| Moments

in Black and White

Maiju Altpere-Woodhead discusses idea, process and materialisation.

Article origianlly published in

Ceramics

Technical, Issue #20.

Crossing

borders and making use of techniques from other mediums is by no

means new to ceramics. This practice of borrowing has for centuries

allowed makers to enrich their visual and technical vocabulary and

achieve new and exciting aesthetic results. Whether used for commercial

production or individual artistic expression, various methods of

classical printmaking have been part of ceramics since the advent

of printing itself. Crossing

borders and making use of techniques from other mediums is by no

means new to ceramics. This practice of borrowing has for centuries

allowed makers to enrich their visual and technical vocabulary and

achieve new and exciting aesthetic results. Whether used for commercial

production or individual artistic expression, various methods of

classical printmaking have been part of ceramics since the advent

of printing itself.

I was first introduced to the possibilities of ceramic mono-printing

through the work of Norwegian artist Ole Lislerud, who has used

the technique to create monumental architectural artworks such as

the central portal in the Oslo Courthouse and the façade

of the Performing Arts Centre in Ålesund, Norway. While impressive

in scale and technical mastery, it is the successful match between

concept, aesthetic objectives and a technical process that has inspired

me most about Lislerud’s work. During a student exchange to

the National College of Art and Design in Oslo in 1997, I had an

opportunity to study under his guidance and, among other things,

learn the basic principles of this method. However, it was only

in 2004, when I started working on the Moments in Black and White

series and exploring issues around personal emotional responses

to various environments, that I returned to the mono-printing technique.

Ever since moving to Australia from Estonia in the Northern Hemisphere

in 1992, I have been intrigued by the ways recollections of other

places influence and inform one’s relationship with present

surrounds. As new impressions are embedded into the existing web

of sentiment and experience, the boundaries between past and present,

old and new become blurred. Familiarity is found or formed through

elusive associations with occurrences from the past and these associations

themselves change from context to context. Likewise, memories and

meanings are created and re-created, arranged and re-arranged in

a process with no finite beginning or end nor a set hierarchical

order.

The Moments in Black and White series is a materialised reflection

of personal meaning, making and memory processes. It consists of

an open-ended number of small cylindrical mono-printed porcelain

forms that can be assembled randomly or selectively, separating

and banding them together, swapping from group to group. I have

limited myself to a monochromatic black and white colour scheme

and a basic cylindrical form. Starting with these basics has allowed

me to gradually develop more complexity and diversity both in terms

of form and surface imagery while maintaining a sense of coherence

between individual pieces. While the diameter of the cylinders remains

more or less constant, their height and rims vary, creating movement

and visual rhythm in different assemblages. Likewise, the colour-palette

accommodates a wide range of subtle ‘colour greys’ that

result from both the make up of the coloured slips and variations

in firing atmosphere.

The method of mono-printing that I use combines elements of classical

intaglio printing and monotype. This combination has allowed me

to express the constant change and unpredictability of memories

as they move in and out of our consciousness, as well as involve

the element of familiarity. On the one hand it utilises the spontaneous

painterly qualities of monotype and its uniqueness among other printing

techniques as a means of producing only one print of an image. On

the other hand, it borrows from the classical intaglio techniques

in which the imagery is incised into the printing plate, resulting

in a print that replicates the graphic markings or textures of the

plate and has the potential of seriality.

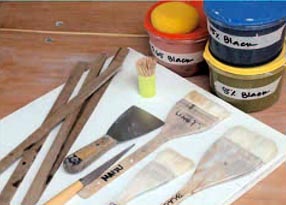

For printing I use a number of plaster slabs that have been cast

on to glass or smooth melamine surface. The slabs are all the same

size (40 x 40 cm) and 2 cm thick. First I cover the even surface

of the slabs with incised linear designs. Any sharp metal implements

such as used fine ballpoint pens, the tip of a knife or saw blades

can be used for carving. Wiping the slab with a damp sponge changes

the definition and quality of the carved lines and makes the carving

easier as the plaster softens and is more responsive. Because of

the superbly sensitive nature of cast plaster, every alteration

to it becomes visible. However, as plaster is also soft, markings

will lose definition and even disappear with subsequent prints.

These clashing qualities make working with plaster slabs both challenging

and fascinating and I often keep using and rotating the same plaster

plates over and over again, sometimes way beyond their practical

use. Working the plates by altering or adding new markings to the

already existing and fading ones enables me to make a record of

change, as images appear, metamorphose and gradually disappear while

all along retaining traces of their former identity. Once the printed

images are exposed to the irreversibly transformative force of fire,

this record of change becomes permanent. After carving, the surface

needs to be cleaned thoroughly with a dry brush and damp sponge

to remove any fine plaster particles before applying clay slip.

I always discard the first cast from every new slab as it may contain

impurities such as soap scum or plaster dust, and let the plaster

dry completely. Before applying the first layer of clay slip, the

carved slab is wiped briefly with a damp sponge. Then, using a wide

soft flat brush, the entire surface of the slab is evenly covered

with a coloured slip. I usually work with a number of brushes and

keep those that I use for darker colours separate from the ones

for lighter colours. As soon as the slip has lost its sheen it can

be scraped off using a wide straight blade, leaving slip only in

the carved lines. Over this matrix of graphic markings I start applying

layers of coloured slips, scraping parts of them back much like

in classical monotype. It is a spontaneous and rather intuitive

process as I keep covering previous layers while working on the

composition from front to back. As the surface imagery is built

up layer by layer it also becomes an integral structural component

for the resulting forms, being embedded in their walls.

Once the composition is finished, four 2 cm wide and 3-4 mm thick

masonite strips are placed along the edges of the plaster slab.

These will hold the liquid slip in place while the backing slab

is being cast. To cast the backing slab I measure a required amount

of stirred casting slip into a pouring jug. While tilting the slab

with one hand I pour the slip on to the slab, starting from the

centre top and moving from side to side. Tilting the slab forces

the slip flow downwards and avoids ‘casting lines’ which

may cause cracking. Once the slab is covered to desired thickness,

it is placed on a level surface and the slip left to set. As soon

as the cast slip loses its sheen, the masonite strips are removed

and the slightly raised edges trimmed with a sharp knife. At this

point I need to work swiftly as the cast slab will lose plasticity

quickly and become unsuitable for further shaping. To release the

printed sheet, I first carefully lift the corners by easing them

from plaster with a thin flat blade. Holding gently but firmly from

two top corners, the cast porcelain slab is turned over on to a

clean board and the printed image revealed. While the entire process

is not complex there is always an element of accident and surprise

that, together with the changes that occur during firing, can alter

the original idea dramatically.

After removing the printed slab from the plaster, it is cut into

segments and shaped into cylinders of various heights. This fragmentation

of the printed image creates an aspect of continuation between individual

pieces and a sense of movement in the groupings of otherwise static

objects. The sense of extension is emphasised by the fact that I

reuse and rotate the plaster slabs and while each printed image

is different they share certain visual elements. The combination

of a painterly imagery superimposed with textured and defined graphic

markings resulting from this mono-printing technique allows for

the construction of complex yet undefined visual spaces with permeable

layered depth. While the surfaces of the printed forms in the Moments

in Black and White series can be read as a reference to landscape

or natural environment, it is not intended as literal representation

of any particular location. Rather, it is to act as a trigger for

various abstract associations with natural phenomena and cultural

expressions. The tactile contrast between the slightly raised relief

of the lines against the smooth satiny surface invites the viewer

to pick up the pieces, feel and examine them closely and then reposition

them, creating different compositions. It is through these personal

responses that the work gains new meanings, taking the original

idea to another level.

Maiju Altpere-Woodhead is a potter working in Canberra,

ACT. She has won awards for her work and exhibits regularly. Photographs

of finished work by Stuart Hay – ANU Photography. Demonstration

photographs by Britt Woodhead. The development of this article has

been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia

Council, its arts funding and advisory body, as part of its Craft-in-site

initiative managed by Craft ACT.

Article © Ceramics

Art & Perception/Ceramics Technical.

More Articles

|