The

high relief elements are technically possible because copious

amounts of temper (rice straw) are mixed in the clay. |

Detail of relief modeling, 18 inches high, on

neck of ancient Aiyanar terracotta horse. Environs of Puthur,

near Chidambarum, Tamilnadu, India. |

Yet because the images are built in remote village shrines they

have been virtually ignored by scholars. As Inglis observes, "visitors

to Tamil Nadu may catch a glimpse of such images from the window

of a bus or train yet an interest once aroused is difficult to pursue.

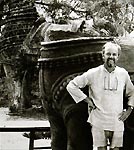

Katervil, master craftsman in clay, is known

throughout the region as a specialist for his skills in building

votive terracotta horse images as well as those built in cement.

He can make every type of utilitarian pottery as well. Heir

to an ancient tradition, his ancestors have practiced similar

skills for thousands of years. He is a "velar", or Tamil potter-priest.

Here he rests beneath the breast of of the horse on which he

has just completed the modeling of "Yallee", spirit guide, protector

of Aiyanar, able to see in all directions, able to see into

the future. Mystical skills enable him to guide the horse safely.

Katervil, master craftsman in clay, is known

throughout the region as a specialist for his skills in building

votive terracotta horse images as well as those built in cement.

He can make every type of utilitarian pottery as well. Heir

to an ancient tradition, his ancestors have practiced similar

skills for thousands of years. He is a "velar", or Tamil potter-priest.

Here he rests beneath the breast of of the horse on which he

has just completed the modeling of "Yallee", spirit guide, protector

of Aiyanar, able to see in all directions, able to see into

the future. Mystical skills enable him to guide the horse safely. |

Tamil people of the cities know little of them and for the ordinary

village people, work on such images involves skills and a sacred

ritual of which they have little knowledge. The work is almost never

seen in big towns or cities, sold in fairs, or otherwise displayed.

Although some attention has been given by scholars to the religious

complex in which they playa part, information about massive images

and the craftsmen who build them is not to be found in the literature

on south India" (2).

In May, 1980, as an Indo-American Fellow, I was able to observe

at first hand, in remote and abandoned village shrines, ancient

examples of these massive terracotta horses "with fiercely

noble heads standing ready to carry god or demon" (3).

As I looked at them, numerous questions came to mind: How old were

they? Who made them? What was their purpose? Were they still being

made? How could such huge clay images be fired? How could passages

of clay varying in thickness from two to sixteen inches be dried

and fired without mishap of any kind?

The answers to these questions would shed new light on the methods

used in the past by the Etruscans, the Chinese, and pre-Columbian

peoples to create such larger-than-life terracotta images. The

craftsmen who made them clearly used methods of construction and

firing outside the spectrum of Western ceramic skills and processes.

Few, if any clay specialists in the Western world would attempt

to build and fire on-site ceramic sculpture of such monumental scale.

Through the unfailing support of Ray Meeker and Deborah Smith of

the Golden Bridge Pottery in Pondicherry, I found some important

answers. Former students of Susan Peterson, they are the only American

potters successfully producing hand-thrown stoneware in India at

present.

Their plan of organization made the documentation possible. Intrigued

with the projected filming of the construction of an Aiyanar horse,

they offered me the use of their recently purchased jeep to search

for Aiyanar shrines and potters. The three of us, together with

Ray's assistant, Ratchagar, to serve as translator, set out on a

four-wheel drive field trip.

On a single day's outing, we sighted five Aiyanar shrines in the

outskirts of Chidambaram. Each of the sites held one or more terracotta

horses, each ten to twelve feet high constructed within the last

one hundred years. The surface decoration, in most cases, had weathered

away and the patina indicated considerable age. There was nothing

to indicate the date or the names of either the potters or donors.

Such facts were never recorded.

|

This ancient terra

cotta horse was built and fired on site some one hundred years

ago. It measures over ten feet in height. The high relief images

on the neck of the horse image were modeled of clay with an

admixture of straw. The images symbolize spirit attendants who

ride with Aiyanar at night to guard the village boundary. |

|

Detail of ancient horse (with

villager standing in front): The high relief images on the neck

of the horse were modeled with the solid clay mixture. They

symbolize spirit attendants who ride with Aiyanar at night to

guard the village boundary. |

|

About 100 years old,

four massive terra cotta horses constructed and fired on site

stand in a seemingly abandoned Aiyanar shrine. |

Were such horses still being built? Thanks to my friends' fluency

in Tamil we soon found a pottery community reputed to have horse-

building skills in the village of Puthur, sixteen kilometers from

Chidambaram. When we found the earth and thatch dwellings of the

potters, we discovered an Aiyanar shrine nearby complete with a

huge standing terracotta horse, which the potters claimed was more

than one hundred years old. Near the older form was a more recent

horse built of cement, a material that has now almost completely

replaced clay as the medium for shaping ritual images. To the west

stood a large cement image of Aiyanar and to the south, a shrine

housed a much smaller image flanked by two consorts. The shrine

is in active use. Each evening some forty villagers worship there,

the women touching their foreheads to the ground and the men prostrating

themselves completely.

The indigenous religious system, involving the belief in a male

deity, at once hero, protector, companion, and councilor, is Dravidian.

It predates by centuries the Aryan introduction of Hinduism with

its complex pantheon of deities in the second millennium B.C. During

the Middle Ages, in order to upgrade and legitimize Aiyanar through

association with mainline Hinduism, devotees evolved the story of

his birth as a son of Shiva and Vishnu (in the form of a beautiful

woman). Aiyanar helps on many important occasions in life -to choose

a bride or groom, to cure sickness, or to punish a wrongdoer. He

holds a metal sword in his hand on which devotees thrust paper messages

stating their various problems. Often the solutions are revealed

in dreams.

|

|

| S. Kalia Perumal was an important member of

the four man crew who constructed the horse. |

This potter's wife standing before the shrine

is in a state of trance. The closer presence of Aiyanar and

the forces of village deities stimulate states of possession.

For some their bodies temporarily become containers of the divine. |

We learned that the last large Aiyanar horse was commissioned

more than twenty years ago. But the potters assured us they still

knew how to build one. Would they do it? Would they accept a commission

from a non-Hindu - a foreigner? I was impressed with the potters

and had a genuine sympathy and liking for Aiyanar and his shrines.

Unlike Hindu temples, his shrines were always located in secluded

country areas in which trees were a necessary and auspicious component.

They were restrained-the sculptural quality of the clay or cement

images was stable and impressive. Perhaps the potters were moved

by my positive attitude and interest in Aiyanar; at any rate, they

decided to accept the commission. They agreed to build a horse nine

feet high in twenty days; it was to be situated next to the existing

horses. They quoted a price of 500 rupees. After haggling, they

reduced the figure to 400 rupees- ($48.00) - a good price by Indian

standards but by Western standards extremely low when one considers

that four or five men would work for twenty days to complete the

commission.

Day One:

They knew their business. On Monday, May 26, 1980, a puja (ritual)

was held to ensure the success of the project. To consecrate the

ground on which the horse was to be built, the potters encircled

the area using the blood streaming from the neck of a decapitated

rooster. Coconut halves were placed to each side of the area.

Liquor, an essential ritualistic ingredient, was present although

Tamil Nadu is a "dry" state. Technically, liquor is

illegal but this was "home brew," which escaped official

scrutiny. Food offerings to Aiyanar completed the ritual. Secure

in the assurance that Aiyanar was now companion to the project,

the potters began construction.

The preparation of the clay had taken place the day before. A circular

earth pit about four feet in diameter served as a mixing trough.

One part sedimentary earthenware is mixed with one part earthenware

topsoil. Although fine-grained, it contains silt. To this enough

water is added to produce a medium-viscosity slurry. The potters

knew this clay would fail as a medium for building large sculpture.

Large quantities of non-plastic ingredients are essential to prevent

shrinkage and hence cracking, as well as to permit thick passages

of clay. The non-plastic ingredients consist of three parts rice

hulls and approximately one part (by volume) of three-to-four-inch

lengths of rice straw. The potters added this to the earthenware

slurry and mixed it by foot to produce a medium soft mixture possessing

all the qualities of a "castable."

|

| First Day of Construction. Aiyanar

Shrine, Puthur, Tamilnadu, South India, 1980. Holes 12"

deep and 12" wide were excavated in the ground possible

to relieve air pressure during firing. Katervil applies a heavy

coil of clay with an admixture of rice straw to form the "hooves",

the first stage in the construction of a massive terracotta

horse. These constitute the first procedures in the construction

of a massive Aiyanar horse image. When completed it will stand

ten feet high. In the background stands an ancient terracotta

horse said to be 100 years old. |

Large coils of this material were used to form rings around previously

inscribed twelve-inch circles on the ground marking the four "hoofs"

of the horse. A second coil of clay joined to the initial ring

extended the diameter to sixteen inches. Four of these clay rings

were formed to establish the four "hoofs" of the horse's

legs. This accomplished, a potter, using a metal excavating tool,

dug holes approximately twelve inches deep inside each ring of

clay. A potter set a wooden pole about six feet high inside one

hole and held it while a colleague quickly filled the entire hole

with clay thus supporting the pole in a vertical position. In

a similar fashion, vertical poles were set in the three remaining

holes. Each wooden pole, therefore, was supported by a solid mass

of clay mixture about sixteen inches across and twelve inches

deep. Without the use of rice hulls and straw such passages would

shrink and crack.

These ingredients are the major part of the mixture by volume

and are essential to this type of monumental clay construction.

The last part to be constructed was a clay base for the central

rectangular support, 24" x 24". This completed the first

day's work. Nothing further could be done until the moist clay

mixture stiffened.

The potters spent their time in the afternoon preparing ropes

made of rice straw. Wrapped around the wooden uprights these ropes

create a compressible internal support system for the application

of about a four-inch wall of clay thereby eliminating any possibility

of the clay cracking as it dries and contracts.

Woman Creating a Colam. Colams are ritual diagrams

or drawings that welcome the dawn, or gods to their festivals.

They illustrate the power of geometricity to create a force

field or maze by which untoward forces are confused and thus

kept at bay. Mostly women create the geometric designs with

rice flour. Colams celebrate the impermanence of art and art

as an essential aspect of daily devotion. Their beauty of form

and endless variety are at once decoration and ritual.

Woman Creating a Colam. Colams are ritual diagrams

or drawings that welcome the dawn, or gods to their festivals.

They illustrate the power of geometricity to create a force

field or maze by which untoward forces are confused and thus

kept at bay. Mostly women create the geometric designs with

rice flour. Colams celebrate the impermanence of art and art

as an essential aspect of daily devotion. Their beauty of form

and endless variety are at once decoration and ritual. |

Day Two:

On the morning of the second day of construction the potters completed

the task of winding the straw ropes around the four wooden uprights.

They then applied a four-inch wall of clay so that four large tubes

about 40 inches tall were formed, each serving as a metaphorical

leg. Next, four vertical uprights were fixed at the inside comer

of the base of the central rectangular support previously completed.

Straw ropes were wound around them to create an armature for a thick

application of clay. The potters worked surely and quickly in spite

of a 112 degree Fahrenheit temperature. Descendants of generations

of clay craftsmen, they have learned the skills from childhood and

are concerned only with the work at hand, In the afternoon they

completed the front and rear legs and the central rectangular support.

The front legs now stood as a single unit 44 inches high, 38 inches

wide, and 17 inches across, measured at the top center. By fixing

wooden supports to the wooden uprights, the potters created a horizontal

passage of clay that bridged the two front and rear legs. The clay

mixture was laid over and under these supports to create a level

horizontal surface. This completed, nothing more could be done until

the horizontal passages of clay stiffened.

|

|

| The legs of the horse are constructed

of four wooden poles, rice straw, and rope. Clay slurry is applied

over all. The potters bridged the front and rear legs. |

The two front legs are now stiffened.

Katervil uses a wooden support covered with rice straw to form

a compressible internal support. As the thick clay passages

dry and shrink the internal straw support compresses to prevent

cracking. |

Day Three:

On the morning of the third day, additional wood supports were placed

horizontally to connect the front legs to the central support and.

then to the rear legs' unit. The potters molded the horse's under-belly

by laying "gobs" of the clay directly on the wood supports

(both above and underneath); this process produced a slab four inches

thick, seven feet, ten inches long, and thirty-four inches wide!

Such a feat was possible only because of the wooden internal support

system.

|

| Third Day of Construction. To bridge the pillars

forming the legs and the central support unit clay was applied

over horizontal lengths of wood wrapped with rice straw held

in place with rope. To prevent cracking rice straw is essential

as an internal support because it compresses as the clay dries

and shrinks. Four wooden poles wound with rope and rice straw

formed an internal support on which clay was applied to form

the central support unit. The height of all three units is three

feet, eight inches. |

After the burning rays of the sun had stiffened the slab, the

potters next added coils of clay to form the curve of the belly,

a process which added seven inches to the height. They tapered

the edge of the final coil. When the clay was stiff, the diagonal

slant provided a broader surface and hence a good join for the

next application of clay.

Day Four: In the afternoon the potters, using

thick gobs of the basic clay mixture, modeled the figure of the

guardian (or groom) of Aiyanar's horse directly on the surface of

the central support form.

The modeling of the image of Aiyanar's groom

starts with massive gobs of the clay mixture and will be finished

with a levigated slip mixed with sand. This older, mustached

image symbolizes the neither aspects of the deity's nature.

Katervil's deft fingers bring the image to life and vitality.

Potter-priest and master clay craftsman of both utilitarian

and sculptural forms, he models the groom of Aiyanar with thick

gobs of clay on the central support of a massive Aiyanar horse

image. He, poses beside the completed form which took two hours

to complete. |

An older, moustached image on the opposite

side of the central support column symbolizes the neither

aspects of Aiyanar's nature...dark and problematic. The smooth,

ever youthful groom seen here symbolizes his divine nature.

An older, moustached image on the opposite

side of the central support column symbolizes the neither

aspects of Aiyanar's nature...dark and problematic. The smooth,

ever youthful groom seen here symbolizes his divine nature. |

Day Six: lengths of bamboo are placed inside

the figure to complement exterior supports.

Katervil

laid wooden sticks horizontally to connect the front legs, central

support column and rear legs. He applied the clay mixture around

these supports to form a horizontal slab, thirty-four inches

wide by seven feet ten inches long. Katervil

laid wooden sticks horizontally to connect the front legs, central

support column and rear legs. He applied the clay mixture around

these supports to form a horizontal slab, thirty-four inches

wide by seven feet ten inches long. |

Horizontal

lengths of bamboo (one visible on the top interior wall) are used

to support the walls and to reduce accidental damage by children

or cows. Because the shrine is sacrosanct there is no intentional

vandalism. Horizontal

lengths of bamboo (one visible on the top interior wall) are used

to support the walls and to reduce accidental damage by children

or cows. Because the shrine is sacrosanct there is no intentional

vandalism.

Some of the passages were four inches thick, attesting

to the non-plastic nature of the basic clay mixture. An application

of pure clay over the coarse basic clay followed, and detailing

was done with fingers and a wooden modeling tool. The modeling skills

are of a high order and result in a figure with remarkable spring

and incipient energy.

|

| Katervil and two assistants are shown in process

of hand modeling in high relief the bells associated with Hindu

and some village deities. In the modeling of the jewels, bells,

and other decorative details, the intersection of the potter's

skills and the common elements of Indian design are seen. The

decorative clay bands are identical to those applied to mounts

on great temples by stone carvers, and to processional mounts

and decorative architecture by wood workers...the skills of

the garland and harness maker all flow behind the potter's skill. |

|

|

| Ron du Bois and 16mm film

camera. Aiyanar Shrine, Puthur, Tamilnadu, South India, 1980.

An attendant holds an umbrella over the camera to protect

it from the blistering sun. At 114 degrees F., the camera

could become burning hot and the canister of film inside ruined.

A homemade evaporative cooler was devised to store and save

the 16mm film canisters from damage. They were kept dry by

placing them a lidded plastic container. This in turn was

placed within a large terracotta vessel. Sand poured around

the plastic storage container was then watered to cool the

film by evaporation.

|

7th Day of Construction. Ron

du Bois, Indo American Fellow, with massive terracotta horse

in process of construction. The final height of the massive

sculpture was nine feet, ten inches. An ancient terracotta

horse built over 100 years ago is seen in the background. Photo

by Ray Meeker, 1980. |

The basic clay mixture is similar to what, in the West, is considered

to be a "castable" -a clay body suitable for bricks, refractory

linings, or kiln construction but rarely considered as suitable

for ceramic sculpture. Again, to the Western craftsman, a kiln for

firing ceramic sculpture would appear essential. As a result he

limits himself to forms that can be lifted and moved into a kiln.

The idea of firing "in situ" at the site of construction

rather than in a studio/workshop has never been the practice. Permanent

kilns, plumbing and wiring for gas, oil, or electricity have all

been part of the Western paradigm - yet the Etruscans, pre-Columbians,

Africans, and the potter-priests of India as well all constructed

temporary clay walls for on-site firing of monumental ceramic forms.

|

|

| Only a portion of the back form is closed.

To form the tail a wire serves to support solid masses of the

soft clay mixture. |

The back is then completely closed by a massive

clay slab supported by shards placed on sticks within the horse. |

|

A red slip or sigillatta

is applied to seal and to smooth the course surface. The length

of the horse is thirteen hands, the height of both torso and

legs is each four hands. The length of the still to be built

neck will be four and one-half hands. These proportions passed

from father to son may be adjusted only slightly depending on

the judgment of the team leader. |

|

The face on the breast of the

horse is Yallee...it's fierce gaze guides the god on his nightly

rides. Developed over the ages this image is shared with the

Hindu art of large towns and cities, but is now part of the

village modeling tradition. Able to see in all directions, able

to see into the

future. Because of this he guides the horse safely |

Day Nine: The entire neck, saddle and tail

are complete.

|

Right: To prevent sagging a wooden

brace was used to support the mass of soft clay used to form

the head. It is now the 10th morning and the clay has stiffened

overnight. The potters work to complete the final details -

eyes, ears, bridle, mouth, teeth and tongue. |

|

Day Twelve: Moist earth chopped from an adjacent

drainage ditch was carried by baskets to the construction site to

form the wall for an "open Field" firing. At a height of 18 inches

it is left to stiffen before adding more earth. A 10 inch wall thickness

is maintained until the final height of five feet is attained.

Right: The image peeks out, almost completely

covered by earth, clay vessels, wood, dung, and straw. As the

wall grows around the image, the image of the beast inside is

felt. The horse remains an almost mythical creature in South

India ...imported in small numbers for the ancient kings, and

now transformed from clay into the mount of a god.

A slurry made from ditch mud and water is carried

in baskets and poured over the straw...five men take only twenty

minutes to spread the thick slip over the entire surface and

to overlap the clay wall. The fire is started through a firehole

igniting the layers of straw, dung and wood that surround and

support the figure. |

Day Fourteen: The firing is completed within

three hours.

The potters brought the project to a conclusion with

a final puja (religious ceremony) and a "bringing to life"

of the successfully fired and decorated horse. It is hoped that

these notes and photographs will benefit Western craftsmen and serve

to enhance internationally the most impressive but little-known

skills of Indian potters.

Download a one minute video of the pre-construction

puja ceremony. Warning - this video contains footage of an animal

sacrifice that may be distressing to some viewers. Download

video (6.5 Mb, Quicktime movie).

Footnotes:

- 1-2 Stephen R. Inglis, "Night Riders: Massive Temple Figures

of Rural Tamil Nadu, in V. Vijayavenugopala (ed.) A Festschrift

for Prof. M. Shanmugam Pillai, Madurai University Press, 1980.

- 3 Stella Kramrisch, Unknown India: Ritual Art in Tribe and Village.

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Ron du Bois, an emeritus professor of art, taught ceramics and studio

art at Oklahoma State University, USA. He was Fulbright professor

to Korea in 1973-74, where he taught ceramics at three Korean universities.

His award winning documentary, The Working Processes of the Korean

Folk Potter, was filmed at that time. In 1979-80, du Bois traveled

extensively in India as a 1979-80 Indo-American fellow to research

and document the work of Indian potters. Among other projects he

filmed the entire construction of perhaps the last massive terracotta horse to be built in India. The documentary, "The Working

Processes of the Potters of India: Massive terracotta Horse Construction"

was completed under the auspices of the National Endowment for the

Humanities and deals with the subject matter of this article. In

1987, du Bois was awarded a 10 month Fulbright Senior Research Scholar

grant, African Regional Research program, to research and document

Nigerian potters. For information on his POTTERS OF THE WORLD FILM/VIDEO

SERIES contact: Ron du Bois, Professor Emeritus, http://www.angelfire.com/ok2/dubois,

612 S. Kings St., Stillwater, OK 74074, (405) 377-2524, email: duboisr@sbcglobal.net,

fax: 1-405-372-5023

Also by Ron du Bois: A Saga of Synchronicity

-

Making a Film Documentary on African Ceramics

More Articles

|