Jingdezhen

classical porcelain is unlike any other clay. Westerners have

described its properties as like throwing cottage cheese.

The first porcelain of late 10th century Song Dynasty consisted

of one ingredient, chinastone felspar, petunze in the local

dialect. The rock was ground into a paste by water-powered

hammer mills, a practice still in use today. The restrictions

of throwing wet powdered stone resulted in the intimate wares

of Song and Yuan dynasties. Kaolin clay, gaolin, was discovered

around 500 years ago during the Ming Dynasty in the mountain

village of Gaolin. This addition of white gaolin clay to the

petunze gave a structure to the porcelain and made possible

the throwing of large forms, both as complete pieces and in

the sectional cylinders of the body-height vases.

Jingdezhen

classical porcelain is unlike any other clay. Westerners have

described its properties as like throwing cottage cheese.

The first porcelain of late 10th century Song Dynasty consisted

of one ingredient, chinastone felspar, petunze in the local

dialect. The rock was ground into a paste by water-powered

hammer mills, a practice still in use today. The restrictions

of throwing wet powdered stone resulted in the intimate wares

of Song and Yuan dynasties. Kaolin clay, gaolin, was discovered

around 500 years ago during the Ming Dynasty in the mountain

village of Gaolin. This addition of white gaolin clay to the

petunze gave a structure to the porcelain and made possible

the throwing of large forms, both as complete pieces and in

the sectional cylinders of the body-height vases.

Since

the Ming period, the composition of the porcelain body has

remained 60 per cent chinastone and 40 per cent kaolin. Both

materials were traditionally made into brick shapes and mixed

together. Before the invention of the pugmill, craftsmen would

wedge a large mass of clay with their feet into a circular

mound. Now it is pugged and then lightly rolled towards the

body. Containing no ball clays and thus having little plasticity,

classical Jingdezhen porcelain is an adventure to throw. The

general rule is to throw thick walled pieces and, when thoroughly

dry, trim both the inside and outside to desired thickness.

As much as half the body will be trimmed away. The wheel is

run on a large and powerful electric motor with pulleys. An

old-fashioned lever that clicks into notches regulates the

speed, much like the old farm tractors. Thick bats, more than

one metre in diameter, are centred on the wheel head and stay

in place by the sheer weight of the clay.

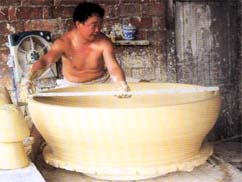

Since

the Ming period, the composition of the porcelain body has

remained 60 per cent chinastone and 40 per cent kaolin. Both

materials were traditionally made into brick shapes and mixed

together. Before the invention of the pugmill, craftsmen would

wedge a large mass of clay with their feet into a circular

mound. Now it is pugged and then lightly rolled towards the

body. Containing no ball clays and thus having little plasticity,

classical Jingdezhen porcelain is an adventure to throw. The

general rule is to throw thick walled pieces and, when thoroughly

dry, trim both the inside and outside to desired thickness.

As much as half the body will be trimmed away. The wheel is

run on a large and powerful electric motor with pulleys. An

old-fashioned lever that clicks into notches regulates the

speed, much like the old farm tractors. Thick bats, more than

one metre in diameter, are centred on the wheel head and stay

in place by the sheer weight of the clay.

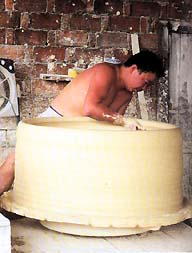

The next step is to get a dozen or more of

the 10 kilo porcelain balls on to the wheel. The growing mound

is centred one ball at a time until a sufficient mass is attained.

Initial centring requires the help of an assistant grasping

the hands of the master thrower and forcing his energies through

the master’s hands to centre the clay. At some studios

two assistants steady the master’s hands for centring

and opening. The centred clay is then opened and the bottom

is quickly widened to its desired measure. The walls are raised

progressively and then shaped. An assistant’s hands

are used in the throwing until the final shape is near. The

last shaping is completed by the master alone until the form

reaches 1.5 m in diameter. The apparent simplicity and ease

belie a master’s touch with a difficult material. The

rim is carefully measured with a stick. Many shapes are parts

of a two or three piece finished form.

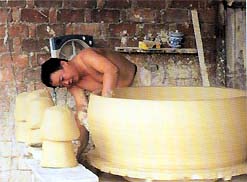

Sections are assembled after the pieces have

become bone dry in the sun and each section has been rough

trimmed. A slurry of pancake batter consistency is made with

the trimmings from the specific pieces to be joined. This

is poured on to the rim of the bottom piece and the top section

is lowered and centred. Within 10 seconds the trimmer begins

to shave the assembled form to a final shape. The tools are

kept razor sharp. It takes four men to haul away the porcelain

form on a wooden platform with handles and take it out into

the sun to dry. If it does not crack here it will make it

through the firing. Attempting to trim Jingdezhen porcelain

before it is dry is folly because the tools gouge out chunks

of clay. The tools and the process must follow the nature

of the material. A final soaking of the surface with a thick

round brush dipped in water reveals any imperfections such

air bubbles which must be removed.

Cobalt

blue qinghua decoration is frequently brushed on to to the

greenware by skilled painters. A clear glaze is applied with

spray gun – formerly by spray can and strong lungs.

All Jingdezhen wares are once-fired at 1300–1330°C

in propane gas kilns – the old coal-fired kilns are

being phased out. Enamels or gold lustres can be added with

an additional firing at 800°C.

Cobalt

blue qinghua decoration is frequently brushed on to to the

greenware by skilled painters. A clear glaze is applied with

spray gun – formerly by spray can and strong lungs.

All Jingdezhen wares are once-fired at 1300–1330°C

in propane gas kilns – the old coal-fired kilns are

being phased out. Enamels or gold lustres can be added with

an additional firing at 800°C.

Jingdezhen is the home of nine of the 26 Masters of Art and

Craft of China, the highest national accolade. This title

is generally reserved for the decorators. The unsung craftsmen

throwers are hidden away in factories and one stumbles upon

them to watch in awe at their tremendous skill and humbleness.

During the events of the Jingdezhen 1000 Years Celebration

of Porcelain taking place in 2004 and 2005, visitors will

be rewarded by a guided tour to the factory studios to learn

the secrets of classical porcelain techniques, including the

virtuosity of the master throwers.